If history teaches anything about the causes of revolution—and history does not teach much, but still teaches considerably more than social-science theories—it is that a disintegration of political systems precedes revolutions, that the telling symptom of disintegration is a progressive erosion of government authority, and that this erosion is caused by the government’s inability to function properly, from which spring the citizens’ doubts about its legitimacy.

Hannah Arendt, “Civil Disobedience”

November 2013 seemed like an unlikely time for another Ukrainian revolution.

Nine years had passed since the Orange Revolution, a massive wave of popular protests against a massively rigged presidential election, achieved inspiring success to be almost immediately followed by bitter disappointment. In 2004, hundreds of thousands of protesters filled Kyiv’s central Independence Square, Maidan Nezalezhnosti, drowning the city in orange, the presidential campaign color of Viktor Yushchenko, a liberal and pro-Western candidate, whose rightful presidency was stolen by blatant election fraud.

The Orange Revolution’s demand was ultimately granted, and the rerun of the stolen election brought Yushchenko to power. But the Orange coalition quickly fractured and in 2010, Yushchenko’s 2004 rival, the thuggish Russia-friendly Viktor Yanukovych, was fairly and squarely elected president. The Ukrainian government was now firmly captured by shamelessly self-enriching oligarchic interests with unambiguous ties to Russia. Staging another nationwide collective action seemed like an effort the disenchanted and resigned nation could not muster.

A sense of agency

In November 2004, I was in my kitchen in a small town in southern Maine, making apple sauce, when NPR reported about the swelling numbers on the Maidan. I dropped the apple sauce and called a friend in Washington, DC, another Ukrainian from Lviv. In a week we were on a flight to Kyiv, me with my nine-month-old daughter and she with her two toddlers. Our mothers met us in Kyiv to pick up our kids and take them to Lviv. We stayed on the Maidan.

Why were we there? What was the use of flying from the United States to stand daily on the Maidan, for a month, in December cold, where among thousands one person made no difference? For one, while the political aims were serious and legitimate, the Orange Revolution transpired in an atmosphere of jubilation. Thousands in orange paraphernalia filled the Maidan, many traveling from other cities or returning from abroad, like I did. For me, it proved the ultimate reunion with friends I hadn’t seen in years. A stage was promptly erected, and Ukraine’s best performers took turns entertaining and rallying the crowds. The Orange Revolution was the Woodstock for democracy.

To be there was to partake in a sense of collective agency, to contribute to safeguarding Ukraine’s fragile democracy, which was not only our right but our obligation.

But the real reason we were on the Maidan was that we believed each one of us could make a difference. In fact, to be there was to partake in a sense of collective agency, to contribute to safeguarding Ukraine’s fragile democracy, which was not only our right but our obligation.

For many Ukrainians of my generation, the belief that concerted collective action can bring about political change was probably a function of coming of age at the time of the great transformation of the late 1980s and the early 1990s. We were not passive observers of history, we were its agents of change, children of the agents of change, who found cracks in the seemingly impregnable Soviet monolith and chipped away at it from within.

It was the preceding generations of dissidents who chose, following Vaclav Havel, to do the only thing that gives power to the powerless, “to live within the truth,” and paid for this choice with persecution and imprisonment. It was the persistent, irradicable whisper of our parents and grandparents in our ears, transmitting chapters of national memory, history, and customs, omitted, distorted, and prohibited by the Soviet officialdom. It was our irreverent mockery of the geriatric Communist party bosses. It was the vast and visceral indignation over the 1986 Chernobyl debacle. It was the students’ hunger strike in October 1990 on the Maidan (then the October Square), the first Ukrainian revolution, the Revolution on Granite, against the signature of the new Union Treaty, a doomed endeavor to rejuvenate the ailing Soviet empire and keep Ukraine tethered to Moscow.

Succumbing to a thousand cuts, the crusty old Soviet edifice, built on lies and coercion, finally came crumbling down in 1991, and we knew that it was we, the ordinary people of Ukraine—joining hands with the ordinary people of East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Baltic states—who did our part in its undoing, no matter how much credit Western capitals claimed.

