This week, the United States Supreme Court will open one of the most consequential and controversial terms in recent memory. At stake are cases involving divisive issues such as guns and affirmative action. But by far the most contentious case will be an abortion case out of Mississippi. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is about a law that states abortions cannot take place after 15 weeks of pregnancy. It makes exceptions only for the life of the mother and for fetal abnormalities; none for rape or incest. The law effectively guts the “viability” criteria for abortion that has been in place ever since Roe v. Wade was decided a half century ago.

The Dobbs case was struck down in the lower courts. But the fact that the Supreme Court agreed to take it up—soon after the court allowed another restrictive abortion law out of Texas to go into effect—is the first serious indication in a long time that the landmark law making abortion a right could actually be reversed. The new, pro-life trio of justices—Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh, all appointed by President Trump—could easily be joined by Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas in forming a majority on the court.

At that point, the abortion issue will come roaring back into the political arena, and what happens next is anyone’s guess.

Abortion became a hot-button political issue in 1972. In President Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign, he was able to mobilize the Catholic vote using a range of cultural issues, including abortion. When he ran against then-Sen. John Kennedy in 1960, he won only 22% of the Catholic vote; by 1968, he won 33% of the vote. But in 1972, Republicans turned Democratic Sen. George McGovern into the candidate of “acid, abortion and amnesty,” and the label stuck. Eleven months after the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v Wade, Nixon won more than 50% of the Catholic vote, and the Republican Party became the anti-abortion party. Their next president, Ronald Reagan, also adopted an anti-abortion stand. The base of the party had become so pro-life that in the 1980 campaign, candidate Reagan found himself apologizing to Republican primary voters for having signed a liberal California abortion law, arguing that the law had been subverted by medical professionals. Thirty-six years later, another Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, also found himself having to disavow his previous pro-abortion statements in favor of Republican orthodoxy.

Today, 59% of Americans agree with the statement that “Abortion should be legal in all or most cases.” Within those numbers, however, exists a sharp partisan divide. Most Republican voters are anti-abortion and most Democratic voters are pro-abortion as the following table shows. Over time, these trends have widened: The percentage of Republicans self-identified as “pro-life” increased from 51% in 1995 to 74% in 2021; the percentage of Democrats calling themselves “pro-choice” increased from 58% in 1995 to 70% in 2021. Women are somewhat more pro-choice than are men, and younger people are somewhat more pro-choice than older people—but none of these divides is as great as the partisan divide.

