Nearly two decades ago, the United Nations passed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This treaty, ratified by 191 of 193 member states, includes a commitment to ensuring people with disabilities have access to inclusive education. Despite the best intentions, however, children with disabilities and their families continue to face substantial barriers to accessing quality and inclusive education within their communities as their rights vary greatly across countries. Significant work remains to ensure that inclusive education serves the needs of the estimated 10 percent of children with a disability around the world.

In the field of family, school, and community engagement, the level to which a parent or caregiver gets involved in schools is often treated as a choice. They can decide to get involved in a committee or attend a back-to-school night. For many families of children with disabilities, being involved in their child’s learning and school is a must. Across social, economic, and political divides, families are the frontline champions for their children with disabilities and are fierce advocates holding education systems accountable for meeting their children’s rights. Families around the world spend countless hours navigating complex education and healthcare systems and advocating for their children’s rights and needs to make sure they can attend school and learn. According to Christina Cipriano, an educational researcher and parent of children with disabilities, “The barriers that families of children with disabilities face are a constant reminder that the systems they operate in were not designed to include their children. Positioning families as partners in their child’s education is essential to ensuring their needs and rights are upheld.”

Education leaders, scholars, and practitioners working to support family, school, and community engagement have much to learn about building stronger partnerships and relational trust from families of children with disabilities. As a team of education experts from the Center for Universal Education (CUE), Special Olympics International, Inclusive Development Partners (IDP), and the Education Collaboratory at Yale we came together to identify the ways that families of children with disabilities are engaged in their children and to address barriers to deepen partnerships between homes and schools. In April 2024, we facilitated a workshop to share global research and strategies on inclusive family, school, and community engagement practices at the Symposium on Education Systems Transformation for and through Inclusive Education. We convened key policy and decision makers, researchers, practitioners, and learners with intellectual disabilities to discuss strategies on how to transform education systems to be truly inclusive for learners with disabilities. Below we share some of the lessons on family, school, and community engagement from our collective work, and a workshop plan for school educators, education leaders, and organizations striving to identify barriers to and opportunities for stronger family, school, and community partnerships.

Position families as allies to foster proactive collaboration

Families are engaged in their children’ education in a multitude of ways. In the field of family, school, and community engagement, there are six major types of family engagement as developed by Joyce Epstein and colleagues.

Figure 1. Types of family involvement and engagement with schools

Families of children with disabilities are involved in all these areas, but the time and energy they spend in areas like caregiving and supporting learning at home is often far greater than other families. Families of children with disabilities also have to frequently communicate with schools in order to ensure that their children have their basic needs. According to Anne Hayes, co-founder and executive director of IDP, “Constant and frequent communication is key to ensuring a team approach to inclusion and being sure that the school presumes competence and promotes academic and social inclusion.”

The ways that families of children with disabilities communicate with schools varies across context. For example, in the United States, families and educators meet at regular intervals about student progress using Individualized Education Plan meetings. In many parts of the world, however, there are few formal processes or interfaces with schools and most communication is informal. In Nepal, IDP found that learning institutions are often segregated based on ability. Parents may have to send their child to another part of the country to attend school and go months without seeing their child or communicating with the school because of financial constraints.

Families of children with disabilities often have more demanding caregiving responsibilities, which are disproportionately shouldered by mothers around the world. Families of children with disabilities also spend more time and resources adapting materials, obtaining accessible devices, and have to seek outside tutoring, physical and cognitive therapies, and other critical services to support the health and learning of their children.

Ideally family engagement is proactive, meaning parents/caregivers collaborate with schools to ensure children have support and accommodations they need to succeed, More frequently, however, engagement with schools is reactive and families must regularly advocate for their children’s basic rights and needs. A parent in Zanzibar, Tanzania whose child has both intellectual and physical disabilities described in an interview with IDP that they had to go to school during meals to ensure her child was fed because the teachers did not have the time and resources with a crowded classroom according.

Advocacy and building community form a significant part of family engagement, as families work together with schools, community organizers and healthcare professionals to advocate for their children’s rights and needs. In this 2023 Special Olympics International report, families and young people with disabilities lay out some of the key recommendations including supporting families’ and schools’ capabilities to effectively advocate for and support the needs of children with disabilities.