The first post-Soviet years were lean but filled with hope, if only because we were young, standing on the threshold of adulthood, with opportunities our parents could never have dreamed of. We were told that we were Ukraine’s future; that they, our parents’ generation, were handicapped by the permanent damage inflicted upon them by the Soviet system, the Soviet mentality. They won Ukraine its independence, but they could take it no further, and it was we who now had the torch of responsibility to guide Ukraine toward democracy, prosperity, and the rule of law—all good things that, with time, would come to be captured by a single concept: “Europe.”

Ukraine’s economic ruin and idealism of the early 1990s in time gave way to increased prosperity but also to the sinister consequences of a mismanaged transition. The continued reign of the Soviet-era apparatchiks, the fire-sale of state assets against an antiquated and unenforceable legal code, and the serious difficulty of transforming an inefficient state-run economy into a market-driven but fair system proved a perfect primordial soup to spawn a handful of fantastically rich people, the oligarchs, some controlling enormous stakes in the national economy—metallurgy, energy, banking, media. By the 2000s, having all but captured the economy, the oligarchs were jostling to capture the state.

In that, the fate of post-Soviet Ukraine was not dissimilar to the fate of post-Soviet Russia: a mutant system grown out of an unreformed Soviet legacy and the most ruthless exigencies of unchecked capitalism. Russia in the 2000s took a turn toward order and rule, not of law but of one man, Vladimir Putin, a former KGB colonel, who rose out of obscurity to the apex of power where he would remain to this day. The Russian system produced Putin and Putin proceeded to shape the Russian system by building a rigid neo-feudal vertical of power that turned oligarchs into state vassals and a managed democracy that preserved the ritual of elections while snuffing out all space for competitive deliberative politics. But that would become clear later. In the early 2000s, the West hailed Putin as a pragmatist and an architect of stability and order badly needed in a Russia ravaged by the democratic chaos of the 1990s.

Leonid Kuchma, March 17, 2004. REUTERS/Sergei Karpukhin.

Viktor Yushchenko, April 4 2005. Olivier Douliery/ABACA.

Yulia Tymoshenko, January 15, 2005. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich.

Viktor Yanukovych, September 30, 2007. REUTERS/Grigory Dukor.

Danse macabre

Ukrainian politics, by contrast, remained manifestly disorderly and outright messy, sending Western observers into eye-rolling bouts of “Ukraine fatigue.” Indeed, had it not been for the millions of lives and livelihoods it impacted, Ukrainian politics was the stuff of a tragicomic political soap opera.

The cast alone!

There was Ukraine’s outgoing second president, Leonid Kuchma, a former Soviet missile factory director, who took over from Ukraine’s first president, Leonid Kravchuk, a former Communist party ideologue, and who presided over the rise of the oligarchs, one of whom married his daughter, as well as over the infamous murder of journalist Georgiy Gongadze, who investigated Kuchma’s ties to the oligarchs.

There was Viktor Yanukovych, Kuchma’s last prime minister and heir-elect, who in his youth was a racketeer in the coal-mining region of Donbas and had served time for robbery and assault, before rising to regional and then national politics.

There was his running opponent, the pro-Western Viktor Yushchenko, a former central banker and a one-time prime minister in Kuchma’s government, whose father had survived Auschwitz and who, a month before the elections, would himself barely survive a mysterious poisoning with dioxin that left his handsome face permanently pockmarked.

