In the year after the presidential elections, two states and one big city move to the center of American politics. Most states elect their governors in even years. Virginia and New Jersey elect theirs the year after the presidential vote. New York City chooses its mayor on the same schedule.

For decades, politicians and election analysts have looked to these contests for clues as to what will happen in the midterm elections a year hence, and 2025 is no exception.

The results in Virginia, New Jersey, and New York will not have a direct effect on the 2026 results, but a large impact on punditry, expectations, the strategies of both parties, and the decisions of potential candidates to run next year or not.

So it’s worth exploring how closely the results in the three states matched what happened a year later. What does history tell us about how indicative these outcomes will be?

Occasionally, they are prophetic; often, not so much.

Distinct places, distinct histories, distinct politics

One reason for the mixed predictive record of the three jurisdictions is that they differ significantly from one another. Virginia is on a long political journey from being a quite reliable Republican state—it was the only southern state that Georgia’s Jimmy Carter lost in 1976—to being a purple state and now, a fairly blue one. It is also more reactive to the previous year’s presidential result than either New York or New Jersey. Republican pollster Whit Ayres notes that the party that won the White House the year before lost the Virginia governorship in 11 of the 12 contests since 1977. Only Democrat Terry McAuliffe bucked this trend in 2013, after President Barack Obama’s reelection. Virginia is also unusual because it does not allow its governors to run for a second consecutive term. So every race is a fresh contest.

New Jersey is a more reliably Democratic state, though it is being closely watched this year because it was one among a number of blue states that, while backing former Vice President Kamala Harris, swung hard toward Donald Trump in 2024. In 2020, Joe Biden carried New Jersey by 15.9 percentage points; Harris won it by just 5.9.

New York City is a paradox. It is a Democratic bastion that nonetheless elected Republican candidates for Mayor in five consecutive elections between 1993 and 2009. (In the fifth of those, in 2009, Mayor Michael Bloomberg ran on the Republican ticket but had changed his party registration to Independent two years earlier.)

New York City is also one of the few places in the country with a version of a multi-party system and fusion voting—meaning that two parties can endorse the same candidate and have votes on separate party lines merged. These days, this means that the state’s Conservative Party usually (but not always) endorses the Republican nominee, and the pro-labor Working Families usually (but not always) endorses the Democrat.

New York’s multi-party system often turns mayoral races into contests between a Democrat and a third-party candidate—who is frequently a registered Democrat—while the Republican nominee plays a minor role. This happened in 1977 when future Governor Mario Cuomo lost the Democratic nomination to Representative Ed Koch but opposed him in November on the now-defunct Liberal Party line; Koch won 50% to 41%—meaning more than nine out of ten voters chose one of the two Democrats.

This year, polls show that the leading opponent of Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani is also a third-party candidate—and a Democrat. He happens to be Mario Cuomo’s son, Andrew Cuomo, the former Governor who, like his father, lost the Democratic primary.

