“[T]he central paradox of financial crises is that what feels just and fair is the opposite of what’s required for a just and fair outcome.”

— Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner,

The New York Times, November 5, 2011

Sober analysis of the current stand-off over Ukraine tells us we are in a deep mess, worse than people tend to recognize. The events playing out now are bigger than Ukraine (even though, as we explain elsewhere, Ukraine is important to Russia). Both Russia and the West are deeply committed to broader objectives that seem fundamentally irreconcilable. There are no easy solutions to the crisis. Finding a way out is going to be long, costly, and messy, and the best final outcome is likely to feel unsatisfactory. In this regard, the remarks by Timothy Geithner quoted above are relevant. They are even more appropriate because Russia, through its current actions in Ukraine, has exposed the post-Cold War order in Europe as the geopolitical equivalent of a financial bubble. We have enjoyed two decades of benefits from this order. But we did so under the illusion that it was nearly costless. Now we are finding out that there is a bill to pay. To understand this metaphor, we need to examine how the crisis developed.

The Missing Quadrant

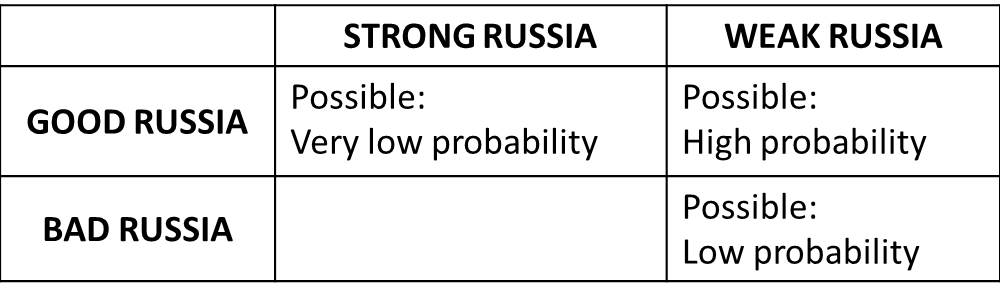

We can explain by using a simple framework that we first developed in 2008 after the Georgia crisis. Imagine a matrix with two columns, one labelled “Strong Russia” and the other “Weak Russia,” and two rows, one for “Good Russia” and the other for “Bad Russia.” Into the quadrants of this matrix we place the various “future Russias” as they were envisioned by most Western policymakers in the early 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The first possible Russia was one that would reform and succeed. That is, it would accept the so-called Washington consensus for economic reform and develop its democracy. This would result in a strong Russia that was positively inclined toward the West (that is, “good”). The second Russia would try to reform but never succeed. This Russia — a permanent “muddling through,” Yeltsin-ite Russia — would thus remain weak, but as long as it kept trying to be part of the West and following the U.S. lead, it would still be “good.” A third Russia would be one that rejected reforms altogether. It would also refuse to accept the U.S.-led post-Cold War international order (hence it would be “bad”), but since it didn’t reform it would remain weak and unable to follow through on any hostile intentions it might have. From the vantage point of the immediate post-Cold War period these, then, were the potential outcomes. Figure 1 illustrates the matrix, and into each quadrant we indicate how likely policymakers thought each outcome was.

Figure 1. The Russia Matrix and the Missing Quadrant

But note that there is one quadrant that is missing. What could not be imagined at all was the fourth alternative: a “strong, bad” Russia. Hence, no probability was attached to that outcome.

All this would have been rather academic except that the assumptions of this matrix were taken as the basis for the entire post-Cold War order. With the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Warsaw Pact, the United States took the lead in establishing a new international political order in Europe. The rallying cry was “a Europe whole and free.” The Iron Curtain separating West and East would be torn down, and the former Soviet republics and satellite nations of Eastern Europe would be transformed into Western-style market democracies as quickly as possible. As such, they could be incorporated into the new international order under the United States.

The problem was that reforming economies distorted by decades of the Soviet-style systems in Eastern Europe would be a wrenching process. Providing incentives for these countries to undertake the painful reforms necessary to make this new order happen required a big carrot. The carrot was membership in the premier Western clubs, the European Union and NATO. The promise of NATO membership was the key. No matter how much lip service the Eastern Europeans paid to the virtues of free markets, democracy, civil society, and so on, they took on the burdens of reform for one main reason: to earn a guarantee of protection against their age-old enemy, Russia.

