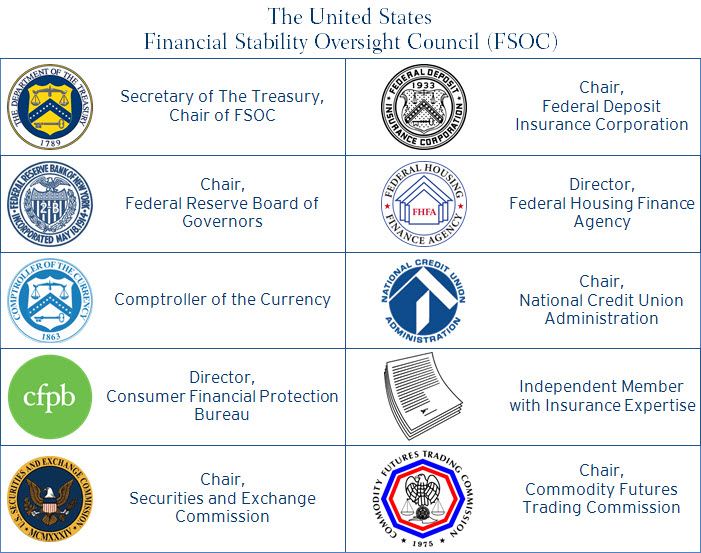

The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), created by the Dodd-Frank Act, should be retooled to enhance its ability to maintain financial stability and minimize the risk of another financial crisis, says Donald Kohn, a senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution and its Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy.

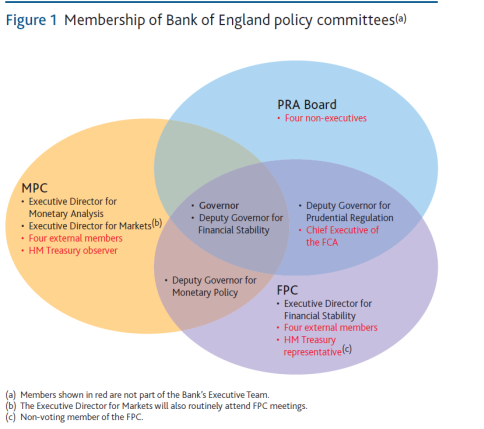

“We’ve renovated our regulatory and supervisory structures in charge of making the financial system more resilient,” Mr. Kohn said. “We’ve made progress, but my view is that the job isn’t done yet.” Mr. Kohn is a member of the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee and a former vice chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board.

This diagram was originally published in the Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin of 2013 Q3

In remarks delivered at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, Mr. Kohn cited several shortcomings of the structure of the 10-member FSOC, currently chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury:

- It’s composed of several independent regulators, several of which have mandates to focus only on specific institutions or markets, not on the stability of the overall financial system.

- There are gaps in regulation among FSOC and its member agencies that could interfere with the ability to reduce systemic risk

- Data is not widely shared among the constituent agencies to the extent that it should be.

- FSOC is likely to face big obstacles to implementing countercyclical macroprudential policies, that is, policies designed to make credit less plentiful in booms and more plentiful in busts.

- FSOC has very limited tools [..] and recommendations to other agencies might take considerable time to be implemented.”

Accepting that Congress is highly unlikely to change the current fragmented structure of U.S. financial regulation, Mr. Kohn made six suggestions for changing FSOC:

- Give each of the agencies with seats on the FSOC a clear objective to maintain financial stability, which would make it harder for an agency to reject or tone down a recommendation that FSOC deemed important to reduce systemic risk.

- Require FSOC agencies to share data in response to requests from one another.

- Require FSOC to include in its annual report to Congress an assessment of the regulatory perimeter, i.e. where risks are developed outside the most heavily regulated sectors, and whether laws need to be altered as a result.

- To give FSOC the independence to act to implement unpopular counter-cyclical policies, give it a new, independent, presidentially appointed, Senate confirmed chair, making the Treasury secretary a member but not the chair of the committee, and give FSOC its own source of funding and staff, perhaps by folding the Treasury’s new Office of Financial Research into the FSOC.

- Require the FSOC to consider the costs and benefits of its actions and recommendations.

- Give the more independent FSOC tools it can use more expeditiously to address potential systemic risks, such as giving it more say over triggering countercyclical capital buffers for financial institutions, as outlined in the Basel III international capital accord.

“These changes would require legislation and that’s not going to happen any time soon in our contentious political environment,” he said. “But it can’t hurt to start a conversation that might bear fruit at some future date.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Tweaking the Financial Stability Oversight Council to Reduce Risks of Another Financial Crisis

April 17, 2014