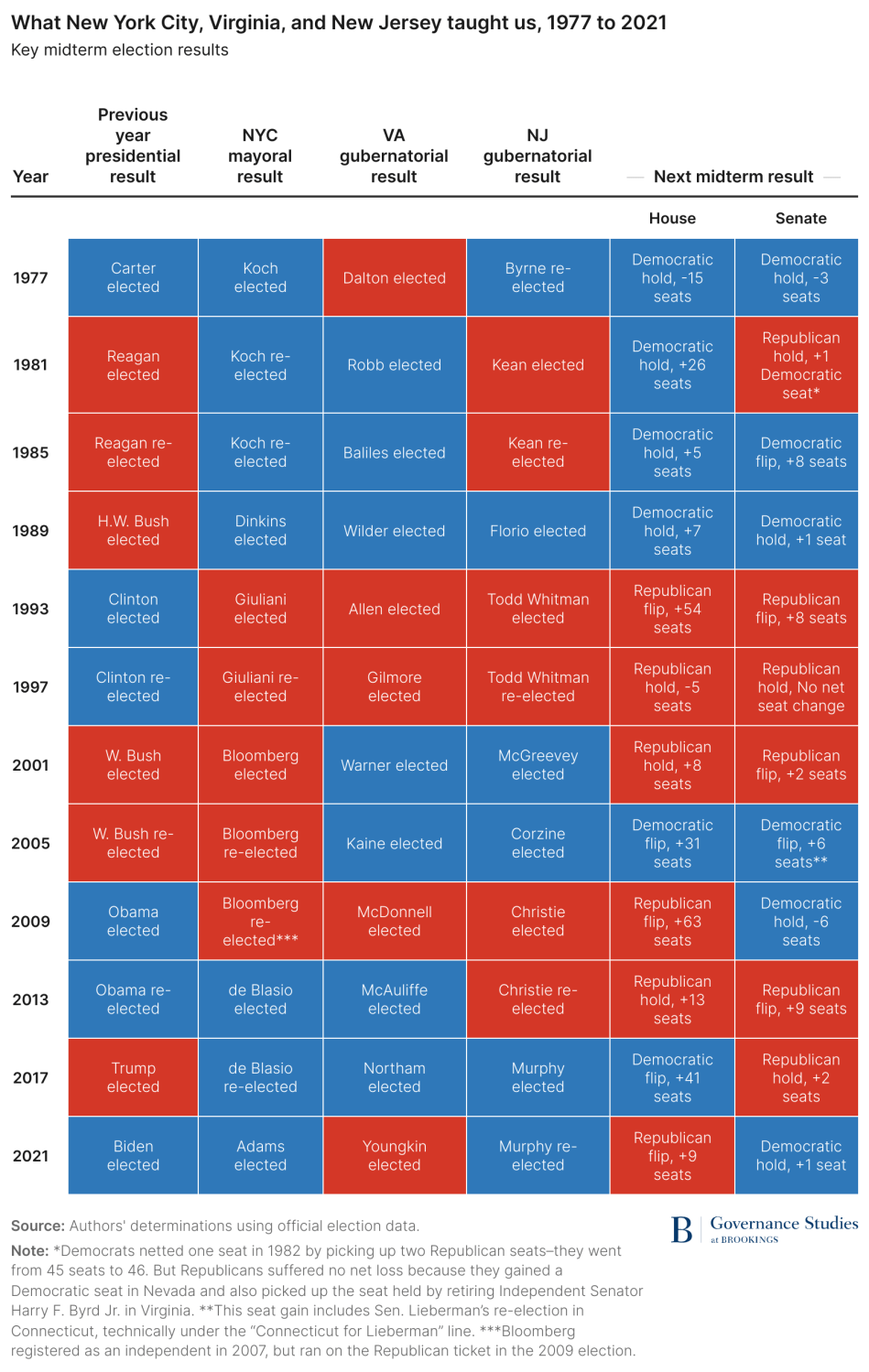

Given the differences among them, it’s no wonder—as the accompanying table shows—that in only five of the 12 election cycles between 1977 and 2021 has one party swept all three contests. Republicans did it three times, Democrats twice.

In all five cases, the sweeps were indicative of what would happen in the next year’s midterms, but not to the same degree.

Lessons from 5 sweeps

The Republican sweep in 1993 during President Bill Clinton’s first year in office might be seen as the most predictive of all these elections. The victories of Rudy Giuliani in New York City, Christine Todd Whitman in New Jersey, and George Allen in Virginia heralded the Republican Revolution of 1994. The GOP gained 54 seats, seizing control of the House for the first time since the 1952 elections, while also taking control of the Senate with an eight-seat pickup.

In 2009, the year after Obama’s first election, Republicans won another sweep that heralded change the next year. Michael Bloomberg was reelected as mayor of New York, Chris Christie was elected as governor of New Jersey, and Bob McDonnell won Virginia’s governorship by a large margin. This GOP sweep presaged another House landslide for the party—Republicans picked up 63 seats—another shift in party control. The Republicans also gained six seats in the Senate, but this was not enough to overturn a very large pre-election Democratic majority.