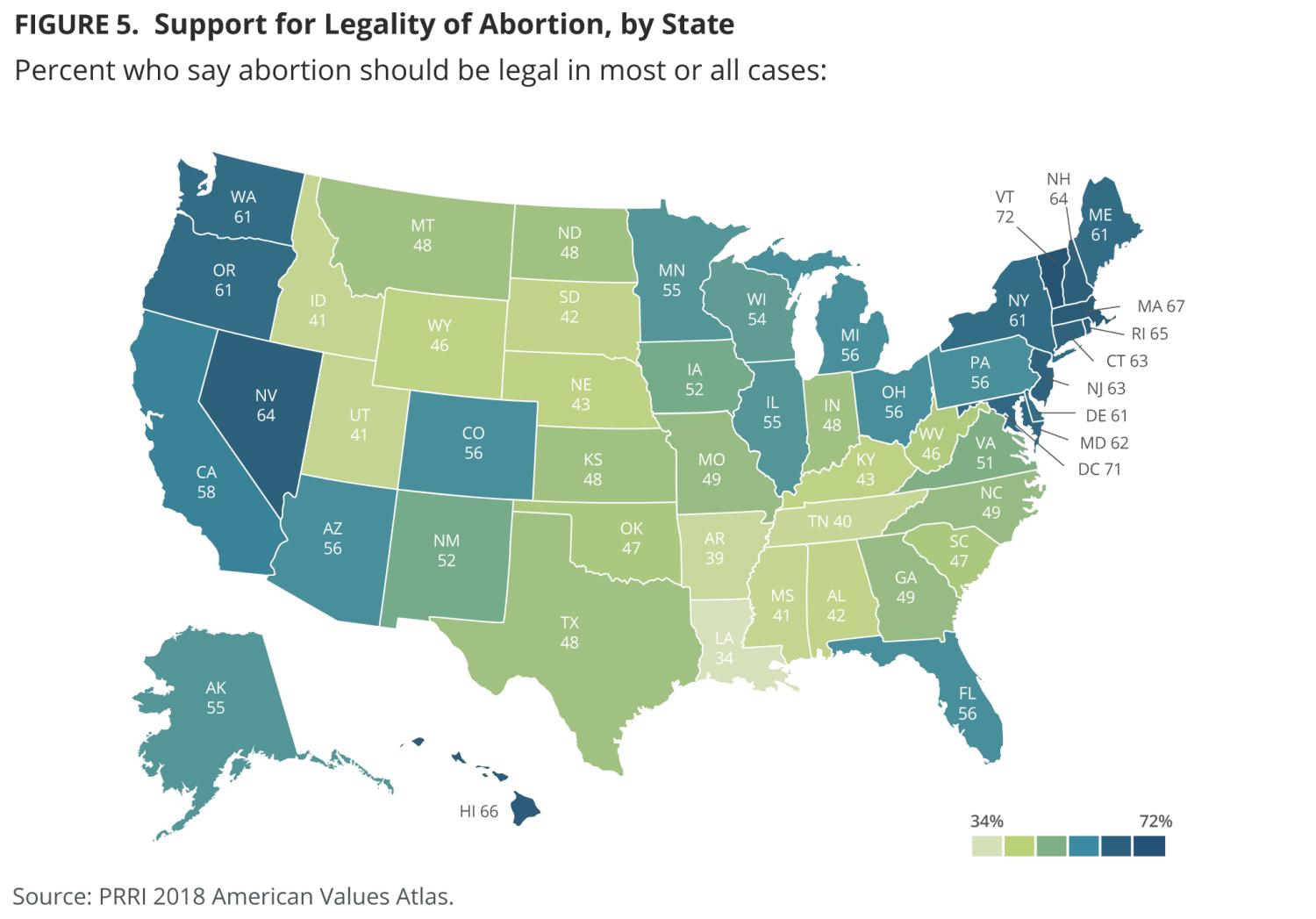

On top of the partisan divide is a regional divide. As the following map from PRRI indicates, attitudes vary significantly by region, with Southerners 12% less likely than the Northeasterners to say that abortion should be legal in most or all cases. If the Supreme Court reverses Roe, this map could well turn into a map that shows women where they will have to travel to in order to get an abortion (a situation guaranteed to favor the wealthy over the poor).

The politics of a post-Roe world

What are the politics of a post-Roe world? To even begin to predict this we need to ponder the importance of intensity in democratic systems. In Federalist #10, James Madison warned of the “mischiefs of faction”:

“By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.”

Scholars of democracy have grappled with this problem ever since. An impassioned majority can trample the rights of a minority as Madison feared. But an apathetic majority can lose to an impassioned minority, as the great political scientist Robert Dahl feared. So, where will the abortion debate go? This involves predicting the level of intensity. For most pro-life voters, abortion is a religious issue; for most pro-choice voters, it is a rights issue.

Here is what we can glean from public opinion data. Some polling indicates that, over time, abortion has become a more important consideration for voters. Gallup, for instance, found that, in 1992, only 13% of registered voters said a candidate must share their views on abortion to earn their vote. This number increased to 24% in 2020. These findings are more or less consistent with a Quinnipiac poll that asked, “If you agreed with a presidential candidate on other issues, but not on the issue of abortion, do you think you could still vote for that candidate or not?” A total of 69% of Republicans said yes and 62% of Democrats said yes.

Thus, in 2016, abortion seems to have been a motivator for about 31% of Republicans and 38% of Democrats. But it remains to be seen how numerous new laws seeking to restrict abortions—including the high-profile Texas law and, of course, the looming Supreme Court decision—will change attitudes and affect intensity. Some pollsters are finding an increased concern with the issue among Democratic women, and some analysts argue that Republicans should be worried about finally getting their way on this issue and unleashing a torrent of opposition. On the one hand, reversing Roe could awaken a sleeping giant of pro-choice voters. But, on the other hand, times have changed: Contraception is better; an out of wedlock birth no longer causes a woman to be cast out of society; and one of the two enormous generations in the electorate—the baby boomers—are all past the child-bearing age. These factors, if dominant, could mean an apathetic majority will allow a minority to dictate policy.

The whole notion of a national debate about abortion would, no doubt, blow James Madison’s 18th-century mind. But he was right about one thing: In the end, for better or for worse, passion and intensity still matter in politics.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What if the Supreme Court reverses Roe v. Wade?

October 5, 2021