Nobody predicted that the desperate act of a young Tunisian who set himself on fire in protest of government policies that left him jobless and disenfranchised would ignite protests for democratic and economic reforms across the Middle East. Since this incident, Tunisia’s government has fallen and demonstrations have spread to Yemen, Jordan, Algeria, Sudan and Egypt, where only yesterday well over a million people took to the streets to demand the ousting of President Mubarak, whose days appear numbered. Yemen’s president has also announced that he will not seek re-election or hand power to his son, while the prime minister and government of Jordan was dismissed by the King after demonstrations. The world has been watching and Middle East experts, politicians and pundits have weighed in on the unfolding events. Many wonder whether we could have foreseen this wave of unrest.

On the contrary, until a few days ago many pundits were still predicting that instability – let alone regime change – would not spread to Egypt. Some highlighted the apathy, cynicism, fatalism and fear of Egyptian citizens in predicting the persistence of the longstanding status quo in Egypt. “No Sign Egypt will take the Tunisian Road” was the title of a BBC article from Cairo just two weeks ago. It noted that “no one could describe Egyptian society as ‘aspirational’… Egyptians do not see any way that they can change their country or their lives through political action, be it voting, activism or going out on the streets to demonstrate.”

Other major media outlets predicted that the status quo would continue in Egypt, citing limited freedoms as a distinguishing feature of Egypt. A recent Foreign Policy article suggested that Egyptian President Mubarak differed from the exiting Tunisian ruler because Mubarak cleverly combined limited freedoms with co-option and some opportunities for Egyptians to express their political grievances. The Economist argued that Egypt’s “relatively free press not only gives healthy air to protest, but acts as the sort of early-warning system that [Tunisia’s] Ben Ali, due to his own repressive tactics, sorely lacked.”

Time magazine predicted that no “domino effect” would result from Tunisia’s revolution, and that the U.S. would proactively prevent Egypt from following Tunisia’s path, while the Economist and BBC contrasted the weakness of Tunisia’s security forces with the superior training and equipment (largely provided by the U.S.) of Egypt’s. And a few days ago another expert explained in Foreign Policy why, in contrast with Tunisia, the Egyptian army would not side with the public, only to have the military announce days later that they respected the people’s legitimate demands.

To be fair, it is easy to criticize after the fact. However, most pundits focused on the differences between Middle Eastern countries to underscore the low probability of Tunisia’s revolution spreading throughout the Arab world. Consequently, not enough attention was paid to the fact that important similarities – notably perennial rulers, absence of freedoms, corruption and a disenfranchised youth, all of which fueled people’s discontent – would far outweigh some perceived differences across countries.

Democratic Accountability

The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), which has been compiled since the mid-1990s, measure six components of governance. One very important component is Voice and Democratic Accountability (V&A) [1]. The V&A indicator measures not only whether countries hold elections, but also whether these are truly contested, legitimate, free and fair, whether the government is accountable to its citizens, and whether there are basic freedoms of expression and association, including protection of media freedoms, of civil society, and against human rights abuses.

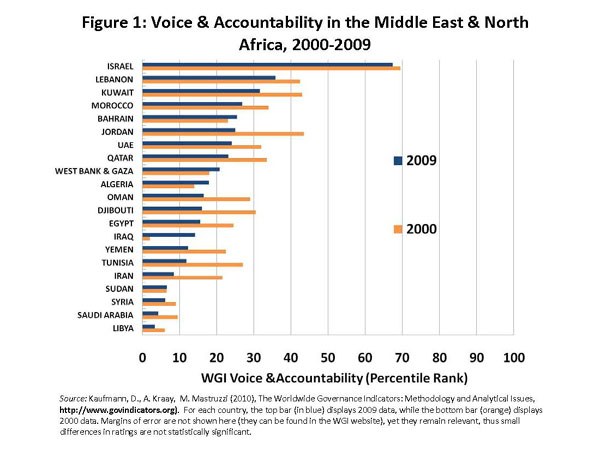

The sobering reality is that in terms of Voice and Democratic Accountability, the Middle East has rated very poorly relative to the rest of the world for many years. With very few exceptions, there is little variation on this indicator across the region. Worse, even though the region began the past decade underperforming on V&A, most every country in the region has deteriorated since and ended the decade at even lower levels of V&A.

Figure 1 shows the extent to which the Middle East has been afflicted by a severe deficit in accountability. In fact, all Middle East countries, with the exception of Israel, rank in the bottom half of the world on V&A. Within the Arab world, Lebanon and Kuwait are above the rest, but still remain in the bottom third globally. The remaining Middle East countries perform even worse and are in the bottom quartile (25th percentile or below) in the V&A component, including Tunisia and Egypt (both underperformed rather similarly). Countries like Iran, (North) Sudan, Syria, Saudi Arabia and Libya rank among the very bottom (10th percentile or below). From a broader global perspective, Egypt’s percentile rank at 15.6 in 2009 (meaning that over 170 countries around the world rated above Egypt) compares extremely poorly with countries like South Africa (67th percentile), Brazil (62), Ghana (61) and Indonesia (49). By the end of the decade, Egypt rated similarly in V&A to countries like Cote d’Ivoire, Angola and Congo.

