The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. government or the Department of Defense.

When Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, predicted in January that it will take at least 15 to 20 years before we have a “useful” quantum computer, his comments caused a stir. The value of quantum computing stocks sharply fell, and quantum computing companies were quick to rebut his remarks, pointing to a small commercial base that is paying to solve some optimization problems now. However, many hold Huang’s belief that current quantum computers are a long way from surpassing current computers in applications like simulating complex chemical reactions, cracking encryption, or enhancing machine learning. Further, Huang’s assessment conflicts with assertions that quantum computing is on the verge of a “moonshot” moment. Is a giant leap forward in quantum computing ahead of us?

There are many efforts underway that channel this enthusiasm about a quantum moonshot. The National Quantum Initiative Act (NQI Act) was passed in 2018. Since then, the U.S. government has been monitoring progress in quantum science closely while developing policies to accelerate development in key areas like computing; however, not only is it premature to launch a national quantum computing push on par with the Apollo program, but the United States must balance investments in quantum computing hardware development with other areas of quantum science. The computers that we are most familiar with, classical computers, underwent decades of development to become reliable, fast, and small. Quantum computers face even tougher engineering hurdles to do the same. Additionally, there are currently many competing approaches to building a quantum computer, but none of them have a clear path to becoming reliable, fast, and small enough to tackle the tough problems that classical computers truly cannot touch. While progress is being made on reliability and speed, to launch a moonshot effort, at least one approach, preferably two or three, must have a viable path to overcome the engineering challenges required to scale up to the level required to tackle the much-hyped applications.

As this is sorted out, the U.S. government should boost efforts in academia and industry to expand the quantum workforce. The U.S. Congress recently proposed a bill to amend the NQI Act to strengthen public-private cooperation in quantum science. This is welcome for those already in the field, but traditional educational paths are not currently meeting the demand for quantum experts or quantum-informed managers and policymakers, which hinders long-term progress. Quantum science programs must evolve to be cross-disciplinary, and new pathways must be established to cross-train mid-career scientists, engineers, and computer scientists.

Overprioritizing quantum computing efforts also threatens to draw resources away from three areas poised for progress now: overcoming the engineering hurdles preventing wider fielding of quantum sensors; implementing quantum-resistant encryption algorithms for data that will remain sensitive for longer than 15 years; and expanding the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to solve tough problems in quantum science—the kind many thought a quantum computer was required to solve.

The primer that follows is designed to help those with no background in quantum computing understand the commentary and recommendations that begin with the section “Why Jensen Huang is right.”

What is a quantum computer?

Huang recently noted that the term “quantum computing” conjures unhelpful comparisons with the desktop computers or handheld devices that we interact with every day. They execute programs or applications at the click of a mouse or touch of a finger. When we describe the innards of these computers, we talk about circuit boards and electrons flowing through transistors. These computers’ behavior can be described by the classical (i.e., pre-quantum physics) understanding of electricity and magnetism; hence the moniker “classical computer.”