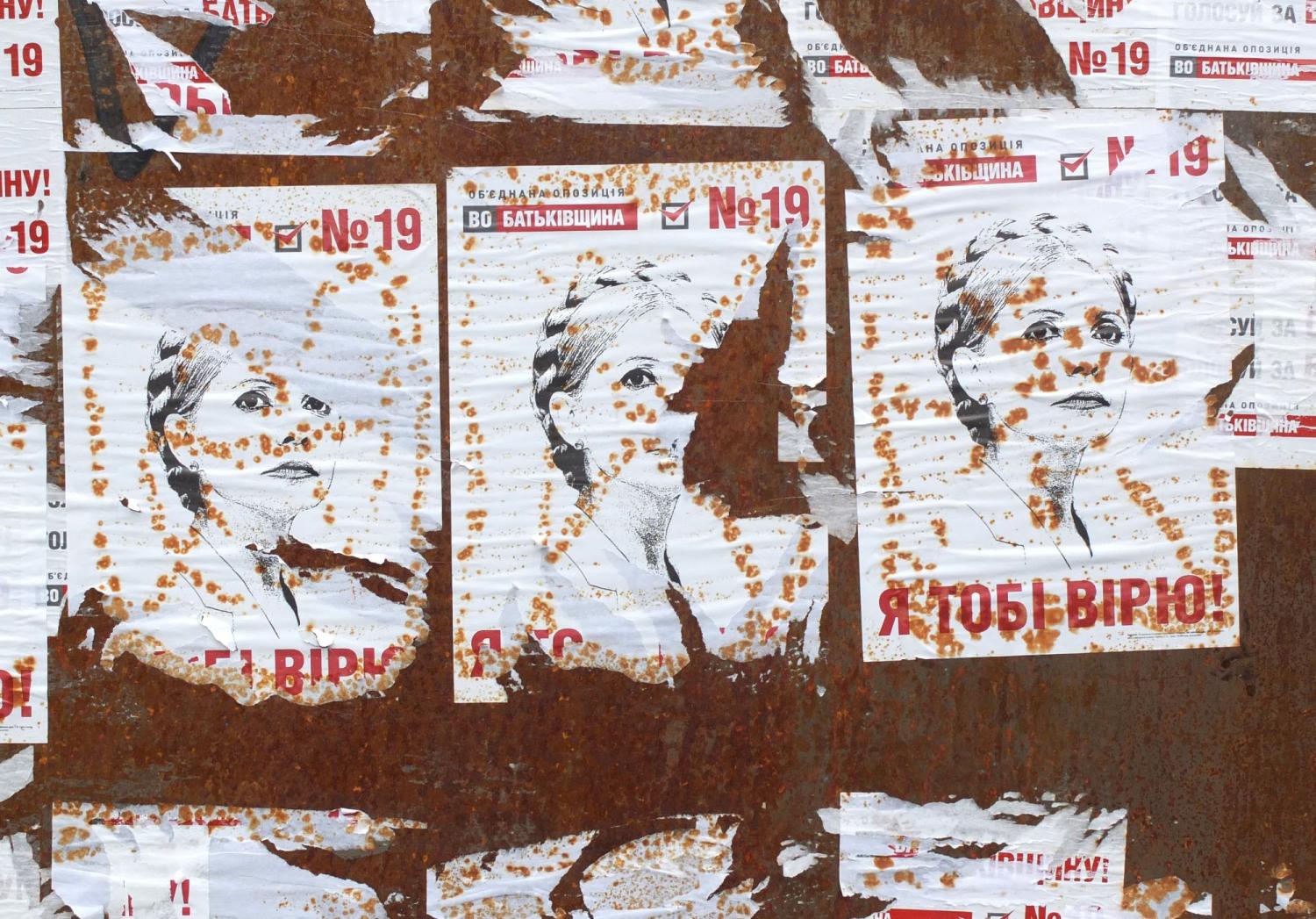

Then there was Yulia Tymoshenko, the beautiful gas princess with a braided crown, bedecked in couture outfits, who accumulated her wealth by importing Russian gas to Ukraine and whose one-time business associate, another former Kuchma-era prime minister, Pavlo Lazarenko, fled to Switzerland on a Panamanian passport after embezzling hundreds of millions of dollars from the Ukrainian budget and was ultimately detained, tried, and imprisoned for money laundering in California.