At the time, and for years after, this appeared to be an unqualified foreign policy success for the United States. Had we not offered the incentive of NATO membership, it is likely that many, if not most, of the Eastern European countries would not have made nearly enough of the sacrifices needed for successful reform. Only the shared perception of the Russia threat could create domestic peace long enough to reform.

But what was not recognized was that this approach was based on a false assumption by the United States, namely that this perceived “Russia threat” was not real and never would be. Russia, we assumed, would remain more or less as it emerged from the Cold War, a backward, weak economy that would try, but most likely not be able, to follow the lead of its neighbors to the West and grow to become a strong market democracy. It would therefore slide further and further into weakness. A few optimists held to a fading hope that Russia might someday succeed in reform. No matter which way it went, Russia would not seriously threaten any country allied with the United States. It would either be “good” (if it reformed) or weak (if it didn’t). Neither of those Russias was a threat. The Russia that would be a threat — a strong, bad Russia — was unimaginable. This was precisely the “missing quadrant.”

The Insurance Scheme

When a particular bad outcome is unimaginable, there is little cost to selling insurance against this possibility. (Or, to use a different analogy, it is like selling a put option that is far out of the money — you claim the premium income, but nobody ever exercises the option.) In the minds of Russia’s neighbors who feared a resurgent Russia, the need for insurance was real, and they were eager to purchase the insurance. For them, there was no missing quadrant. For the U.S., which was convinced that Russia could only be either weak or good, it made sense to sell insurance. Promises of admission to NATO, even to Ukraine and Georgia, were perceived as low-cost, since the insurance contracts — that is, the commitment to protect the new NATO members against a serious Russian attack — would never be exercised. After all, that scenario assumed a Russia that was strong and bad, and that was impossible.

Now suppose that you are Vladimir Putin and you see the U.S. selling this insurance to all your neighbors. You do not have to be a genius to see the implications. One important consequence of any insurance is moral hazard. The insured party takes greater risks because it has insurance to fall back on. That is exactly what happened in the case of new NATO members, Poland and the Czech Republic, for instance. Barely three years after their admission into NATO, the two countries began lobbying to have American missile defense systems deployed on their soil — a move regarded by many Russians as a more serious threat to Russia’s security than NATO enlargement itself.

The moral hazard created by NATO expansion clearly made the international system more fragile. The United States is issuing all of these contingent liabilities, and if you are Putin, you want to indicate to the U.S. the cost of this. When repeated verbal protests do not suffice, as they clearly had not throughout the 1990s and then into the 2000s, the message has to be delivered in stronger fashion. Hence, the Georgia conflict of August 2008. Regardless of who started it, the conflict should have demonstrated with utmost clarity the cost of those insurance policies that the U.S. had been selling. The message was not received, however, much like the collapse of the subprime market should have foretold what was to come in the financial crisis. What we should have recognized — but few did — in the period between August 1998 and August 2008 was that the unimaginable had occurred. Russia had become strong, but “bad.” It had become strong again without “becoming like us.”