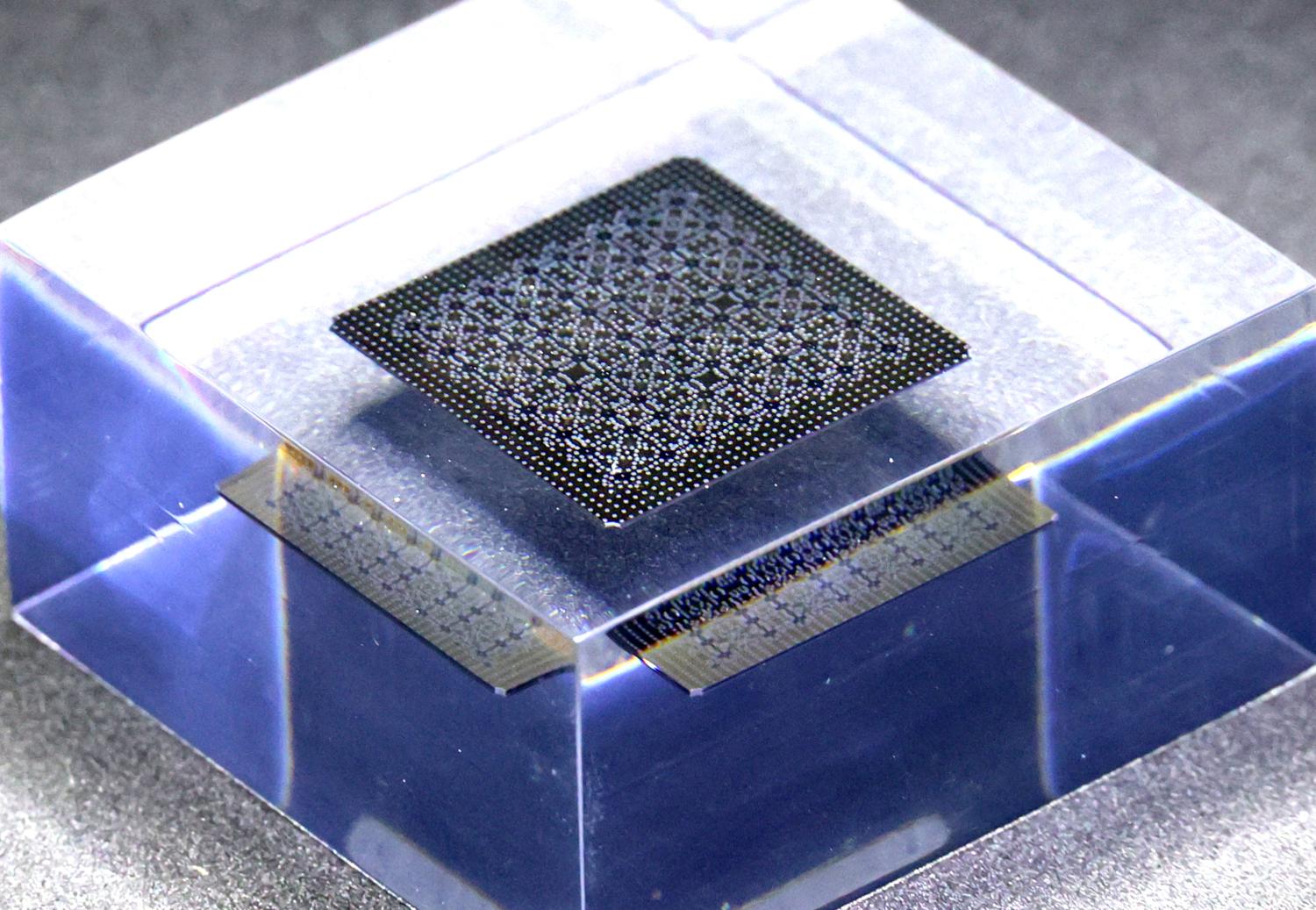

A quantum computer is different: it is more accurately described as a physics experiment that can solve a problem. The images that come to mind from the term “physics experiment” better resemble the quantum computers of today, like the image below of Google’s quantum computer. This computer does not play games, do word processing, surf the web, or display images on a screen. While surrounded by classical electronics and machinery, the true computing innards of a quantum computer are the internal states of an atom, which can only be described by quantum physics, hence the term “quantum computer.”

All the equipment in the image above is used to house and manipulate qubits—the unit of quantum information. A classical computer uses bits that can take the value of either zero or one by changing the electrical charge of the bit. A qubit uses two internal states of an atom, for example, to be the zero and one values, but a qubit also takes advantage of the wave-like properties of matter described by quantum physics to be in a combination of the zero and one states (called a superposition) during the computation process. This creates some very important differences between how a classical and a quantum computer function.

At every stage of a classical computation, the value of the bits can be read out of memory, and for many types of problems, at the end of the computation, there will be a single, repeatable result. This is not the case with a quantum computer. When the qubits are measured at the end of a calculation (the quantum version of “reading out”), the qubits will take on the values of either zero or one, like bits; however, the values measured are based on the probabilities of quantum physics. Running the same quantum calculation many times can produce a range of results, with some results occurring more frequently than others, which means the result you measure may not be the answer you seek.

Quantum computing: powerful but delicate

The power of quantum computing lies in the effectiveness of a quantum algorithm’s (i.e., a “program”) ability to either make the solution you seek the most probable possibility you measure or to ensure that any possibility you measure contains some information about the solution you seek—and a quantum computer can do this over an unimaginable number of possibilities. As the number of qubits in the calculation rises, the potential solution space grows exponentially. A single qubit accounts for two possibilities; two qubits, four possibilities, and so forth. A 2048-qubit sequence encodes 2^2048 possible combinations, which is a number 617 digits long. Numbers we are more familiar with, like a billion or a trillion, are 10 and 13 digits long, respectively.

