AGOA has officially expired: What comes next?

Adopted in May 2000, the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has given dozens of African countries duty-free access to the U.S. market for more than 1,800 products. It has also promoted U.S. investment in Africa and encouraged African governments to implement economic and political reforms adapted to their contexts. According to the U.S. Trade Representative data, in 2024, Africa’s exports to the U.S. under AGOA were almost $10 billion. While its mandate has been extended several times, on September 30, 2025, AGOA officially expired; marking the end of nearly a quarter of century of U.S.-Africa trade relations and raising serious questions for African exporters, investors, and governments about the way forward.

This turning point comes at a pivotal moment: The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the largest trade project since the creation of the World Trade Organization, is gradually coming into full force and boosting intra-African trade. For many African countries, the foremost priority now lies in consolidating continental integration. However, some nations are electing to pursue bilateral agreements with Washington as a way forward (e.g., Kenya), reflecting a divergence in strategy on the continent. For these countries, the experience of Morocco—the only African country to have concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement with the United States—constitutes a valuable source of lessons.

Can bilateral free trade agreements stimulate African exports? Lessons from Morocco

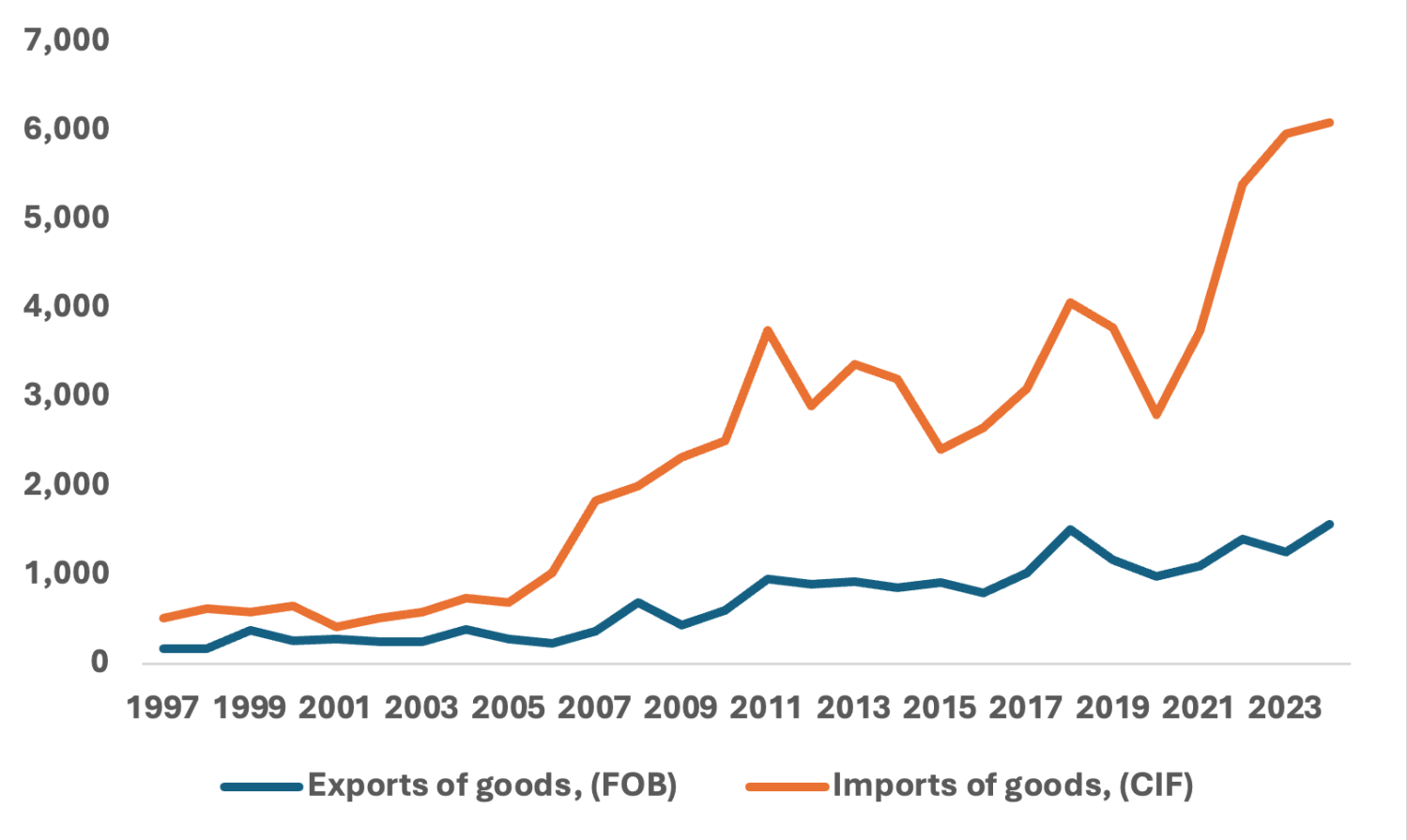

Signed in 2004 and having entered into force in 2006, the USMFTA aimed to make the Kingdom a regional platform for trade and investment, diversify its exports, attract U.S. direct investment, and stimulate employment. Covering goods, services, intellectual property, and investment protection, it was presented as a benchmark. However, nearly twenty years later, the results appear mixed: Imports from the U.S. have grown faster than exports, worsening Morocco’s trade balance (Figure 1). Moreover, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 2024, Morocco’s goods exports to the U.S. constituted only 3.1% of its total goods exports, in contrast to exports to the European Union (EU), which accounted for 65.3% of the total.

