The economic picture in the eurozone is growing increasingly challenging. High frequency indicators point to mounting weakness in Germany, France, and many other countries. As the budget standoff in France highlights, fiscal space is extremely limited. Given this, there are mounting calls for joint EU debt issuance, but this remains a political impossibility on any meaningful scale. The European Central Bank (ECB) has cut its policy rates by the same amount as the Fed so far in 2024. There is now scope for monetary policy to decouple more forcefully from the Fed, with more aggressive rate cuts helping bring a sorely needed fall in the single currency.

Mounting European weakness

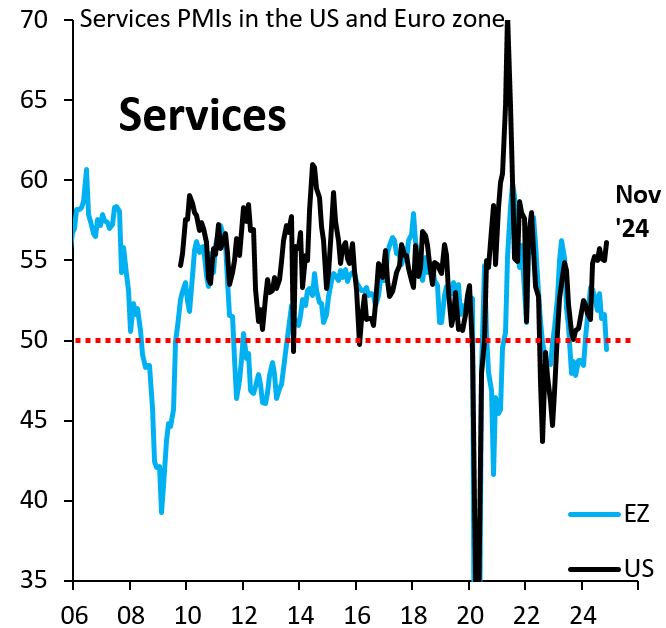

High-frequency indicators point to mounting economic weakness in Europe. Figures 1 and 2 show manufacturing and services PMIs (purchasing manager indices), respectively, for the United States (black) and eurozone (blue). These are balance of opinion surveys, where readings above 50 signal expansion and readings below signal contraction. These surveys capture sentiment that tends to be more volatile than hard data like GDP or industrial production, but there is nonetheless a high correlation between the PMIs and activity.

The U.S. and eurozone PMI series tend to move closely together, but there are exceptions, the most obvious of which is the Euro periphery debt crisis in 2011/12, when sentiment in manufacturing and services in the eurozone fell substantially below that in the U.S. A similarly large gap is opening up now, with sentiment in the eurozone again falling sharply relative to the U.S.