By contrast, the 1997 Republican sweep after Clinton’s reelection—Rudy Giuliani and Christine Todd Whitman won second terms while Republican Jim Gilmore prevailed in Virginia—was only weakly linked to the 1998 outcome. True, Republicans held on to both the House and the Senate. But Democrats actually gained five seats in the House—highly unusual for the party in the White House—partly because the GOP’s impeachment effort against Clinton was unpopular at the time and created an anti-Republican backlash. There was no net shift in Senate seats.

The Democrats’ 2017 sweep after President Trump’s first election—Ralph Northam’s victory in Virginia, Phil Murphy’s election in New Jersey, and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s reelection in New York City—could be seen as an indicator of the large 2018 gains to come in House races. The Democrats’ 41-seat pickup returned them to control of the House, which they had lost in 2010. The Senate moved in a different direction; Republicans gained two seats and maintained control because of a very favorable electoral map for the GOP in the states with contests that year.

The other Democratic three-state sweep came in 1989 during President George H.W. Bush’s first year in office. David Dinkins was elected mayor of New York, and Democrats captured the governor’s offices in Virginia with Doug Wilder and in New Jersey with James Florio. The election was historically significant, since Dinkins was New York City’s first Black mayor while Wilder was the first Black governor of Virginia. Even though Democratic performance was consistent with the 1990 election result, the party made no large-scale gains. The Democrats retained control of both houses, but picked up only seven House seats and a single seat in the Senate.

The fact that these sweeps were, on the whole, more closely connected to House than Senate results offers a potentially important lesson for next year. House outcomes are truly national in scope. But only a third of the Senate is on the ballot in any given election, meaning that the outcome hangs a great deal on which states are at stake. Even Democrats agree that the 2026 Senate map is challenging for their party.

When New Jersey, Virginia, and New York City split

The seven cycles with mixed results present, not surprisingly, a very mixed picture. They also underscore how local circumstances and the strengths of individual candidates can muddle partisan trends.

In both the 1981 and 1985 elections during President Ronald Reagan’s administration, Democrats won the New York mayoralty and the Virginia governorship, but lost New Jersey’s governorship. Koch was reelected twice while Democrats won back-to-back victories in Virginia, under Chuck Robb in 1981 and Gerald Baliles in 1985. But Republicans prevailed in New Jersey with the election and reelection of popular Republican moderate Tom Kean. He won in 1981 by only 1,797 votes out of more than 2 million cast over U.S. Representative incumbent Jim Florio, but was reelected four years later in a landslide. (Florio would come back to win the governorship in 1989 after Kean’s two terms in office.)

What followed? In 1982, Democrats maintained their control of the House and gained 26 seats—the product of a sharp economic contraction. The Senate races, however, were essentially a wash. Democrats picked up two Republican seats, but Republicans picked up a Democratic seat plus the seat of the retiring Independent senator in Virginia, Harry F. Byrd Jr. In 1986, Democrats sharply rolled back Reagan Era GOP gains. Democrats took back control of the Senate with a gain of eight seats while maintaining their House majority with a pickup of five.

In 2001 and 2005, Republicans won the New York City mayoralty but lost both the Virginia and New Jersey governorships. These were sui generis years because New York City Mayor Bloomberg was a sui generis politician—essentially a moderate Democrat (he would seek the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination) who briefly donned Republican clothing.

The two Democratic victories in 2001—Mark Warner’s in Virginia and Jim McGreevey’s in New Jersey—said nothing at all about the 2002 elections, which produced Republican gains after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks sent President George W. Bush’s popularity soaring. But the Democratic victories of Tim Kaine in Virginia and Jon Corzine in New Jersey in 2005 did give some indication of what was to come: The Democrats swept the 2006 midterms, taking over both the House and the Senate. Bush famously called the election a “thumping” for his party. In Virginia, the two elections also had long-term implications for the political trajectories of Warner and Kaine. Both are now U.S. senators.