Figure 1. Morocco has experienced a persistent trade deficit with the United States since the USMFTA came into force in 2006 (in millions of current USD)

Under the USMFTA, the composition of Morocco’s goods exports to the U.S. has shifted away from female-intensive light manufacturing (textiles, apparel) and toward male-intensive, capital-heavy sectors (phosphatic fertilizers and other mineral or chemical fertilizers). This structural shift has contributed to Morocco’s low female labor force participation. American companies established in Morocco reinforce this trend, as they typically invest in capital-intensive sectors such as renewable energy, infrastructure, aviation or environmental technology. Moreover, the U.S. can benefit from trade flows between the EU-Morocco in these sectors, which are characterized by high male labor intensity. In addition to negatively impacting the female labor force in Morocco, the overall impact on the value-added composition of Morocco’s global goods exports has been mixed. In 2021, for example, the share of high-technology exports accounted for only 6% of total exports, slightly below their share in 2001.

Beyond these mixed economic results, other challenges have emerged. The asymmetry of commitments, with Morocco’s tariff reductions being much larger than those of the United States, and the limited export competitiveness of Morocco have made it difficult for the country to take full advantage of the agreement. In contrast, the U.S. has fully leveraged its much more competitive industrial base. According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative, the U.S. goods trade surplus with Morocco reached $3.4 billion in 2024, up from $35 million in 2005 (the last year before the treaty came into effect). Applying an augmented gravity model to Morocco’s exports to its 79 trading partners over the period 2004 through 2023, our recent paper, Koudjom et al. (2025) shows that the USMFTA has had an overall negative effect on Moroccan exports, including strategic sectors such as agri-food and automotive. These results demonstrate how structural and institutional asymmetries limit the ability of small economies to benefit from North-South bilateral trade agreements.

Vulnerability of the bilateral agreement has been further exacerbated by political uncertainties, especially the April 2025 decision of the second Donald Trump administration to impose a general 10% tariff on Morocco’s imports. This decision clearly contradicts Article 2.31 of the USMFTA.

Five recommendations for a post-AGOA future

With the AGOA having expired at the end of September 2025 and several African countries already facing heightened U.S. tariffs since early April, the Moroccan experience offers Africa three key lessons for navigating the new global trade landscape. First, bilateral free trade agreements that are characterized by strong power asymmetry as well as differences in development levels are likely to lead to unbalanced outcomes due to one-sided concessions and varied initial conditions. Second, preferential market access is not synonymous with competitiveness: It can only be exploited if countries have a solid productive base. Finally, bilateral agreements alone do not guarantee a structural transformation of economies. Africa thus finds itself at a strategic crossroads and needs to define a strategy that prioritizes regional integration and the strengthening of its productive capacities.

From this perspective, attempts to increase bilateral agreements between several countries including the U.S. as well as other developed (e.g., European Union and Japan) and emerging (e.g., China, Türkiye, South Korea among others) economies2 carries real risks for the continent: asymmetric obligations, fragmentation of rules of origin, and weakening of the regional cohesion fostered by the AfCFTA. On the other hand, by negotiating collectively, Africa could leverage its rising global economic weight, secure fair conditions, and align its external commitments with its priorities of value addition and intra-African trade.

It is well recognized that opportunities for intra-African trade remain largely underexploited. Morocco did not transform its free trade agreement with the U.S. into a springboard for its African integration. In contrast, the AfCFTA now offers countries on the continent a unique platform to build regional value chains across diverse sectors, ranging from agrifood to pharmaceuticals, while also enabling the entry into global value chains at higher levels. Future agreements with partners in the Global North should complement this momentum, not hinder it.

Five priorities stand out for Africa in developing a post-AGOA roadmap.

- Negotiating collectively with the United States,

- Keeping the AfCFTA at the heart of the continental strategy,

- Strengthening export and production competitiveness before relying on trade preferences,

- Prudently managing expectations regarding free trade agreements, and

- Fully seizing the potential of South-South trade.

The expiration of AGOA presents both risk and opportunity. Africa can either engage in a fragmented bilateral approach, at the risk of replicating the Moroccan experience on a large scale, or it can choose to consolidate its unity, speak with one voice, and demand that advanced economies approach the continent as an equal partner. The path chosen will have profound implications, not only for trade, but also for the future of the continent’s development and ultimately the global economy.

-

Footnotes

- “Neither Party may increase an existing customs duty or introduce a customs duty on an originating product”.

- For example, United States Trade Representative (USTR) continued negotiations for the Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership (STIP) with Kenya, launched in July 2022, aimed at stimulating investment, promoting sustainable and inclusive growth, supporting workers and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), while strengthening African regional economic integration.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

US-Africa trade at a crossroads: Lessons from Morocco’s US Free Trade Agreement as AGOA expires

November 21, 2025