Figure 1 also illustrates the deteriorating pattern in V&A over the past decade for many Middle Eastern countries in contrast to other regions. It is noteworthy again that there was a sharp deterioration in V&A in Tunisia, while Egypt experienced a similar, though not as large, decline during this period. The data are admittedly of an aggregate nature and provide a broad benchmark for the performance of the Middle East. However, in light of the recent emphasis on the very particular differences across countries in the Middle East region, it is noteworthy that the data point to an important similarity across the Arab world — namely that basic freedoms have been absent and deteriorating.

In fact, all the bottom eight Middle East countries in 2009 experienced deteriorations in V&A from 2000 with the exception of Iraq, which started from the very bottom. It would be naïve to suggest that all these countries are now equally vulnerable to major unrest or regime change or to insinuate that those countries rating immediately above this list (whose performance is also subpar) are not vulnerable. There are multiple, complex and unpredictable determinants of unrest and regime change. But, starting with a hard-nosed look at the democratic deficit does help.

Youth Disenfranchisement and Their Resourcefulness

The disenfranchisement that has plagued Middle East youth is also quite evident in the data. On average, young people account for about 30 percent of the Middle East population, compared with less than 20 percent in the developed world. In addition, youth in the Middle East tend to be economically and politically disenfranchised. Even prior to the recent recession, youth unemployment rates in the Middle East and North Africa stood at an estimated 25 percent or twice the unemployment rate of the rest of the world. For some countries, including Egypt, the youth unemployment rate approached 30 percent or about six times its adult unemployment rate. Most of the youth live on less than $ 2 a day.

The socio-economic frustrations of the youth in the Middle East are only compounded by their inability to freely express themselves and demand change through democratic channels. They are witness to unfree and tainted elections, repression of the media and civil society and government corruption. In addition, there are few mechanisms in place to hold governments accountable for their political and economic decisions. Where normal channels are unavailable, they resort to untraditional methods for venting their frustrations. In particular, they have resourcefully used social media (and gotten around government censorship) to connect, organize themselves and mobilize protest movements.

Accountability in Donor Aid by the Rich Countries

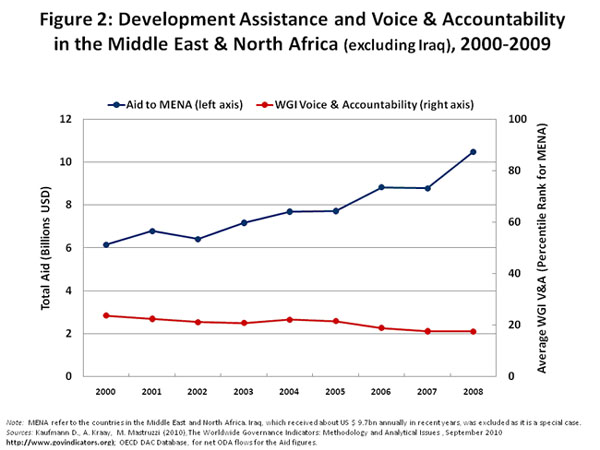

The recent events have made it evident to Western powers that citizens of Arab countries are determined to shape their own destiny. But, the unfolding situation in the region warrants a re-examination of the West’s historical support for autocratic regimes. Let us look specifically at how donors have responded to the democratic deficit in the Middle East over the past decade. On aggregate, as Figure 2 indicates, donors have been oblivious to poor democratic governance in the region. In fact, while Voice and Accountability have deteriorated over the past decade, aid increased significantly, even when excluding the ‘special case’ of Iraq from this sample (from US $6.2 billion to $10.5 billion). In fact, almost all of donor development aid is channeled to Middle East countries that have low democratic accountability by the standards of other developing countries.

Some may defend such aid allocations by resorting to the realpolitik argument that aid, including “development aid”, is given to Middle East countries not only to raise living standards, but also to achieve political and security objectives with non-democratic allies. The first problem with this practice is that governance deficits tend to undermine development and job creation for the low income and youth strata of the population, and thus breed discontent. The second problem is that nowadays citizen-led revolutions against non-democratic regimes can unpredictably be sparked almost anywhere. Once the spark is ignited, they dwarf any possible “propping up” effect that foreign aid may have in perpetuating these regimes during seemingly stable times.

The events in the Middle East are a rude reminder that it is high time to revamp donor aid strategies so to concretely elevate the priority of democratic governance in development assistance. They are also a wake up call for analysts (us included) to revisit how ‘political stability’ and country risk is assessed and measured in undemocratic regimes, and it is a reminder that uncertainty and unpredictability needs to be taken seriously. Against the background of the newly found power of the people and social media, the dramatic events that are unfolding are also a rude reminder that in the global race to write instant analysis as events begin to unfold, a rush to make predictions is risky especially when little attention is paid to the comparative data at hand.

[1] The other governance indicators are: Political Stability/No Violence, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law and Control of Corruption. The data for each component, as well as the underlying data can be found here (link). It is noteworthy to also point out that countries like Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen, Sudan, Syria and Iran, among others, experienced declines in the Political Stability indicator over the past decade.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edTunisia, Egypt and Beyond: Fewer Predictions, More Data and Aid Reform Needed

February 2, 2011