Tymoshenko backed Yushchenko in his 2004 presidential bid and rallied the crowds on the Maidan when the election was stolen. When Yushchenko became Ukraine’s third president, Tymoshenko became his prime minister, the highest post a woman has occupied in Ukraine to this day. The plot thickened and became difficult to follow: the Orange coalition soured, Yushchenko dismissed Tymoshenko after just seven months, and—plot twist—made a deal with his former arch-rival Yanukovych. Yet Tymoshenko came back as prime minister in 2007.

In 2010, Yanukovych ran against Tymoshenko, won to become Ukraine’s fourth president, and went on to shove her in prison. Together with his two sons and their business associates, Yanukovych and the Family, as they became known, proceeded to rob Ukraine’s coffers with unprecedented abandon. Ukraine slid from 134th place, out of 183, in the Transparency International corruption perception index to 152nd.

Curtain drop.

Post-Orange blues

Early in 2013, my family and I moved to Ukraine for six months so that I could complete fieldwork on my Ph.D. dissertation about Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament. This was the longest continuous time I spent in my home country in 13 years—and in my hometown of Lviv—in 20 years. Since leaving Ukraine in 2000, I had become a veritable global nomad, with stints of various lengths in London, Almaty, Prague, Baku, Maine, and finally Budapest, where I enrolled in a doctoral program at Central European University (since expelled by Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán, a Putin admirer, to Vienna). I knew nothing about nuclear weapons, but I knew for certain that whatever I was to research and write would have to be about Ukraine. Cultural competency, yes, but also that darn inculcated sense of civic duty to contribute to Ukraine somehow, even if I bailed on building it in situ.

It is no secret that living in a place is very different from watching it from a distance or visiting for holidays—or revolutions. To a visitor, Lviv transformed immensely, getting a handsome facelift of its Renaissance downtown, brimming with cafes, bookstores, and fashion boutiques. There were supermarkets, DIY stores, and IMAX cinemas. Kyiv was in a different league altogether: awash in nouveau riche money, it was alleged to have the greatest number of Bentleys per capita of any European capital. Yanukovych himself was rumored to live in an ostentatious palace outside of Kyiv, featuring a private zoo, a floating galleon of a reception hall, and golden toilets.

Meanwhile, anything that relied on state funding such as education, medical services, and public agencies and works remained in an embarrassingly pitiful state. I now had three kids in the care of the Ukrainian educational system: two in elementary school and the youngest in kindergarten. I was astonished by how little had changed since I was a schoolgirl back in the Soviet days. Portraits of Lenin and red flags were gone, of course, and brown woolen uniforms were replaced with navy blue. There was, happily, a choice of much more attractive stationery, notebooks, and pens. But otherwise—the same dilapidated hallways, antiquated analog classrooms, dreadfully boring textbooks, and underpaid teachers, while simple supplies like blackboard chalk and toilet paper relied on parents’ contributions. A state whose president defecated in a golden toilet could not provide toilet paper for its schoolchildren.

Life plodded along and Ukrainians made do. Economically, Ukraine had seen worse. GDP grew 4.1 percent in 2010 and 5.4 percent in 2011, before stagnating at zero or close to it in 2012-2013. But the political malaise was palpable, and the popular mood, as much as one could gauge it, was that of apathy and resignation. That the Orange Revolution, such a monumental and inspired collective effort to rescue the country from the clutches of oligarchic dysfunction, could in the end fail so spectacularly to prevent this very dysfunction was as poignant as it was disheartening. There will never be another Maidan, I kept hearing.

The future is now

On November 21, 2013, Mustafa Nayyem, a Ukrainian journalist of Afghan descent, posted on his Facebook page: “Come on, let’s get serious. Who is ready to go out to the Maidan by midnight tonight? ‘Likes’ don’t count.”

This was a call for action in response to President Yanukovych’s sudden refusal, under Russian pressure, to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union, scheduled for November 29 in Vilnius, Lithuania. The Association Agreement would have forged closer political and economic ties with the EU, but at a price: the Ukrainian government had to implement a program of reforms, economic, judicial, and regulatory, as well as release political prisoners such as Tymoshenko. For many in Ukraine, it was this outside leverage on Ukraine’s extractive political and economic elites that provided a faint ray of hope for curing their country, the 21st century’s sick man of Europe.