The Unthinkable

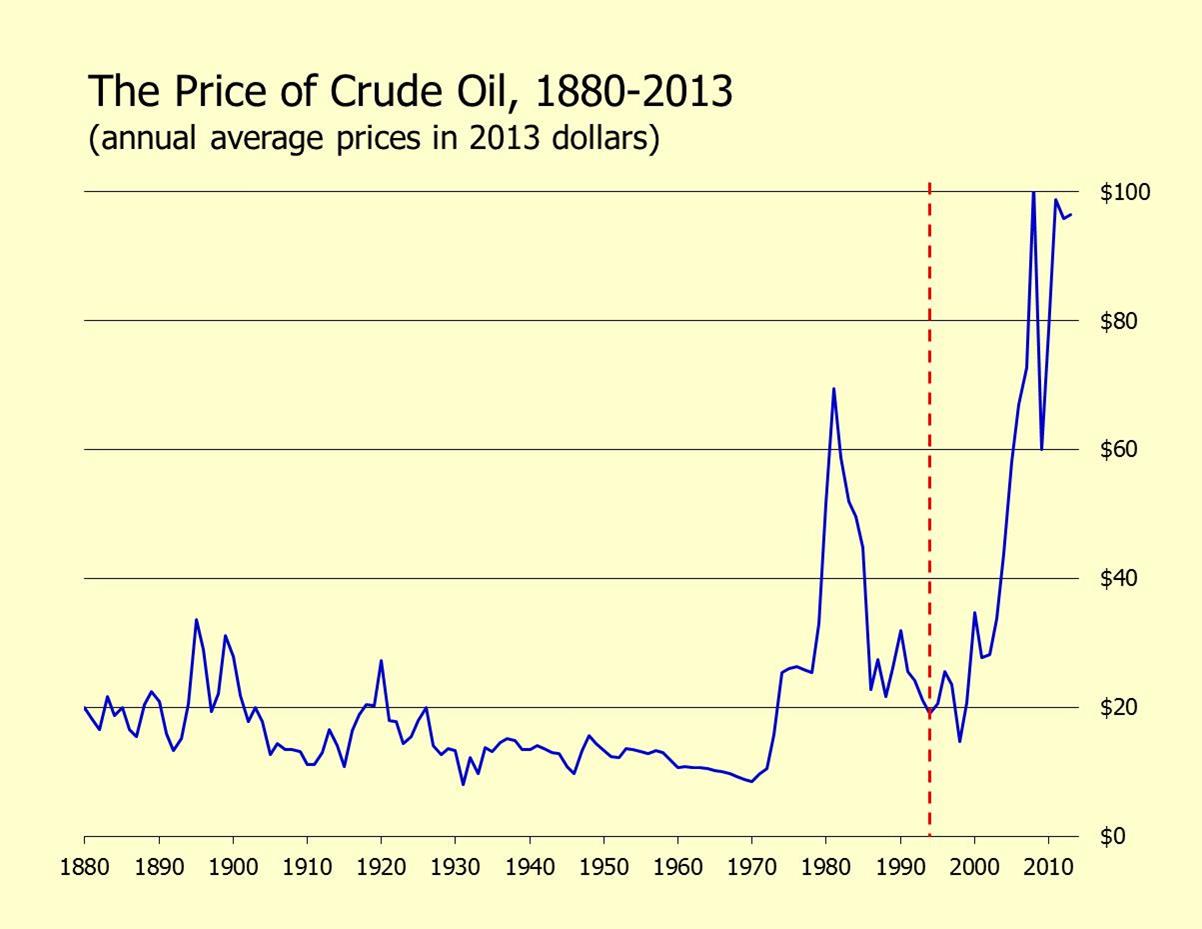

How exactly did that happen? The answer is oil. No one’s scenarios in the 1990s included one with a world oil price of $50 a barrel, much less $100-plus. And this is not just no one in the community of Russia analysts; not even the oil analysts thought that way. This was understandable. As Figure 2 shows, by the early 1990s the world oil price had been collapsing for more than a decade. From the vantage point of 1993, say, it was logical to think that the price spike of the late 1970s was a historical aberration, never to be repeated.

Figure 2. The World Oil Price, 1880-2013

Since no one could imagine $100 a barrel oil, no one thought of what kind of Russia we would have with $100 a barrel oil. That was like asking, what kind of Russia would we have if Martians took over the Kremlin? It was outside the realm of possibility.

But this also means that what had looked like a nearly riskless strategy for re-ordering a post-Cold War world and for assigning Russia a place in it turns out to have been a very risky one indeed. We built institutions on a fictitious foundation. We sold insurance policies like out of the money put options with no belief that the bubble would ever end. There was no push back for many years. We did get the benefit of that premium income — the Eastern Europeans embraced reform despite the difficulties, they remained at peace among themselves, and the U.S. could act freely in the global arena. Russia, and Yeltsin, had to comply. Russia was too weak to resist from the very beginning, and the weakness only grew over time. Between 1991 and 1999, Russia’s dollar GDP as a share of world GDP dropped by over 70 percent. In the two years from 1997 to 1999 alone, it collapsed by 50 percent. Meanwhile, the Russian government incurred close to $30 billion in new debt from 1996 to 1999.

The Bill Comes Due

Beneath the veneer of compliance and submission to the new world order, however, actual Russian attitudes about what was happening were very different. Again, as long as Russia was weak, what the Russians really thought did not matter. Once Russia’s capabilities later changed, those attitudes would be fateful. Nationalists and communists, of course, became even more deeply resentful of the U.S. as the end of the 1990s approached. But even pro-Western liberals were affected. Anatoly Chubais, the leading liberal reformer in Moscow working with the U.S., stated publicly already in 1997 that NATO enlargement was undercutting all attempts to reform Russia and bring it close to the West. The policy might bring short-term gain for the U.S., but it was bound to create a political backlash inside the country. It was a “major mistake,” Chubais said. The international order was thus analogous to a financial bubble. Chubais was simply warning that Western policy was creating a balloon payment that would come due in the future.