Collectively break barriers to strengthen partnerships

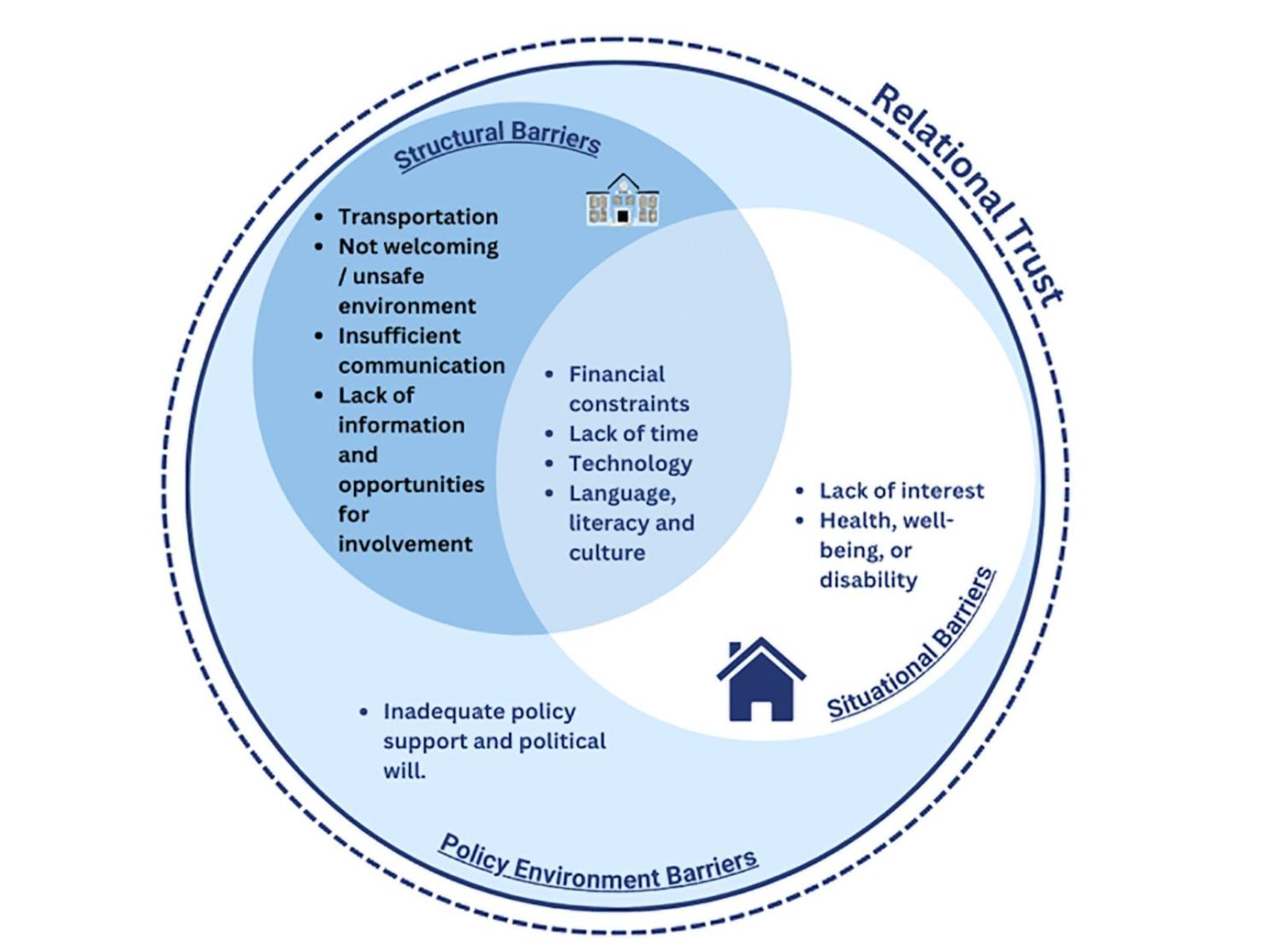

Families of children with disabilities face multiple and intersecting barriers to building strong partnerships. Some of these are structural in nature, such as lack of adaptive equipment and sufficient services available in schools and clear and open two-way communication with schools. Other barriers are situational, such as the health and wellbeing of caregivers and family circumstances. The Family, School, and Community Engagement initiative at CUE has been mapping barriers to building strong family engagement across continents.