A common misunderstanding that has persisted for decades is the idea that a quantum computer simultaneously computes all these possibilities and spits out the correct result. This isn’t the case. A quantum computer must iterate many times until it is highly unlikely to measure anything but the correct solution.

In two highly recommended videos, Grant Sanderson illustrates how this works for a quantum computer running Grover’s algorithm. The goal of Grover’s algorithm is to search a collection of potential solutions to a problem for a correct solution—a useful tool for a problem where solutions are easy to recognize but hard to calculate. Some classes of optimization problems, like the traveling salesman problem, fall into this category. In this problem, a traveling salesman needs to visit a selection of cities once using the shortest possible path while returning to the starting city. It is hard to find the solution for a large number of cities by brute force, but it is easy to generate proposed routes and verify if they are shorter than a desired value. A classical computer would check each possible solution in the set one by one until it found the correct one. As the set of possibilities grows, the time it takes to find the solution also grows. If the set doubles in number, the average time to find a solution also doubles for a classical computer for this type of problem.

A quantum computer will not likely identify the correct solution after one iteration (even if it did, you wouldn’t have any confidence it is correct), but what it can do still feels magical. As the set of possible solutions grows, the quantum computer will only require the square root of this number in iterations. If the set size grew a million times larger, the compute time for a classical computer would grow a million times longer; for a quantum computer, it would only grow by a thousand times. By the end of these iterations, the result delivered by the quantum computer is, to a high degree of statistical confidence, the correct answer. The iterations of a quantum algorithm are more effective than the blind searching of a classical computer.

Qubits are a powerful computing tool, but they are also very delicate. Imagine a house of cards. It is very touchy to build and, once built, it is only a matter of time before it falls. The slightest bump or puff of air will cause a collapse. Now imagine a house of cards so delicate that a stray beam of light knocks it over. Now you are beginning to understand how fragile a quantum computer is. A quantum chip like the one below has 64 qubits and resides in the bottom layer of a cryocooler such as the one in the image above. When in operation, the cryocooler is surrounded by a metal shroud that further shields the qubits from interference.

There are many ways to form a qubit (e.g., atoms, ions, electrons, photons); many, like Google’s 105-qubit Willow chip, are only stable if cooled to within a fraction of a degree from absolute zero (zero degrees Kelvin), which is why the engineering complexity of a cryocooler is required. Interference from the environment (collectively termed “noise”) comes in many forms: vibrations, electrical fluctuations, heat, light, and the natural random fluctuations within the atom itself. The time an individual qubit remains stable is called the “coherence time,” which can range from microseconds to minutes depending on the type of qubit used. The rules of quantum physics also prevent us from making copies of a qubit in an unknown state (i.e., cloning) in an attempt to extend the computation time with a “fresh” qubit. Consequently, processing exabytes (1 billion gigabytes) worth of data simply will not be a quantum computer’s forte.

Noise crashes a quantum computer. Returning to the house of cards analogy, it is possible to build a quantum computer with redundancy so that if one or more cubits succumb to noise, it will not crash the computation. This is enabled by another delicate phenomenon from the quantum world: entanglement. This allows two qubits to be linked, meaning that operations performed on one qubit influence its linked partner. The grouping of qubits to increase the chances that they function as a single error-free qubit for a longer time is called error correction.

Depending on the type of qubit used, the total number of qubits (physical qubits) required to produce the equivalent of a single error-corrected qubit (logical qubit) ranges from as few as 10 to more than a thousand. For reference, the total number of qubits achieved to date (publicly announced) is just under 1,200 qubits. In October 2023, Atom Computing announced that it achieved 1,180 qubits using atoms as qubits, slightly edging out the 1,121-qubit IBM Condor processor, which uses superconducting circuits. Hence, the total number of physical qubits achieved today may only represent one to 100 logical qubits. Google, IBM, Microsoft, and others are now incorporating error correction into their chip designs. While the highest cubit count achieved is an interesting metric for charting progress in quantum computing, the number of logical qubits is a better metric for comparing different quantum computers, but there is one more thing to consider.