Figure 1. Manufacturing PMIs in the US and eurozone

Figure 2. Services PMIs in the US and eurozone

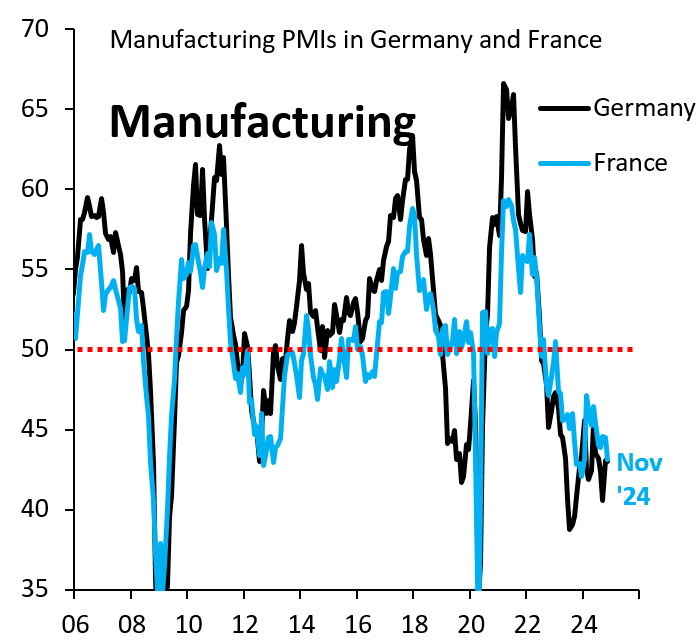

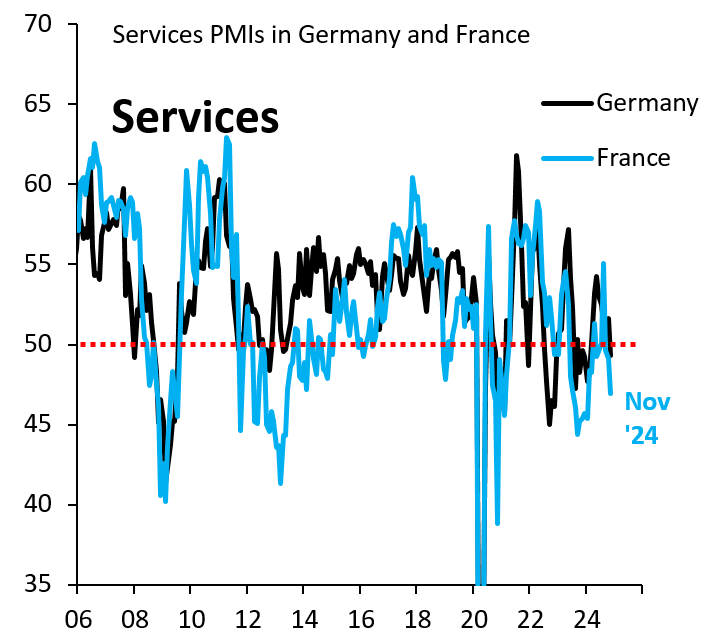

Much attention is being devoted to Germany as the “sick man of Europe,” but recent weakness is more broad-based than that. Figures 3 and 4 show manufacturing and services PMIs, respectively, for Germany and France. Manufacturing sentiment is unambiguously weak in both places, while services sentiment has deteriorated more sharply in France. Given that France and Germany are the two biggest eurozone economies, it is inevitable that this weakness will radiate out to other countries in the single currency.

Figure 3. Manufacturing PMIs in Germany and France

Figure 4. Services PMIs in Germany and France

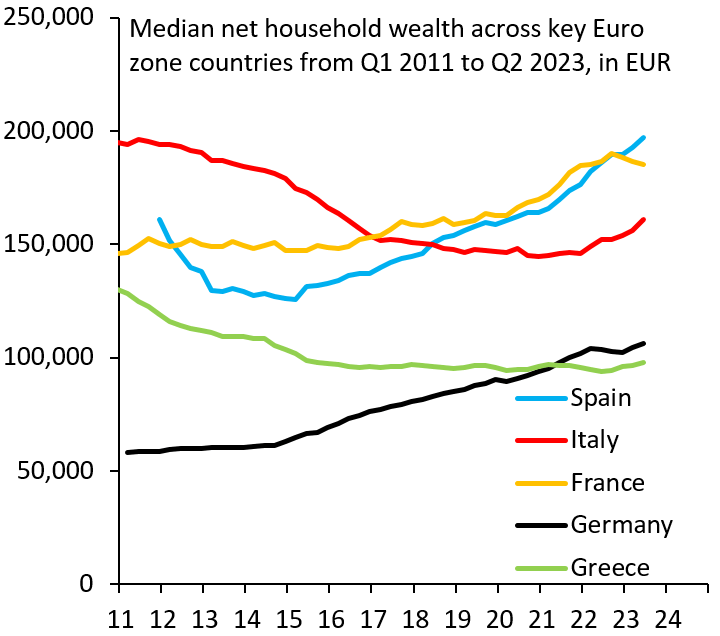

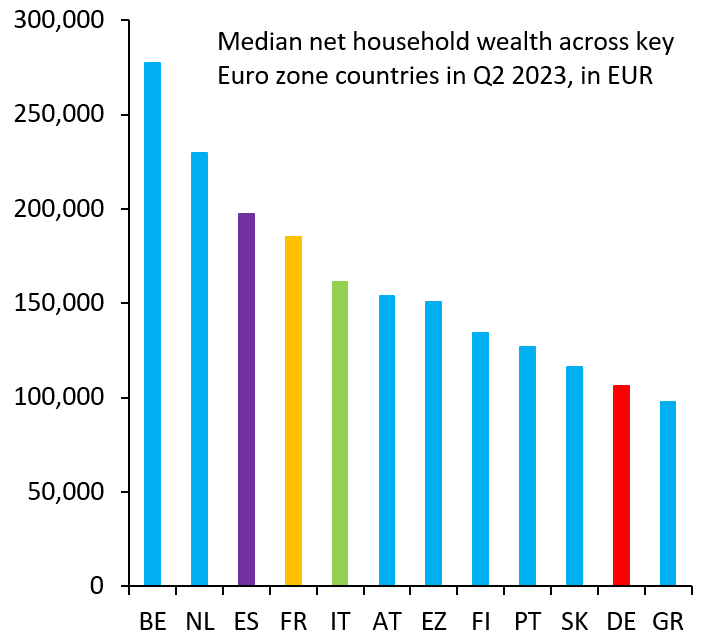

The budget standoff in France is a reminder how constrained fiscal space is in much of the eurozone. Not surprisingly, this is giving rise to mounting calls for joint EU debt issuance, with the purpose of shifting some or all funding for defense and climate change off national budgets. Unfortunately, barring a major crisis, any meaningful joint debt issuance is a political impossibility, because of concerns in low-debt countries like Germany that this could further distort incentives away from needed debt reduction. New ECB data on net household wealth, which is mostly housing but also includes financial holdings, helps put this in perspective. Median net household wealth in France, Italy, and Spain is substantially above that in Germany, which is on par with Greece (Figure 5). Given this, the argument for joint issuance is weak, as countries with high public debt levels have the means to help themselves (Figure 6). This does not rule out joint debt issuance categorically, but means it will remain the exception, as in the case of one-time joint issuance during the pandemic.

