The collapse of the shah’s government in Iran in early 1979 impacted the entire world but no country was more affected than Iraq. Saddam Hussein’s regime was the shah’s deadly enemy and had hosted the Ayatollah Khomeini in exile for years, but Saddam became the top foreign target of the revolutionaries in Tehran once they took power. Many countries were caught off balance by the Iranian revolution but none got it as wrong as Iraq. Its response—war—led to decades of conflict which have yet to end.

Ayatollah Khomeini was sent into exile in Turkey by the shah in 1964 for his role in leading protests against Iran’s close relations with the United States. In October 1965, Khomeini moved to Iraq to the Shia holy city of Najaf. The Iraqi government had a bitterly disputed border with Iran. The two governments were on the opposite sides of the Cold War: Iraq was the beneficiary of large-scale Soviet military assistance.

The United States had built its Middle East policy around Iran and the shah. He was the anchor of the American posture in the Persian Gulf. Billions of dollars in arms went to the shah’s army. His downfall was a disaster in the minds of most Americans.

The United States had no relations with Iraq. It was a challenging intelligence target. The Iranians under the shah were quick to tell the Americans what they thought was going on inside Iraq: Its assessments were often way of the mark.

The Iraqi intelligence services helped Khomeini run a clandestine subversion operation from Najaf against the shah. The Iranian Shiite pilgrimage to Najaf was a useful cover for communicating with operatives inside Iran. Cassette tapes of Khomeini’s preaching were smuggled into Iran from Najaf.

In 1968 Saddam Hussein came to power in a coup. For the next decade he ruled Iraq behind the scenes. Saddam continued using Khomeini against the shah. For his part the shah backed a Kurdish insurgency against Saddam with the support of the CIA. Then in 1975, Saddam and the shah signed a peace agreement in Algiers which awarded Iran disputed territory along the Shatt al Arab in return for abandoning the Kurds.

In 1968 Saddam Hussein came to power in a coup. For the next decade he ruled Iraq behind the scenes. Saddam continued using Khomeini against the shah. For his part the shah backed a Kurdish insurgency against Saddam with the support of the CIA. Then in 1975, Saddam and the shah signed a peace agreement in Algiers which awarded Iran disputed territory along the Shatt al Arab in return for abandoning the Kurds.

Saddam did not abandon Khomeini along with the Kurds and he remained at the center of Islamic militancy against the shah right up to the start of the revolution. I was assigned to the Iran desk in the CIA in November 1978 amidst widespread allegations that the intelligence community had failed to anticipate the revolution.

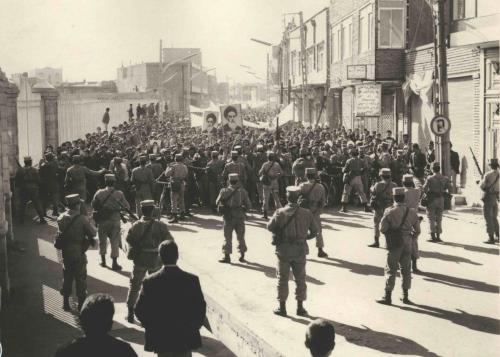

Whatever the failing of America’s intelligence, the Iraqis had clearly not anticipated the strength and magnitude of the revolution that they had helped create by supporting Khomeini for years in Najaf. On October 5, 1978, Saddam expelled Khomeini from Najaf. The Ayatollah found new refuge in France outside of Paris. From Neuphale Le Chataeu, Khomeini commanded the final months of the revolution and triumphantly returned to Tehran on February 1, 1979. Saddam alienated the man who had been laboring for years against the shah just before the moment of his triumph. It was a monumental mistake.

Within weeks of the creation of the Islamic Republic Khomeini reverse engineered the smuggling routes he had used against the shah from Najaf to now try to subvert Saddam’s Ba’athist regime in Baghdad. At the CIA, we forecast in the spring of 1979 that Iran-Iraq relations were heading toward conflict. The new revolutionary regime in Tehran began sponsoring a wave of terror attacks inside Iraq aimed at toppling Saddam and creating a second Islamic (and Shiite) Republic in Baghdad. Border clashes became normal.

Saddam was determined to fight back. He invited disgruntled generals from the shah’s former army to Baghdad to arrange a coup to oust the Ayatollah. Both sides engaged in conspiracies and plots to subvert the other. Both sides also targeted minority communities in the other for subversion: Iran worked on the Kurds, Iraq on the Arabs in Khuzistan and the Baluchis.

After the seizure of the American embassy in Tehran the CIA Task Force on Iran redoubled efforts to monitor the Iran-Iraq border for signs of a coming war. Among the generals who were assisting the Iraqis was Gholam Ali Oveissi, who had been the shah’s last army commander. He left Iran in January 1979 for exile in Paris. He continued to have close contacts with the American military that had developed during his years with the shah. Oveissi trained in the United States in Virginia and Kansas.

In September 1980 Oveissi came to New York and I debriefed him. He had just been in Baghdad and seen Saddam. War was imminent, according to what he had been told. The Iraqi army was poised to invade. Oveissi promised Saddam that Iran was weak and its military in disarray. Of course that is what Saddam wanted to hear.

The intelligence community issued an immediate warning memo indicating that the Iraqis were going to invade and assessing the implications. The memo concluded that Iraq was not likely to win a quick and cheap war. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brezezinski summed it up crisply: “Iraq has bitten off more than it can chew” he wrote to President Jimmy Carter.

Oveissi was assassinated in Paris on February 7, 1984 by an Iranian hit team. The war lasted eight years and cost the lives of a half million people, another million injured and over a trillion dollars in damage. It set in motion the march of folly that led to three more wars. It all began with Saddam’s mistakes in 1978 and 1979.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What Iran’s revolution meant for Iraq

January 24, 2019