The students were the first to answer Nayyem’s call and show up in numbers to the Maidan. This was a new generation of Ukrainians, kids born after independence, entirely untouched by the Soviet experiment, only handicapped by its aftermath. During the Orange Revolution, they would have been in elementary school, some of them might have made trips to the Maidan with their parents, others would have stayed with their grandparents while their parents protested.

But in November 2013, it was this generation’s future that was on the line with the EU association decision. For them, Ukraine’s place in Europe was not so much a matter of common historical and cultural heritage. They cared little that the medieval Prince Yaroslav the Wise of Kyiv married off his daughters to the royal houses of Hungary, France, England, and Norway, becoming the “father-in-law of Europe”; even less that the Ukrainian lands were part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—once the largest and mightiest kingdom in Europe—for far longer than they were under Russian rule; and not at all that Europe’s geographical center allegedly lay somewhere near the town of Rakhiv in western Ukraine.

For the Ukrainian students on the Maidan, “Europe” was about the future, from which their corrupt leaders had barred them.

For the Ukrainian students on the Maidan, “Europe” was about the future, from which their corrupt leaders had barred them. “Europe” was about not having to pay bribes to petty bureaucrats. It was about going on an Erasmus exchange to another European university. It was about crossing Schengen borders without visas. It was about not being run over by a Bentley, whose driver would go unpunished. It was about living with clean air and drinkable water, about recycling and picking up dog poop. It was about public funds channeled toward public goods, not into private pockets. In short, Europe was about the freedom of choice and living in dignity.

Over the next few days, the students continued to gather on the Maidan under a sprouting of the EU’s blue star-studded flags and slogans like “Ukraine is Europe!” The Maidan became Euromaidan. The students sang and listened to speeches by activists and artists, but it looked as if the protests might fizzle out before too long.

At 4 a.m. on November 30, with only a few hundred still encamped on the Maidan, the Berkut riot police, armed with tear gas and truncheons, moved in and began dispersing the protesters by force. Dozens of students were cruelly beaten, some ended up in hospitals; others took refuge a short distance from the Maidan in St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery, rebuilt by Yanukovych’s former patron Kuchma, in place of the original that had been demolished by Stalin in 1937.

As the morning of November 30 dawned, the fog of events was still thick. One thing, however, was clear: that night, something critically important shifted in Ukraine. As Marci Shore, a Yale historian, wrote in her book The Ukrainian Night: “Yanukovych had broken an unspoken social contract: in the two decades since independence, the government had never used this kind of violence against its own citizens.” The Berkut pogrom marked a point from which the student-driven Euromaidan began its transformation into the nationwide Revolution of Dignity, setting in motion events that would change the course of history.

Learning civics

Max Weber, a German sociologist and political thinker, famously defined the state as possessing a monopoly on the use of legitimate force. The events in Ukraine in the winter of 2013-2014 turned Weber’s definition on its head. The use of violence on the Maidan authorized by Yanukovych as the head of state turned a huge portion of the Ukrainian society against him and ultimately cost him his legitimacy as president.

After the assault on the Maidan, the number of protesters swelled to the hundreds of thousands: the parents of the beaten students came out, the generation of the Orange Revolution, as well as those who never protested before. For all, the brutality police inflicted on defenseless students, who exercised their right to peaceful protest, touched a nerve already rubbed raw by a government that absolved itself of any accountability to the people who elected it. The protesters’ demand was no longer just the association with Europe; it was the resignation of the Yanukovych government and the return of the 2004 constitution that curbed the power of the president.

In the coming weeks, the numbers on the Maidan only increased, reaching nearly 1 million on December 8. That day, the statue of Lenin in central Kyiv was toppled. The coming months saw what Ukrainians came to call Leninopad, Lenin-o-fall, with more than 500 Soviet-era monuments demolished. Ukrainians were cleansing their country of the Soviet debris.