Figure 5. Median net household wealth across key eurozone countries from Q1 2011 to Q2 2023, in euros

Figure 6. Median net household wealth across key eurozone countries in Q2 2023, in euros

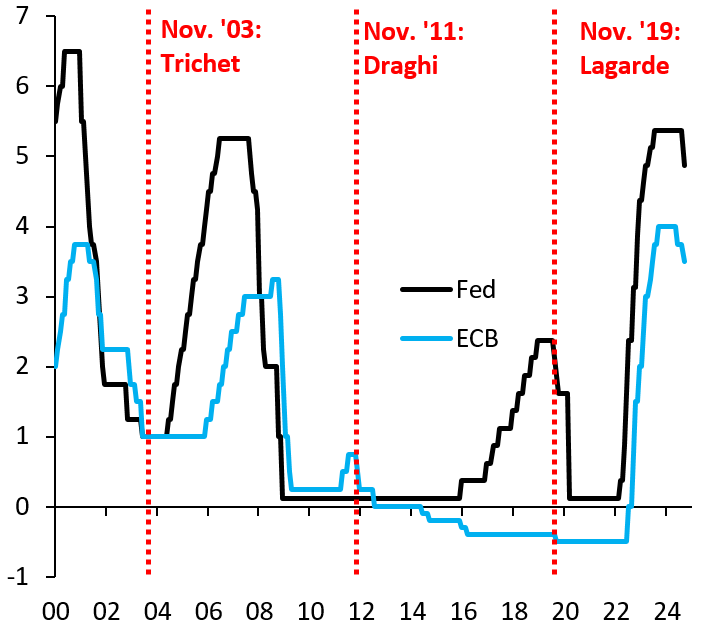

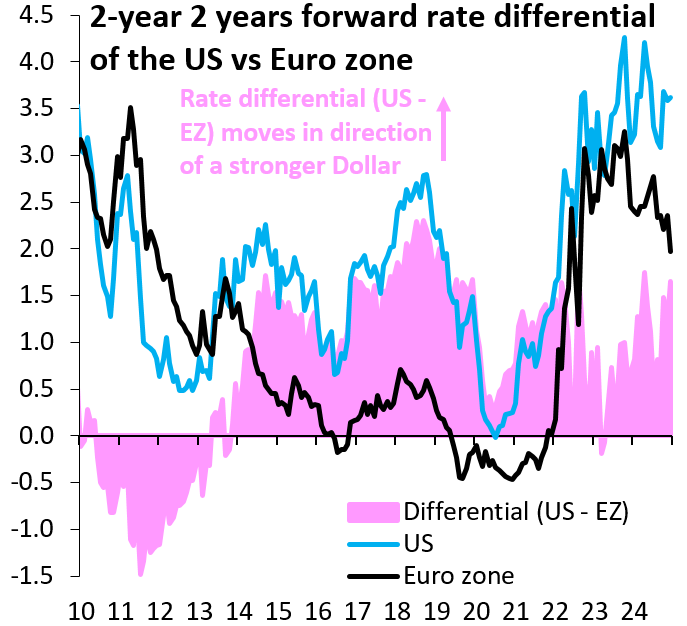

With fiscal policy constrained, monetary policy is once again the only lever that can provide cyclical support. The ECB closely followed the Fed in its 2022 hiking cycle and has been cutting alongside the Fed this year (Figure 7), but there is now room to decouple forcefully. Admittedly, inflation has fallen more slowly than hoped this year, but—on a forward-looking basis—downside risk to the ECB forecast is building. The period from 2012 to 2014 provides a template for more proactive easing. At the time, Mario Draghi was ECB president and was able to move the U.S.—eurozone rate differential against the euro (Figure 8) by around 300 basis points, as markets priced the shift to negative interest rates and quantitative easing. Differentials are once again shifting against the euro, but current moves are small compared to 2012-2014. There is need for greater urgency from the ECB, with more aggressive rate cuts bringing a sorely needed weaker euro as a means of cyclical support.

Figure 7. Fed and European Central Bank policy rates

Figure 8. 2-year 2 years forward rate differential of the US vs. eurozone

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Time for the European Central Bank to decouple

December 5, 2024