The Terry McAuliffe victory for the Democrats in Virginia in 2013, after Obama’s 2012 win, already marks the year as singular. Democrat Bill de Blasio won his initial race for Mayor of New York, while New Jersey’s Republican Governor Chris Christie was reelected in New Jersey. Christie’s triumph was the most indicative result for 2014, which saw the Republicans holding the House with a gain of 13 seats and sweeping to control of the Senate with a nine-seat pickup.

The lesson here—which gives pundits a lot of room for maneuver—is that a single contest among the three can prove far more significant for the future than the others. This was also the case in 2021, after President Biden’s victory over Trump. Republican Glenn Youngkin won in Virginia and foiled McAuliffe’s comeback effort, even as Democrat Eric Adams prevailed in New York City and Democrat Phil Murphy was reelected as governor of New Jersey.

Youngkin’s victory reflected lingering discontent in the wake of the pandemic, particularly parental frustration with how public schools handled shutdowns. It signaled a post-pandemic distemper that would help pave the way for Trump’s comeback. McAuliffe also faced headwinds from President Biden’s approval rating, which stood at 42% in November in Gallup polling, the lowest of his presidency at that point. Another sign of trouble for Democrats came in New Jersey, where Murphy, once considered a heavy favorite by pundits, narrowly defeated Republican Jack Ciattarelli 51.2% to 48%. Adams’ victory offered a similarly mixed message: Although a Democrat, he secured his party’s primary as the most conservative candidate in the race.

Yet 2021 proved to be more predictive of Democratic challenges after the 2022 midterms than in those races themselves. The Republicans did flip the House in their favor, but gained only nine seats. Democrats surpassed expectations by holding the Senate with a gain of one seat. The intervening event was the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Backlash against the conservative Court was near its height on Election Day 2022 and blocked the typical midterm recoil from an incumbent president’s party. But by 2024, the impact of the abortion issue had faded in comparison with other questions, notably prices and immigration.

The award for the least prophetic Virginia-New Jersey-New York City cycle of the last half century might well go to 1977, the year after President Jimmy Carter was elected. Democrat Koch won in New York City in his contest with Cuomo, Democrat Brendan Byrne prevailed in New Jersey, while Republican John M. Dalton defeated Democrat Henry Howell, a legendary populist voice, in Virginia. The subsequent 1978 midterms saw the Democrats suffering modest losses while maintaining control of both the House and Senate.

In retrospect, the 1978 defeats of five incumbent Democratic senators, in most cases by Republicans representing a rising conservative movement, can be seen as portents of the Reagan Revolution of 1980. But that future was certainly not visible in the 1977 results.

How to judge this November’s outcomes

This November’s voting will be unusual because one choice voters will be making will have a direct effect on each party’s chances of winning control of the federal House of Representatives. California’s electorate will decide on a proposition that would set aside the current congressional district lines approved by a nonpartisan commission and replace them with a new map that would give the Democrats a good chance of picking up five additional House seats.

Proposition 50, as it’s known, was put on the ballot by Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom and the Democratic-led legislature in reaction to an unusual midterm redistricting undertaken by Republicans who control the state government in Texas at the behest of Trump. The new GOP map in Texas is projected to give the party—yes—five more seats. Other Republican states may try to use mapmaking to add to the party’s advantage. A victory for the Democrats’ new congressional map in California would largely offset the fruits of Republican district line-changing elsewhere.

It will be an expensive contest, and it could be tight. While California’s strongly Democratic leanings suggest the new district lines could prevail, many voters like the state’s existing nonpartisan system. Democrats will thus make the choice about Trump, Republicans about preserving the commission system. Conscious of this, the Democratic ballot proposal explicitly returns line-drawing to the nonpartisan commission after the 2030 Census—and, presumably, after Trump is out of office.

When it comes to the two states and New York City, current polling suggests that Democrats have a strong chance of sweeping all of them.

In Virginia, former Democratic Representative Abigail Spanberger has consistently led Republican Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears, with margins of around eight points. Democrats are hoping that a big Spanberger victory could help them pick up seats in the state legislature, which they currently control by narrow margins. While not conceding the governorship outright, Republicans have signaled that they are trying to salvage what they can by investing heavily in GOP Attorney General Jason Miyares’ race for attorney general against former Democratic legislator Jay Jones. Spanberger has run explicitly against Trump’s policies, particularly federal government layoffs and firings deeply unpopular in the state that, just after California, has the largest number of federal employees in the nation.