Even with error correction, noise will eventually overcome the calculation—Mother Nature will knock down the house of cards. Executing a quantum algorithm is a race against time. All the algorithm’s operations must be performed and measured before the house of cards falls. Thankfully, some quantum algorithms, like Shor’s algorithm for factoring prime numbers, are iterative, using both classical and quantum computing steps. The step that requires a quantum computer in Shor’s algorithm can be done within the coherence time of the qubits, provided the operations can be performed fast enough. While you can find published coherence time data for qubits, many quantum computing roadmaps now list the total number of operations that can be performed as the key metric, which better captures how the qubit coherence time, speed of operations, and error rates affect performance. The bottom line, however, is that the qubit’s fragility makes achieving the power of quantum computing very difficult.

Why Jensen Huang is right

We can now put all these concepts together to see why many agree with Huang’s outlook. A quantum computer that can factor large prime numbers (i.e., execute Shor’s algorithm), with the threat it poses to cryptography, is what immediately comes to the minds of many as a “useful” quantum computer. A 1024-bit key (i.e., a single prime number represented by a series of 1,024 ones and zeros) is estimated to take 500,000 years for a single computer processor to factor, potentially crackable today using thousands of processors. Factoring a 2048-bit key would take far longer. By an often-cited estimate, it would take 20 million tolerably noisy physical qubits (roughly 14,000 logical qubits) eight hours to factor a 2048-bit key. Now, imagine scaling up Google’s Willow chip over 19,000 times. A more recent estimate places the required number of logical qubits at 1,730, which would still require scaling up by over a thousand times. Neither will be possible without dramatic miniaturization.

Many of these considerations are now reflected in the technology roadmaps for quantum computing. IBM, for example, projects that it will achieve 2,000 logical qubits from 100,000 physical qubits capable of 1 billion operations sometime beyond 2033. IBM’s roadmap shows how large this computer will be. Given the fragility of qubits and the engineering complexity of error correction, scaling up the number of logical qubits is technically challenging and will take longer than the path classical computing took with bits and transistors. More engineering challenges are sure to be encountered, creating additional roadmap delays. Thus, Huang’s estimate of 15 to 20 years for a quantum computer that can handle more difficult quantum computing problems is reasonable, especially if the more recent estimate for Shor’s algorithm proves accurate.

Do we need a quantum moonshot?

What if all the engineering challenges quantum computing faces can be overcome in less than 15 years? That is part of what the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) Quantum Benchmarking Initiative (QBI) seeks to answer. The question that Joe Altepeter, QBI program manager and a self-described quantum computing skeptic, poses to industry and academia is simple: “Are you going to build an industrially useful quantum computer by 2033?” QBI will validate the claims submitted. Building on a previous effort that is currently evaluating Microsoft’s and PsiQuantum’s quantum computing technology, QBI kicked off in July 2024 and announced the addition of 16 more companies as of April 2025.

These companies enter the first of three potential stages that progressively scrutinize their proposed pathway to an impactful quantum computer from concept to research and development strategy, and then to prototype testing in the final phase. The first two stages are allotted 18 months, while the final stage is more flexible. If the current quantum roadmaps are accurate, then within the next two to three years, we would expect to see logical qubits on the order of a hundred, making quantum computers capable of more than today but still short of the weightier computations.

The industrial utility of less-capable quantum computers is tougher to predict and highlights the precarious position of quantum computing companies today, especially publicly traded ones. If quantum computing becomes more industrially useful, then company revenues, especially from nongovernmental entities, should be significantly greater than today. Rigetti Computing, which is participating in QBI, reported $10 million in revenue for 2024, with 54.2% coming from U.S. government entities. D-Wave, which is not among the announced participants for QBI, reported a revenue of $8.8 million and acknowledged government sources but did not disclose the amount. Both companies are publicly traded and last year received warnings of potential delisting from their respective exchanges. Not surprisingly, both companies, along with 11 others, participated in “Quantum Day” at Nvidia’s March 2025 GPU Technology Conference, where Huang appeared to soften his January remarks.

While the QBI is not a competition, the companies that successfully complete the third phase of the evaluation will emerge preeminent—but this does not necessarily set the stage for a moonshot. There must be at least one viable approach to achieving a quantum computer capable of tackling the tougher problems. More would be better. The Manhattan Project pursued two approaches to achieve a nuclear detonation. Project Apollo considered three main proposals for landing a human on the moon before selecting lunar orbit rendezvous. It is premature for the United States to commit to a quantum computing moonshot, but QBI could be the prelude to one.

What can be done in the meantime?