Figure 2. Barriers to family involvement and engagement with schools

Structural barriers create stress for families as they seek to advocate for their children, prevent strong partnerships, and often overlap with situational barriers. Schools often lack infrastructure and personnel, so families must devote more time and financial resources to engaging with schools in order to ensure that their students are adequately served. For example, some parents in Malawi had to serve as teacher assistants or paraprofessionals to ensure that their child with an intellectual or developmental disability is enrolled into school. This puts extra strain on families living in poverty and without flexible and stable work. Mothers experience limited earning potential as they often take on caregiving responsibilities. The double burden of poverty and inequitable access to resources and services further exacerbates a families’ ability to support their child’s learning.

Another major structural barrier to strong family, school, and community partnerships is bias, stigma, and deficit-thinking among staff, educators, and other families and students in schools, which contribute to exclusionary school environments. Children with disabilities are often labelled and sorted based on disabilities and perceived levels of support needs, and experience bullying and lowered educational expectations from educators, impacting their learning and well-being. As Anne Hayes noted, learners with mild and moderate disabilities often are allowed to attend schools, but children who have more complex disabilities might be placed in segregated institutions. Families of children with disabilities commonly report fewer opportunities to be involved in their children’s learning and school as they are less likely to receive report cards and may be excluded from family days and other family engagement events at schools. Families, especially mothers, around the world reported experiencing blame and shame, as children’s behavior and school performance are often attributed to poor parenting. Discrimination based on race and ethnicity also limits access to vital information and further marginalizes families of children with disabilities. An important role of family, school, and community partnerships is to mitigate some of the stress that families of children with disabilities face when engaging with schools, particularly those experiencing multiple levels of marginalization.

Dedicate time and effort to building relational trust

Trust is not built through one parent-teacher conference or school event.

In recent research conducted by CUE in collaboration with schools and community organizations on six contents, participants across countries and demographics noted a blame game between families and educators. Educators often felt that families were not sufficiently motivated and interested in their child’s education, while families felt that educators often blamed them for challenges to their children’s learning and development.

Naming and breaking the blame game, and using approaches to build relational trust between families and educators, is critical to supporting all children, especially children with disabilities. Relational trust is both the foundation for and the outcome of effective family, school, and community partnerships and leads to better schools and school outcomes. Tools like CUE’s Global Family, School, and Community Engagement Rubrics and Conversation Starter Tools can help schools reflect on and assess how they are engaging with families and promoting welcoming and inclusive environments.

Trust is not built through one parent-teacher conference or school event. It begins with seeing children with disabilities and their families as assets and experts on their children. When schools listen and seek to understand families’ beliefs and experiences, and embrace our differences, it builds authentic relationships. As adults, parents, caregivers, and educators can model healthy curiosity and engage with children with disabilities, rather than look away. As Dr. Christina Cipriano shared in the Washington Post, “Parents can model humanity and, with their children, develop scripts of what to say in the name of healthy inquiry.”

In her new book, Be Unapologetically Impatient, Cipriano draws on her own experiences as a parent of children with disabilities and shares evidence-based strategies for how families can harness the power of their positionality as unique and powerful vantage points from which to effect change in their children’s schools and community. She invites and encourages all adults who are invested in supporting children with disabilities to recognize their role in being change agents and instructs them how to work together to advance the opportunities, livelihoods, and joy for all children and families.

Facilitate intentional conversations on how to build strong family, school, and community partnerships

As family members, educators, school leaders, and community organizations, it is important to have dialogues in our communities and schools on how to build stronger partnerships between schools and families of children with disabilities. To support your efforts, we are sharing a facilitation guide we developed based on research and our experiences as educators and families of children with disabilities. It is through intentional and continuous partnerships with schools that we can ensure that children with disabilities not only have their needs met but can flourish. Our own families teach us so much; let’s invite families of others to teach us, too.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What we can learn from families of children with disabilities about inclusive family, school, and community engagement

January 16, 2025