In the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic, foreign capital flows to China were extremely strong over a period of many years. This held for foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio, and other investment flows and looks to be reversing in the years since the pandemic. Portfolio and other investment flows to China look especially weak, while they are at the stronger end of the historical range for the rest of emerging markets (EM).

The interesting question is why this decoupling is happening, something that is obviously hard to infer from flows. This post looks separately at FDI, portfolio, and other investment flows around key events such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the start of President Donald Trump’s second term. The fall in FDI flows to China is part of a longer-running trend that has been ongoing for many years. The drop in portfolio flows to China is related to the start of Trump’s second term, while the fall in other investment flows to China seems to line up with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It goes without saying that none of this is conclusive and is something we will return to in a future post.

Decoupling of global capital flows

We compile data on nonresident foreign direct investment, portfolio, and other investment flows from the balance of payments for 25 of the world’s biggest emerging markets. We make a number of adjustments to give a more accurate representation of flows over time. The most important of these is that we net out reinvested earnings from FDI, which in balance of payments accounting get booked as an inflow when no actual flow takes place. The FDI flows we show here are therefore “true” flows and can be thought of as approximating genuine new FDI going into a country. Portfolio flows are flows into stocks and bonds across EMs, while net other investment consists of bank intermediated flows that include trade finance, loans, and many other things.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

