For more from Africa in Focus, sign up for the blog RSS here, or connect with Brookings Global via email and social.

Dual Challenges: Human Suffering and the Economic Toll

Since March 2014, over 3,000 people have died from the relentless spread of the Ebola virus throughout the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria.

Despite the heroic efforts of the humanitarian and medical professionals in these countries, crumbling public health systems—which were notoriously weak even before the current outbreak began—and a lack of facilities, equipment and medical staff have tragically not been able to stem the tide in these countries. Distrust of the government—fueled by decades of civil war—has also prompted attacks on health workers by fearful groups, further undercutting crucial outreach and educational interventions aimed at sensitizing communities to the virus and breaking the chain of transmission.

Before the Ebola outbreak intensified, these countries were making remarkable economic progress—particularly Sierra Leone and Liberia, which experienced rapid economic growth in recent years after overcoming decades of civil strife. In 2013, Sierra Leone and Liberia ranked second and sixth among the top 10 countries with the highest GDP growth in the world (albeit their base levels of GDP are very small to begin with). Guinea, while growing more slowly at 2.5 percent in 2013, had high expectations for growth resting on its Simandou iron ore project, on to which international investors Chinalco, Rio Tinto, and the International Finance Corporation have signed. However, the iron mining sectors in these countries have been hit both by declining prices and the Ebola outbreak, calling into question the expected profitability of these projects, hurting investor confidence in the region and hindering contributions to future growth. At the beginning of the year, the International Monetary Fund forecasted that GDP growth in 2014 would amount to 11.3 percent, 5.9 percent and 4.5 percent for Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, respectively. In mid-August, as a result of these factors, the IMF revised these estimates to 8.0 percent, 2.5 percent and 2.4 percent, accordingly.

Economic Effects of the Outbreak

In addition to the enormous and tragic loss of human life, the Ebola epidemic is having devastating effects on these West African economies in a variety of essential sectors by halting trade, hurting agriculture and scaring investors.

Mobility restrictions, trade and transport: To halt the spread of the virus, the countries most affected by Ebola have implemented quarantines in areas where risk of infection is high while neighboring countries such as Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal have imposed restrictions on the movement of people and goods, including border closures. These measures, in turn, have reduced internal and regional trade, transport and, of course, tourism. But since official trade statistics do not capture informal trade—including cross-border trade which could range from 20 to 75 percent of GDP for West African countries—the estimated impact proposed by the World Bank may overlook the large reduction in informal trade due to mobility constraints. While these actions aim to break the chain of transmission, the president of Sierra Leone has called them an “economic blockade” that has resulted in scaled-back production and revenues for the government.

Agriculture: According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), agriculture accounts for 57 percent of Sierra Leone’s GDP, 39 percent of Liberia’s, 20 percent of Guinea’s, and 22 percent of Nigeria’s. Disruptions from the outbreak during the planting season earlier this year are expected to diminish yields for the staple crops of rice and maize during the harvest season, between October and December. Already, the price of the staple crop cassava in some places in Liberia has more than doubled (increased by 150 percent) according to the FAO. Food price shocks such as these will likely lead to inflation: According to IMF estimates, in Liberia the inflation rate will climb to 13.1 percent in 2014 from 7.7 percent before the Ebola crisis first broke.

Mining and investment: Mining activity (which constitutes 14 percent of Liberia’s economy and approximately 17 percent of Sierra Leone’s) is decreasing in Liberia and Sierra Leone following restrictions on non-essential travel and repatriation of personnel. Voice of America reports that investor confidence has dropped since the escalation of Ebola cases. China Union and Arcelor Mittal are scaling down iron ore mining operations in Liberia. Some miners in Sierra Leone and Liberia are afraid to enter high-risk districts, and several firms (including Australian mining firm Tawana Resources and Canadian Oversea Petroleum) have suspended operations or sent foreign workers home. Investments may be postponed and even cancelled if the perceived risks are too great. Guinea, for now, is not experiencing a major impact on its mining sector since its main mines are not located in the areas where there is a high risk of infection.