There was an attempt to rationalize what was going on to avoid recognition that Russia’s compliance was just Russian weakness. Proponents of NATO expansion saw this policy as a means to stabilize democracy in the newly emerging countries, not as a military threat to Russia. Why then would Russia think any differently, regardless of what those in Poland or the Baltics thought? And the argument that Russia could only become strong economically by reforming its economy along the lines of the Washington consensus was widely accepted. These perceptions rationalized away the potential risks inherent in our strategy. One is reminded of the arguments by Federal Reserve head Alan Greenspan in the lead-up to the housing bubble bust that financial innovation would make the system safer and that no financial institutions would take excessive risk that would cause bankruptcy. Just like expectations that housing prices would continue to rise, or could not fall, such stories justify the bubble.

Nor does the argument that NATO expansion was a success — that it helped consolidate democracy, peace, and prosperity in Central Europe — mean that it has not been a bubble. A financial bubble can bring benefits, too — as long as it lasts. The housing bubble, for instance, led to more jobs, new homes, added consumption, and so on. A boom is always a period of good times. The problem with a bubble is not that there are no benefits. It is that the costs of those benefits are ignored even after the bill comes due.

The bill for NATO enlargement is now far overdue. The bigger the bill gets, the nastier the bill collector has to be. The unpleasant bill collector, of course, is Vladimir Putin. And he is not going to go away until we pay the bill. Yet this is a fact that many seem as unwilling to acknowledge today as before. We try to avoid paying the bill, hoping we can exit from the crisis on the cheap. We did this before. The U.S. response to the war in Georgia in 2008 was the so-called reset — an wishful attempt to return to the halcyon days of the Clinton-Yeltsin era. This policy was based on the notion that Russia’s newly aggressive behavior stemmed from the personality of its leader. By banking on Dmitry Medvedev as an alternative to Putin, we continued to maintain the illusion of the missing quadrant and continued to behave accordingly towards Russia.

The response in the Ukraine crisis today is different, but equally inadequate. We have imposed a set of modest economic sanctions against Russia. They are not so strong as to cause real pain in the West, but we pretend they are enough to stop Putin and let us return to business as usual. In fact, as we have shown in an earlier article, the sanctions will not deter Putin from his strategic goal of eliminating what he perceives to be direct security threats to Russia. Indeed, the various “purely-for-show” military measures being discussed by the West — increasing American troop presence and weapons deployment in Eastern Europe and sending NATO trainers to Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, for instance — will likely reaffirm for Putin that his message has gone unheard once again and thus guarantee that he sooner or later makes another, even more shocking, move.

The Bailout

The international political order that has prevailed in Europe for the past two decades cannot continue as before. The bubble has burst. The question for the United States now is, what do we do with all these contingent liabilities we issued to countries on Russia’s doorstep? Regrettably, this metaphorical exercise doesn’t give an easy answer. Quite the opposite: its message is that all answers are costly and messy. It may be useful to look at the range of options. We begin with options at opposite ends of the range.

Option 1: Total bailout = total fulfilment of NATO commitments. A total bailout in the financial crisis would have involved preserving the system at any cost. It would have meant that the U.S. federal government assumed the mortgages of every underwater borrower in America in 2007-08 and bought up all the CDOs and CDO2s that had suffered in value.

The geopolitical analogue today would be for the U.S. to do everything necessary to fulfill all the commitments that NATO expansion implied. We would treat Russia as the Soviet Union, move permanent bases to the new members’ territory, admit Ukraine into NATO, and make it into the forward line of NATO defense against Russia. Militarily, Ukraine would become the West Germany of the New Cold War. Our commitment to Ukraine would include making it economically independent of Russia. Whether we were to do that by developing Ukraine as a sustainable economy integrated into the West, or by maintaining it on permanent subsidies, the costs would be gigantic. (Military experts can estimate the cost on the military side. For the cost of defending Ukraine economically, see our earlier article.)

Option 2: Complete default = complete abandonment of all NATO commitments. In the financial crisis the government would have remained totally passive and allowed the entire system to collapse. In the current situation we would acknowledge that we are not prepared to unconditionally defend countries on Russia’s borders, NATO members or not, and thus we would simply walk away from all these commitments. We would allow Russia to impose any conditions it chooses on the foreign and security policies of all its neighbors, including Ukraine.

It is obvious that both Option 1 and Option 2 are beyond unrealistic and unrealizable. Each in its own way is prohibitively costly. For the total bailout, the cost is monetary. For the complete default, the cost is the unthinkable damage to the international prestige and reputation of the United States and a breakdown of the international order.