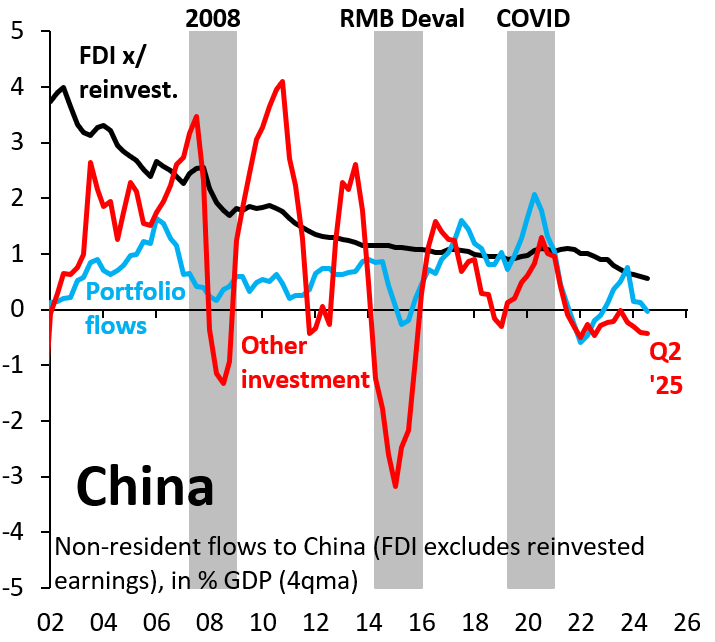

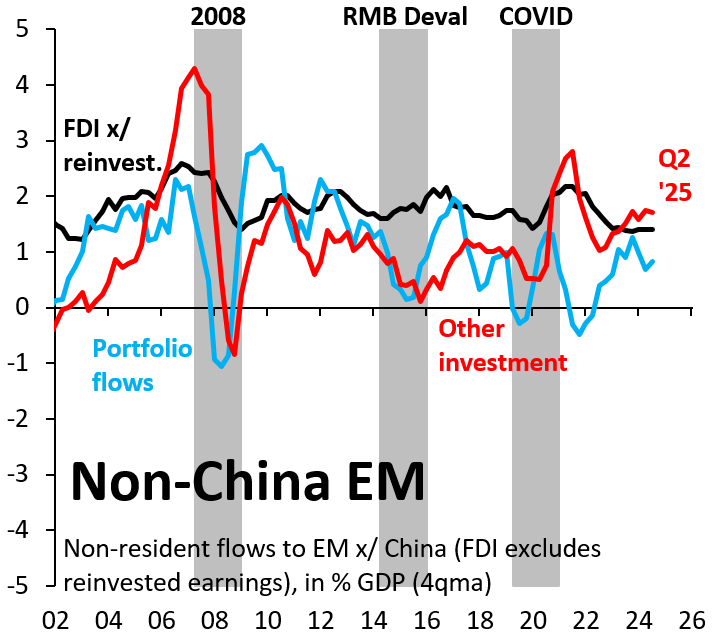

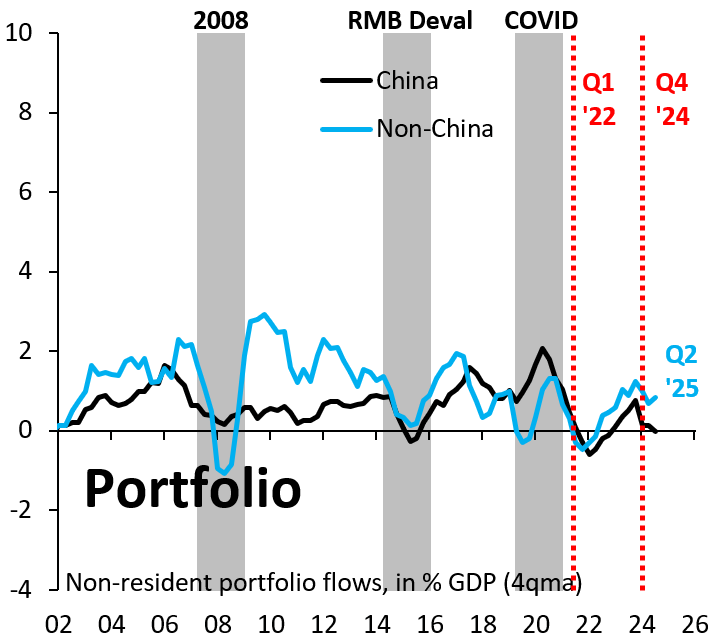

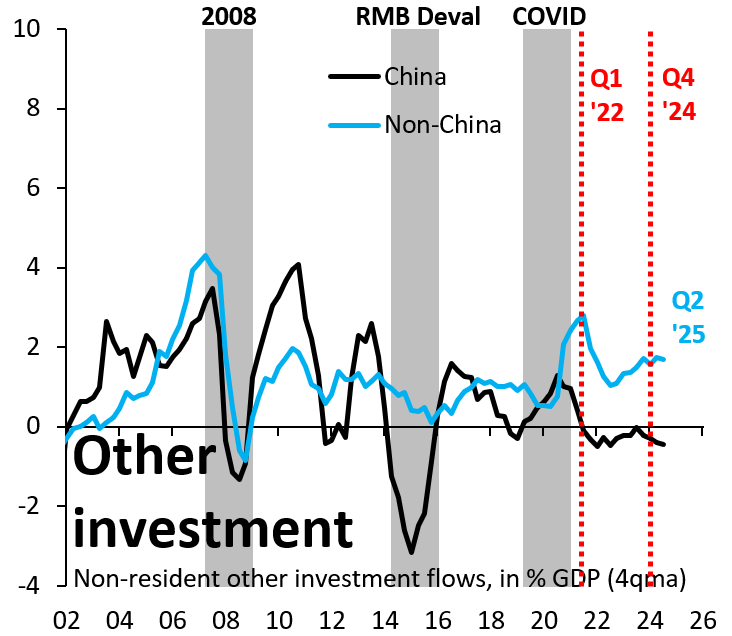

Figure 1 above looks at what these flows look like for China, where we show each category as a four-quarter moving average scaled by nominal GDP in U.S. dollars. FDI excluding reinvested earnings is the black line, portfolio flows are the blue line, and other investment flows are the red line. Positive readings mean inflows into China by nonresident investors. Negative readings mean outflows. Figure 2 is the same exact thing across the 24 other EMs in our database. We shade three episodes in gray that are historically important for capital flows to EM: (i) the global financial crisis in 2008; (ii) the renminbi devaluation episode in 2014/5, which caused substantial capital flight from China; and (iii) the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. What is clear from these figures is that capital flows to China are decoupling from the rest of EM. This is most noticeable for portfolio and other investment flows, which are more reactive at high frequency, but it looks like there is some decoupling in FDI as well.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