The United Nations declared 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, “recognizing the importance of quantum science and the need for wider awareness of its past and future impact.” What began as an early 20th-century effort to understand why atoms emit light the way they do now touches nearly every aspect of our lives. The hype surrounding quantum computing, however, tends to overshadow the other areas of active research in the quantum sciences. While DARPA is taking the lead on vetting quantum computing architectures for the U.S. government, academia and industry remain essential to advancing quantum science as a whole, including the following areas poised for progress.

Expand the quantum workforce

In May, the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology introduced a bill to strengthen public-private cooperation by establishing an innovation sandbox for quantum led by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). If passed, NIST will be tasked to promote “quantum computing application development acceleration for quantum, quantum communication, quantum sensing, and quantum-hybrid computing near-term use cases.” While this is great news for those already working in quantum science, it will increase the demand for additional quantum-trained professionals.

McKinsey estimated in 2022 that there was only one qualified candidate for every three quantum jobs and that less than half of quantum jobs would be filled by 2025. At the same time, McKinsey found that funding for quantum start-up companies had doubled from 2020 to 2021 to $1.4 billion. It isn’t rocket science to state that the number of quantum-savvy professionals didn’t rise by nearly the same amount.

While developing quantum hardware has long been a multidisciplinary effort, quantum science expertise typically resides in university physics and chemistry departments. University stovepipes produce physicists who know quantum science, engineers who know hardware, and computer scientists who know classical computers, but there isn’t enough cross-pollination during these programs to sustain the quantum workforce. Among industry, Google, Microsoft, and IBM offer resources to help bring newcomers up to speed.

In 2022, the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) released a strategy to develop a quantum workforce. The NSTC found that there is a shortage of talent across the spectrum of quantum science expertise, from the experts involved directly in development to professionals who need to understand quantum science enough to make informed management decisions.

For example, there are many known quantum algorithms, like Shor’s and Grover’s, that are waiting for sufficient quantum hardware to run, but many more problems are waiting for their algorithms to be developed. If a time traveler from the future were to deliver a highly-capable quantum computer today, there would be a mad dash to train more quantum computer scientists to make full use of it. The academic pipeline would eventually produce quantum-trained programmers, but it would take time. Likewise, a trained classical computer scientist wanting to make the jump into quantum computing might start here, but it would be difficult to come up to speed on their own.

The NSTC strategy encourages academic institutions to reduce the barriers to entry, including the creation of multidisciplinary programs that partner with government agencies and industry to broaden exposure to quantum science. Not everyone working in quantum science requires an understanding of quantum science with the level of mathematical rigor of a physics Ph.D. A 2024 supplement to the NSTC strategy recognizes that the United States will be unable to source all the needs of the U.S. quantum workforce domestically. The national security barriers that hinder international cooperation with allies (e.g., export controls) and the recruitment of international talent into the quantum workforce must be managed.

It is difficult to determine what progress the United States is making in addressing quantum workforce issues. The NSTC tracks the federal government’s progress on key quantum policy areas annually as a supplement to the president’s budget. The fiscal year 2025 supplement, for example, highlights the commissioning of two studies by the National Science Foundation to formally examine the quantum workforce and educational pathways. The accomplishments reported in 2024 leverage existing programs, as the strategy directs, but the impacts are difficult to measure and some feel like business as usual. Expanding the quantum workforce will not be easy or fast. The NQI Act was authorized for 10 years. As a prelude to the reauthorization of the NQI, the NSTC should provide a review of the first 10 years of the NQI in 2027 with data on the impact on the quantum workforce.

Invest in quantum sensors

Ramping up quantum computing prior to a true moonshot opportunity risks pulling quantum talent from other quantum efforts like quantum sensing, a field that can deliver new products sooner.

A quantum sensor uses a phenomenon that can only be explained by quantum physics to make physical measurements. Magnetic resonance imaging uses the quantum properties of protons and the radio waves they emit to create an image of the soft tissues in the body. Atomic clocks, which mark time by measuring the light emitted from electrons in the cesium atom, enabled the Global Positioning System (GPS) and are increasingly used in telecommunications as the speed and volume of data transfer increase. Quantum sensors have already made a huge impact, and quantum science has more to offer.

The federal government, especially the Department of Defense (DOD), has a broad interest in new quantum sensors. In March, the Defense Innovation Unit announced the selection of 18 companies to participate in its Transition of Quantum Sensors (TQS) program, which will field test many sensors, both commercially available and new prototypes, over the next 12 months. The sensors include ultra-sensitive magnetic and gravitational field sensors and quantum inertial sensors. While there are many uses for these sensors, the benefits for navigation have wider commercial applications.