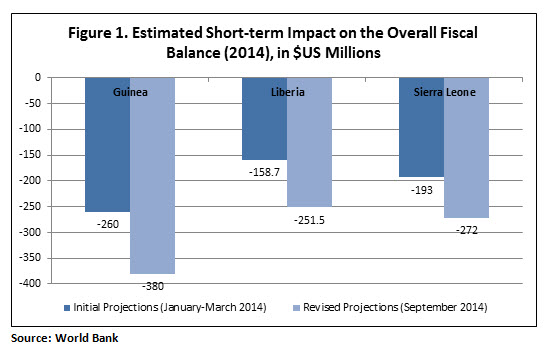

Fiscal challenges: Fiscal revenues will decline as limited economic activity reduces revenues from taxes, tariffs and customs duties. At the same time, to resolve the crisis and meet the greater health and security needs of their people, government expenditures will need to rise. Avoiding the impact on the poorest and most vulnerable will also necessitate more transfers. As seen in Figure 1, the World Bank reports that “short-term fiscal impacts are also large, at $93 million for Liberia (4.7 percent of GDP); $79 million for Sierra Leone (1.8 percent of GDP); and $120 million for Guinea (1.8 percent of GDP).”

The financial sector: Although the financial sector has largely been excluded from the narrative of the outbreak, it is worth noting that if large depositors withdraw funds, banks may face serious liquidity problems. Also, if some big creditors miss payments, the number of nonperforming loans will increase, eventually leading to some defaults. So liquidity management must also be a priority and banks’ bad loans portfolio need to be monitored carefully. Ultimately, loss of confidence in the financial system is the main risk factor and should be avoided. Finally, capital flight is an additional risk to the financial system especially as exchange rates have become more volatile. The World Bank reports that many wealthier Guineans and expatriates have already left the country and that uncertainty and risk aversion in Sierra Leone has prompted a rise in capital outflows.

Tourism: Airlines such as British Airways, Emirates, Air France, Asky Airlines and Arik Air have implemented some bans on flights to and from the most affected countries. The African Union has asked for these bans to be lifted and also for proper screening mechanisms to be put in place at airports. CEOs of 11 firms operating in West Africa have said that some measures, including these travel restrictions, are doing more harm than good and may well be contributing to the humanitarian crisis by blocking crucial trade flows, thereby pushing up the prices of essential foods and medicines. There are also some concerns that an indirect consequence of the Ebola outbreak will be diminished tourism throughout the African continent: As seen in another recent Africa in Focus blog, the Ebola outbreak has been dominating headlines in the U.S., African and international press since early August, even overshadowing the Africa Leaders Summit. Misconceptions about the transmission of Ebola and the risk of travel in Africa may further reduce tourism to and within the continent.