A feasible solution will balance the two kinds of costs. That means in practical terms that we will not be able to fulfill all our commitments. We will respect Russia’s perceptions of threats to its interests, but not unconditionally. We will draw some red lines for Russia. Most people will recognize that such compromises are a necessary part of a solution. But a bigger obstacle will be meeting expectations of justice. We had the same issue of who is to blame and who should be punished in the financial crisis. Popular demand then was that a solution must not reward the bankers and excessive risk-takers, who were perceived as the guilty parties. In the current crisis, clearly the popular thing to do in Western eyes is to punish Putin, who has egregiously violated international law by seizing the territory of another country. The irony is that in this crisis the excessive risk takers were the U.S. and NATO, not Putin. One thing is the same: in geopolitics, as in finance, the popular solution is rarely the sensible one. A feasible solution will require that we set aside some norms of fairness for the sake of reaching a just and fair outcome. That is, we should follow the Geithner doctrine.

Option 3: The Geithner doctrine. We have to recognize that in a crisis the proverbial imperative holds: You need to land the plane first. And the “plane” in today’s crisis is Ukraine. We must stabilize Ukraine economically and politically and avoid all-out civil war. To do that, we need Russia’s active co-operation and participation. That will not happen if we insist that our first priority is to punish Putin and isolate Russia. At the same time, just as we could not let the entire financial system collapse, we cannot walk out on current members of NATO. But that forces another unpleasant conclusion: to insist on beefing up NATO first and then expect to get Russia’s support in stabilizing Ukraine — support that is indispensable — is backward.

At every step of the way towards crafting a long-term outcome that is acceptable to both Russia and the West, we will have to heed the Geithner doctrine. We will have to make concessions that many people will regard as unprincipled and distasteful. The sooner we accept this reality, the better. The longer we wait, the more costly the solution becomes, which only increases the incentive to paper over losses. This is a trap we should try to escape.

A proper solution to the crisis must recognize reality and forego the illusion of the missing quadrant. This leads us to ask, how would we have acted differently if we knew then what we know now? That is, that Russia could become strong and bad. Some might say that in that case, we should have just dealt with Russia as the enemy from the outset. We should have dropped any pretense about “winning the peace” and treated Russia as a vanquished foe. Pursuing the conflict to the bitter end, however, would have required military force to remove Soviet nuclear weapons and involved occupation of Russian territory. Nobody would have entertained this option. It is as thoroughly unrealistic an idea as eliminating all forms of debt to avoid future financial bubbles.

Even without perfect foresight, what would a prudent policy have looked like? Policy could not have prevented Russia from becoming strong. If that is so, could we have acted in ways that would have at least prevented this strong Russia from also being “bad”? For instance, would it have helped if we had not gone out of our way to offend Russia before it recovered; if we had not insisted on repayment of Soviet-era debts; if we had offered Russia stabilization funds, as we did for Poland, and more financial aid for restructuring, and so on? Yes, such steps would likely have made Russia more favorably disposed to the United States. But the reality is that we could never have created a Russia that was “good” in our eyes as long as we continued to define “good” and “bad” as we did, namely, whether or not Russia was willing to defer to U.S. policy on all issues, including those the Russians regarded as vital to their own security. A strong Russia will always defend its own interests, and it will insist that Russia, and only Russia, be the one to decide what constitutes a threat to those interests.

Our big problem to this point has been our proclivity to substitute our reading of the threats to Russians’ national security for theirs, and when they do not accept our reading, we label them as “bad.” This is why NATO expansion mattered. We presumed NATO expansion could be no threat to Russia because we knew that we were not a threat to Russia. We presumed that Russia would perceive NATO expansion as we did, not as the Poles or the Baltic States did. Russia, however, viewed NATO expansion exactly as the Poles did, as a bulwark against them. Given the fundamentally conflicting perceptions over NATO expansion, a prudent policy would have used EU expansion to obtain the benefits for the new democratic states, without causing the Russians to feel threatened.

We are long past the point where we can argue that NATO expansion is no threat to Russia. Nonetheless, we must honor our commitments to the current members. That will be a huge burden to us, but it is ours to pay. Going forward, the one thing we cannot do is repeat the mistakes of the past, that is, issue unconditional, unlimited commitments to new members. Ukraine’s security can only be guaranteed by the cooperation of the West and Russia. Accomplishing this will be difficult, but necessary. In geopolitics, as in the world of finance, the solution to a crisis so deep and so long in the making cannot be easy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Ukraine, NATO Enlargement, and the Geithner Doctrine

June 10, 2014