For example, when GPS is disrupted, as it is daily across the globe, aircraft rely on inertial measurement units (IMUs) to estimate their position based on the last GPS fix. IMUs can be made in many ways, but a common technology used is laser gyroscopes. Laser gyroscopes use the wave-like properties of light to detect acceleration. When a gyroscope moves, it causes the laser beams of the gyro to interfere with each other (the Sanac effect). The interference is measured to infer the motion of the gyro. Like any sensor, errors creep into the measurements. IMU errors accumulate at the rate of about one mile per hour for a high-performance aviation IMU.

A quantum inertial sensor, or atomic gyroscope, is like a laser gyroscope but uses the wave-like properties of atoms to create the interference. Quantum inertial sensors could boost IMU performance by 10-fold or more over current IMUs, essentially making an aircraft immune to short GPS outages.

There are many engineering hurdles to overcome; some require additional basic research from academia, and others are integration issues suited for industry. Quantum inertial sensors are very sensitive to environmental disturbances like vibration and temperature change, but they are nowhere near as temperamental as a qubit. In February, DARPA launched the Robust Quantum Sensors program, which aims to facilitate the integration of these sensors into DOD platforms. I am optimistic that these obstacles can be overcome. Boeing recently reported a successful flight test of a quantum IMU made by AOSense, a company participating in TQS.

Defend against the attacks of the future—today

The Biden administration made quantum computing and post-quantum encryption a national priority in 2022 with National Security Memorandum 10. In August 2024, NIST released three encryption standards, eight years in the making, that are resilient against classical and quantum computers. NIST encourages public and private entities to start transitioning to “post-quantum” algorithms now to protect long-term sensitive data from a future decryption attack (i.e., “harvest now, decrypt later”). There is time to make these changes. As RSA Security, the company behind the prime-number algorithm that secures most data today, points out, if quantum computers get close to cracking the commonly used 2048-bit keys of today, 4096-bit keys are already supported. These changes come with costs, and the willingness to bear these costs now forces you to assess your belief in the viability of scalable quantum computing within the timeframe of the sensitivity of your data.

Expand the application of AI in science

The 2024 Nobel Prize awards shocked the scientific community with the physics and chemistry prizes recognizing achievements in AI and machine learning applied to physical problems. The chemistry prize recognized Demis Hassabis and John Jumper from Google DeepMind (London) for their AI model AlphaFold 2, which predicts the three-dimensional structure of proteins based on the amino acid sequence, demonstrating that some of the touted applications of quantum computing don’t require one. Their model learned from the experimentally-determined protein structures found in the Protein Data Bank and now predicts the structure of almost all known proteins (about 200 million)—all without trying to solve the complex equations that govern atomic and molecular interactions.

Many other interesting problems in chemistry and material science can likely be tackled by creative applications of AI, leaving a smaller but still significant subset of problems to quantum computing. There is still work to be done to define what classes of problems lend themselves to AI solutions and are too difficult for classical computing. While it may be hoping for too much to repeat the success of AlphaFold 2, further discoveries may solve more problems before a quantum computer gets a chance to.

Final thoughts

The back-and-forth between quantum skeptics and optimists is decades old. Quantum computers exist today and have some limited commercial uses, defying the expectations of early critics. Yet, quantum computing’s anticipated promise seems perpetually out of reach, with daunting error correction as the new hurdle to clear. The estimate of 10 to 15 years for a useful quantum computer is both pessimistic and optimistic at the same time, not unlike a qubit. DARPA’s QBI will help clarify this estimate in the coming years. There is even a chance that it might swing the momentum solidly in favor of the quantum computing optimists by making the case for a moonshot. A valuable, albeit less decisive, outcome will be a better understanding of the engineering challenges of scaling up quantum processing.

In the meantime, the U.S. government, academia, and industry should step up efforts to expand the quantum workforce. Promising, while not being as risky as quantum computing, are new quantum sensors. Quantum inertial sensors, in particular, could be used on aircraft and spacecraft. Hopefully, a Nobel Prize is enough to recommend further efforts to use AI to solve problems in quantum science. Finally, if you tend to be a quantum computing optimist, like me, then you can also plan for post-quantum cryptography now by implementing new encryption standards.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. government or the Department of Defense.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).