Not only did the Maidan grow bigger, but it dug in deeper. Miraculously swift and effective feats of self-organization produced food, shelter, and medical care for the population of the Maidan, as well as a library and a university, offering free lectures, a press center, and a security force. There was, of course, the stage and performances, but this new Maidan was markedly different from the Maidan of 2004. It was a city within a city, a polis. The protesters were no longer protesters, they were citizens of the Maidan, sustained by common purpose and gift economy, as noted by another Yale historian, Timothy Snyder. The Maidan welcomed an eclectic procession of foreign dignitaries, from the French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévi to U.S. Senator John McCain and Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland, who famously partook in the gift economy by handing out chocolate chip cookies.

Most important, perhaps, was that in this polis Ukraine’s civic nation was born. Russian propaganda attempts, grasping at the presence of right-wing groups on the Maidan, to portray the protest as an ultranationalist revolt were laughable to anyone who set foot at the Maidan in Kyiv and other cities across the country. The Maidan’s citizens were Ukrainian and Russian speakers from all walks of life and every ethnic background. They were united not by language, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, but by a commitment to shared civic values.

There would be no more eloquent vignette for this remarkable development than the flash mob at the Privoz fish market in Odesa, a Russian-speaking Ukrainian port city with prominent Jewish heritage, where musicians of its famous Philharmonic Orchestra, led by a Venezuelan conductor, sprung up, among the portly ladies presiding over heaps of fish carcasses, with violins, cellos, flutes, and trombones to triumphantly join in Beethoven’s 9th symphony, Ode to Joy, the EU anthem.

The truth of power

Yanukovych’s attempt to disperse the protests by force backfired spectacularly, as did his attempt to outlaw protests and other civil freedoms by draconian laws, modeled on Russia’s and promptly passed by the parliament he controlled on January 16, 2014. The Maidan stood firm, exposing Yanukovych’s powerlessness.

The concept of power is central to politics, yet it remains surprisingly muddled and overstretched. Power tends to be treated as synonymous with authority, force, violence, and coercion, all of which denote ways in which one man (and it’s usually a man) can bend others to his will and make them do something they wouldn’t otherwise. This, no doubt, is how the Yanukovychs—and Putins—of the world see it, too.

Hannah Arendt, a refugee from Nazi Germany and one of the most original minds of the 20th century, was among the few political thinkers who attempted to draw meaningful distinctions between the various terms we conflate with power. In her essay On Violence, Arendt recognized that while power and violence often come in tandem, they are actually complete opposites.

Power, she argued, is not the ability to impose the will of one man over another, but the ability to act in concert. Power is the property of the collective, and a single actor can be powerful only in as much as he has the following of many. Power is generated through persuasion and demonstration. Because the support for power is granted through free choice and can just as freely be withdrawn, power comes with accountability.

Violence, on the other hand, is the property of a single actor, individual, or institution. While power is the end in itself, violence is always instrumental and requires implements: physical strength, soldiers, and guns. Violence distorts equality between actors and obliterates the freedom to choose, which is so essential to power and the responsibility it entails. Power relies on support, violence commands obedience. Power needs no justification but does need legitimacy; violence can be justifiable but never legitimate.

Arendt acknowledged that, in practice, all forms of government, including democracies, rely on a combination of power and violence. All forms of government, including tyrannies, rely on the general support of society, too. To forge this support, a tyranny sooner or later turns to coercion, which necessarily diminishes its power and makes it, in the words of Montesquieu, the most violent and the least powerful form of government. Thus, the resort to violence is nothing else but a symptom of eroding power, an Arendtian lesson Yanukovych—and Putin—would have done well to learn.

Pride and premonition

By the time the Revolution of Dignity started in November 2013, I had moved back to the same small town in Maine where I met the Orange Revolution. I was a Ph.D. student with three kids in elementary school, one chapter of my dissertation half-written, a horde of archival document scans and interview transcripts in my computer, and not a single contact in U.S. academia. No work on the dissertation would be accomplished through the winter of 2014.