In New Jersey, Democratic Representative Mikie Sherrill (who was Spanberger’s roommate when both served in Congress and shares her national security background) has held leads comparable to Spanberger’s over Republican Jack Ciattarelli, though a few surveys showed the race closer. The contest has been shaken by the improper release of a mostly unredacted version of Sherrill’s military records by the National Archives to a Ciattarelli ally. Ciattarelli is generally given a better chance than Earle-Sears, partly because Democrats under Governor Murphy have held power in New Jersey for eight years and also because of New Jersey’s swing toward the GOP in 2024.

Victories by both Spanberger and Sherrill would inevitably be seen as a blow to Trump, given how both candidates explicitly chose to mobilize anti-Trump sentiment in their respective states. A representative ad from Sherrill begins: “MAGA’s coming for New Jersey with Trump-endorsed Republican Jack Ciatterilli.” Their victories would be put in the context of broadly declining Trump approval ratings. Especially if both win by substantial margins, a Democratic Party that has seen its own favorability decline in post-2024 polls would tout two moderate, experienced women as representatives of a new generation—Spanberger is 46, Sherrill, 53—that is in a strong position to refurbish the party’s image.

Precisely because Spanberger and Sherrill are generally favored, a win by either Republican in a state that voted for Harris would be cast by Trump and his party as a sign of the president’s enduring political strength and the Democrats’ ongoing malaise. At this point, just one close contest, let alone two—or even a GOP victory in the highly contested Virginia attorney general’s race—would come as a relief for the GOP.

True to history, the New York City mayoral race defies easy partisan categorization. Until late September, it was a four-cornered contest that seemed destined to ensure Mamdani’s victory. Besides Mamdani and Cuomo, the race included Mayor Adams, a deeply unpopular incumbent running on a third-party ticket, and Republican Curtis Sliwa, who lost four years ago.

Polling suggests that among Mamdani’s main challengers, Cuomo has been the only one with a chance to defeat Mamdani, but he had been bleeding votes to both Sliwa and Adams. Adams’ decision to withdraw from the race on September 28 is likely to give Cuomo a bump, but a modest one, given how poorly Adams was performing in the polls. Cuomo’s only path to victory is to persuade voters that they are facing what is essentially a two-person contest and to consolidate support among voters who see Mamdani as too left-wing. Even this might not be enough, given Cuomo’s lingering unpopularity and Mamdani’s emergence as a charismatic, upbeat voice.

In principle, a victory by either Mamdani or Cuomo would amount to the victory of a Democrat, and the race would likely be interpreted less in party terms than as a reflection of voters’ personal judgements about Mamdani and Cuomo and a test of strength between the Democrats’ left and centrist wings. If Mamdani wins, Republicans, including Trump, have already signaled that they intend to hang Mamdani’s most left-wing positions around Democrats running in 2026, particularly in suburban New York congressional districts the GOP is trying to hold. But history suggests that Americans outside the Empire State only rarely pay attention to a New York City mayor. In the meantime, progressives are already pointing to the possibilities of a new era of urban progressive governance, exemplified by Mamdani and Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, who will be unopposed for reelection in November. Her main opponent, businessman Josh Kraft, dropped out after Wu overwhelmed him, 72% to 23%, in the preliminary round of voting in early September.

Often lost in the contrast between the progressivism of Mamdani and the moderation of Spanberger and Sherrill is the fact that all three organized their campaigns around voter reaction to high prices. If they all prevail, their victories could signal that the cost of living—so crucial in driving Trump’s election—has now turned into a liability for the president.

History counsels intellectual humility in judging the staying power of all the analytical forays these elections will inspire. Their central virtue: Unlike predictions based on polls or political instinct, they reflect actual voters making actual choices at the ballot box.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What this fall’s elections can—and can’t—teach us about the midterms

October 2, 2025