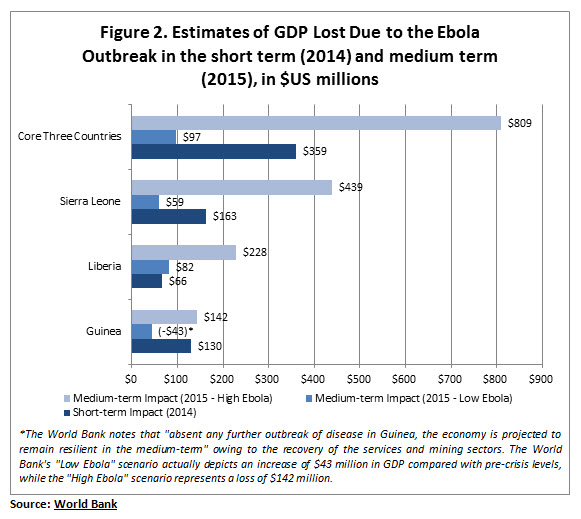

Fear of Contagion Curbs Economic Activity

What is striking about the Ebola outbreak’s effects on the economies of West Africa is that the most influential factor constraining economic activity there is fear. As stressed by the World Bank, “the largest economic effects of the crisis are not as a result of the direct costs (mortality, morbidity, caregiving, and associated losses to working days) but rather those resulting from aversion behavior driven by fear of contagion. This in turn leads to a fear of association with others and reduces labor force participation, closes places of employment, disrupts transportation, and motivates some government and private decision-makers to close sea ports and airports.” The World Bank also notes that behavioral effects were responsible for as much as 80 to 90 percent of the total economic impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic of 2002-2004 and the H1N1 flu epidemic of 2009. As the current epidemic continues to unfold, the World Bank estimates that economic activity could be drastically affected in both the short and medium term, depending on whether the outbreak is swiftly contained (a “Low Ebola” scenario) or the outbreak continues to spread apace (a “High Ebola” scenario) (Figure 2).

A Collective Response to a Global Threat

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently predicted that if the virus continues to spread at current rates, more than 1.4 million people will be infected before the outbreak is contained. But this prediction is a worst-case scenario that does not take into account recent efforts by the international community to stem the spread of the disease. It is, however, a stark reminder of the possible exponential transmission rate of the disease if the collective response to the Ebola threat is not fast and effective.

The U.N. has stated that $1 billion is needed to contain the Ebola outbreak, while the World Bank has estimated that containment and mitigation would require several billion dollars for humanitarian support, fiscal support, screening facilities at airports and seaports, and for strengthening the surveillance, detection and treatment capacity of health systems. The CDC has also emphasized the importance of building new medical facilities, improving home care treatment (including training thousands of health care workers), and implementing broad-based, effective public information campaigns. Although the CDC projected a sobering, worst-case scenario of 1.4 million cases of Ebola by January 2015 (from the 6,000 cases at the moment), it did not take into account the planned interventions by the international community—and recently, commitments to intervene have been made on a large scale.

International donors such as the World Bank and IMF have pledged to provide over $400 million and $130 million in financing (respectively) toward emergency response and medium- and long-term recovery in the most-affected countries. The U.S. has provided a surge of $175 million and 3,000 troops to help train nurses and establish emergency treatment facilities in Liberia. China has committed 174 doctors to Sierra Leone and $37 million in assistance to West Africa. Cuba has also pledged to provide the largest team of medical professionals of any country to assist the region, with 165 doctors set to arrive in Sierra Leone in October and an additional 296 heading to Guinea and Liberia.

African countries have made contributions in the fight against Ebola as well; for example, under the U.N. Mission for Emergency Ebola Response, Ghana will serve as a logistical and training hub for medical professionals in the region. Senegal is also helping set up an “air corridor” to facilitate the transportation of medical personnel to Ghana. Through the African Union Ebola Outbreak in West Africa (ASEOWA) mission, Uganda—a country that has dealt with Ebola crises in the past—has pledged 25 medical experts to advise regional efforts, as has the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) has given approximately $1 million to reinforce preventative measures aimed at stemming the spread of Ebola throughout West Africa. In addition, South Africa has established an Ebola diagnostics lab in Sierra Leone. While these commitments from international and regional donors show great promise to mitigate this crisis, only about one-third of the total $988 million requested by the U.N. has been pledged as of September 24, 2014.

Nevertheless, the considerable support from African countries and institutions, as well as the international community, highlights the growing recognition that Ebola is not a West African problem. It is not an African problem. It is a global problem that needs to be addressed at all levels (national, regional and international) as swiftly and completely as possible. In this sense, it is important to coordinate a united African and global response in the short term, but also consider how to integrate investment in health systems into regional development plans in the medium to long term so that public health crises like the current Ebola outbreak can be addressed more quickly (or averted entirely) in the future. The good news is that the people of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone are resilient and have surmounted terrible civil strife before, managing to establish new heights of political and macroeconomic stability in recent years. The same strength that allowed them to endure and rebuild from past devastating conflicts, in conjunction with international support, will help them overcome the Ebola outbreak now.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Understanding the Economic Effects of the 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa

October 1, 2014