I spent all available time glued to the computer, following daily developments on the Maidan and pouring over countless articles, many of them written by pundits who suddenly woke up from Ukraine fatigue to opine on developments in a country they knew little about and understood even less. I pitched op-ed after op-ed but got rejection after rejection. I contemplated going to Ukraine, but I did not want to be a revolution tourist and felt that if I were to go, I’d have to stay and see it through—an option I could not square with responsibilities to my family. The Ukrainian diaspora the world over mobilized and raised money and supplies for the Maidan, and I took part. I also volunteered for an online news portal, Euromaidan Press, one of those miraculous products of self-organization, that promptly translated real-time news from the Maidan into English.

I watched the events unfold with a mixture of pride and premonition. There was the resolve: ordinary people’s commitment to defend civil rights and freedoms against arbitrary brute force. There was the resourcefulness: millions of Ukrainians managed to create something great out of limited resources. There was the creativity and humor: the merciless taunting of Yanukovych and the oligarchs. There was also the benign irreverence toward all politicians, including opposition figures like the heavyweight boxing champion Vitali Klitschko, the liberal technocrat Arseniy Yatsenyuk, and the dour nationalist Oleh Tyahnybok. This also extended to the EU delegations that shuttled between Brussels and Kyiv to try and mediate the crisis but were said to have brought a baguette to a gun fight (a sentiment less delicately echoed by Nuland—“F-ck the EU!”—in a conversation with U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt, clandestinely intercepted and generously leaked to the public by Russian intelligence).

This was no Woodstock.

But something more ominous was in the air. Reports emerged of disappearances and the torture of Maidan activists, some of them snatched from hospital beds where they were recovering from police beatings. In freezing temperatures, the Berkut surrounded the Maidan and began subjecting the protesters to water cannons, tear gas, and stun grenades. The Maidaners donned balaclavas, ski goggles, and construction helmets; armed themselves with baseball bats and ply-wood shields; dug up paving stones; mixed Molotov cocktails; and erected barricades of sandbags, ice, and tires which were burned to create smoke screens. This was no Woodstock.

On February 18, 2014, the Berkut riot police received orders to “clean up” the Maidan and moved in en force. Images of a wall of shields and police helmets, water cannons, black smoke, men in orange hardhats with Molotov cocktails, sullen volunteers in a make-shift hospital treating gory wounds from live bullets and stun grenades were transmitted around the world. By February 20, some protesters were being picked off by snipers installed on nearby rooftops. When the smoke of the Battle for the Maidan cleared, over 1,000 were injured and 108 protesters and 13 police were dead. From then on, the fallen protesters would be honored as the Nebesna Sotnya, the Heavenly Hundred, the first casualties in the struggle for Ukraine’s European future.

It was an unthinkable toll for a society that treated the beating of the students as an unacceptable red line. The slaughter on the Maidan was a step too far even for Yanukovych’s own political party, which moved to distance itself from the man who now had blood on his hands. Yanukovych first lost legitimacy, then power, and now authority. Hastily packing some papers and belongings, Yanukovych fled to Russia, leaving behind his gaudy mansion, golden toilets and all.

Rejected, Russia strikes

While the standoff on the Maidan was nominally between the Ukrainian protesters and the Ukrainian government, Russia’s heavy, dark shadow hung over the ordeal. It was not only that Yanukovych was swayed by Putin’s promise of a $15 billion bribe not to sign the EU Association Agreement; not even that many in Yanukovych’s cabinet, especially in the defense and security apparatus, had Russian passports, allegiances, and business ties. Rather, it was that Yanukovych tried to institute in Ukraine what Putin had managed in Russia.