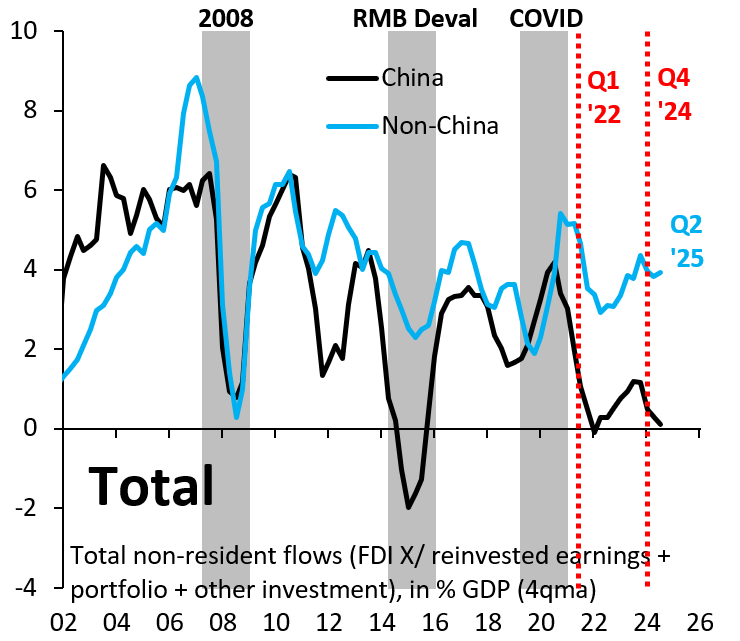

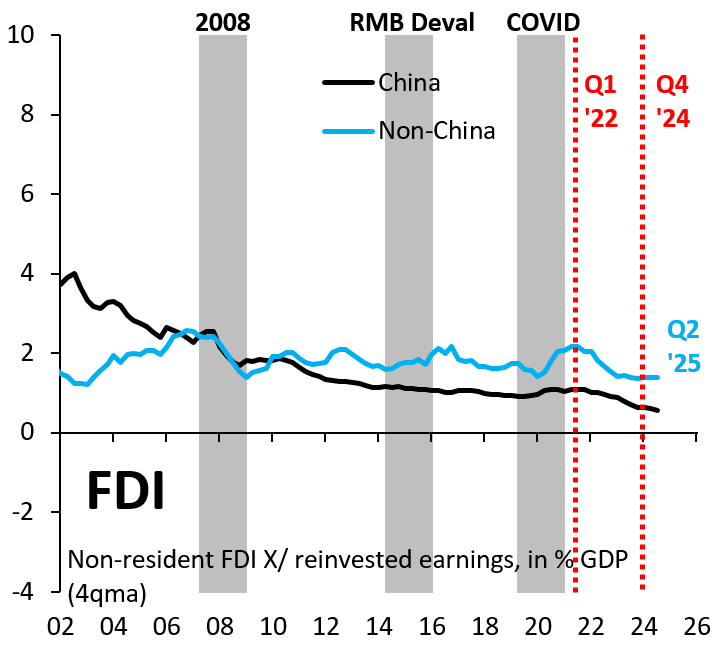

It is impossible to tell what exactly drives this decoupling, but Figures 3 through 6 provide some perspective. Each chart compares flows to China with the rest of EM and lines them up against key geopolitical and other events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the start of Trump’s second term. Figure 3 looks at the sum of FDI, portfolio, and other investment flows. In aggregate across all three categories, the decoupling is striking and looks like it came in the immediate wake of COVID-19. Figure 4 looks at FDI flows only. A decoupling is noticeable here also but does not line up with any single event. Instead, it looks like the fall in FDI flows to China is part of a longer-running trend that has seen flows to China decouple from other EMs.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

Figures 5 and 6 look at portfolio and other investment flows, respectively. It looks like portfolio flows to China decoupled from the rest of EM recently, potentially coinciding with the start of Trump’s second term. Other investment flows decoupled very markedly after COVID-19 and perhaps as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Overall, there are likely to be multiple catalysts for divergent flows to China, and it is difficult to do a precise attribution. However, overall it looks like flows to China are substantially weaker than to the rest of EM.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Trends in global capital flows to emerging markets

November 7, 2025