But the Maidan revealed just how different Ukrainians were from Russians. The Ukrainian society rejected the kind of social contract with its rulers that the Russian society accepted—whether gladly, begrudgingly, or defeatedly—with theirs. Neither the relative prosperity nor pockets of personal freedom that seemed sufficient to lull the Russian society into submission and to surrender its political agency entirely to the Putin-managed vertical of power would suffice for Ukrainians. They were willing to fight and die for the rule of law, for their political rights and liberties, and for their collective agency to shape their future. The Russian post-Soviet model of governance failed to generate a following in Ukraine, and Yanukovych failed to impose it by force. Russia proved powerless in Ukraine.

Putin, loath to accept his impotence in Ukraine, would go on to violate her.

Where power is in jeopardy, Arendt observed, violence appears and, if unchecked, takes over. As Ukraine mourned its fallen and reconstituted its government, Russia, portraying the events in Ukraine as an “illegitimate fascist coup,” pounced. At first, the Kremlin did so stealthily, sending “little green men” to take over Crimea, which it would promptly and illegally annex; then more brazenly, mobilizing and arming proxies to instigate a war in the Donbas that would claim over 10,000 lives; and finally, dropping all pretense, with an overt large-scale invasion.

Putin, loath to accept his impotence in Ukraine, would go on to violate her. “Nravitsia, ne nravitsia, terpi, moya krasavitsa/Like it or not, put up with it, my gorgeous,” Putin quoted with a smirk from a lewd Russian folk song on February 8, 2022, in a conversation with French President Emmanuel Macron, who was in Moscow trying to ascertain that the 190,000 Russian troops amassed at Ukraine’s borders would not really invade. In just over a fortnight, Ukrainians woke up to Russian tanks and missiles. Four days into the full-scale Russian invasion, Ukraine applied for EU membership.

To live free or die

With their resolve, resourcefulness, self-organization, and the gift economy, first honed during the Revolution of Dignity, Ukrainians would go on to mount a valiant resistance to the Russian onslaught, once again surprising themselves and the world. While repelling a larger, richer, better-armed adversary, Ukraine, prodded by its civil society, would continue to ferret out corrupt operators, steadily improving its Transparency International corruption perception index ranking from 152nd place in Yanukovych’s days to 104th in 2023 (while Russia slid down to 141st). On December 14, 2023, the European Council would vote to open membership negotiations with Ukraine.

Ukrainian politics would also not lose its theatrical flair: in a life-imitating-art twist, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a comedian who played a Ukrainian president bent on fighting corruption in a satirical TV show, would be elected in 2019 as Ukraine’s sixth president, defeating the incumbent, Ukraine’s fifth president, Petro Poroshenko, a diabetic chocolate magnate. When Russia invaded, Zelenskyy the comedian would turn into a steadfast wartime leader, using his communication skills to keep up morale and rally international support for Ukraine’s defense effort.

By that time, I had defended my dissertation and published a book about Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament, a topic made suddenly relevant by Russia’s aggression and its attending nuclear threats. Although I am no longer a voiceless Ukrainian Ph.D. student from an obscure European university struggling to find a publisher, I now struggle to find the words to convey the unfairness and horror of the war Russia unleashed in Ukraine. If tear gas and truncheons were unacceptable in 2013 and the death of a hundred was unthinkable in 2014, the slaughter of many thousands, the displacement of millions, the mass graves, gang rapes, child abductions, and torture chambers that followed in the wake of the Russian troops since February 2022 are unspeakable.

Meanwhile, amid air raid sirens, Russian missiles, and unending fresh graves, a new generation of Ukrainians is coming of age. These young people no longer hail from a country known only for its corruption, they hail from a country known for its valor, from a country where ordinary people are wresting, in an unequal battle, their freedom from a vicious foreign tyrant, while continuing to put their own messy house in order. These young Ukrainians will no longer awkwardly linger on the threshold of “Europe,” waiting to be admitted: they are part of the polity that pays the highest price to defend everything Europe stands for. And like me, when I see a New Hampshire license plate, they now know what “Live free or die” truly means.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The author would like to thank Adam Lammon for editing and Rachel Slattery for layout.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

When Ukraine set course for Europe

The Revolution of Dignity, a decade later

February 20, 2024