Until recently, climate diplomacy has been fraught with danger for U.S. presidents. Caught between naysayers at home and close allies who pressed the United States for action, the three presidents who preceded Barack Obama struggled to reconcile domestic and international pressures but failed to find a winning formula. Despite periods of constructive engagement, the U.S. was a chronic spoiler, unable to commit to emission reduction goals necessary for effective global action. The absence of the US—the world’s largest historic emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and wealthiest nation—was the Achilles’ heel of global climate negotiations, creating a diplomatic stalemate and blocking global progress.

President Obama has changed this unhappy narrative and brought a new face to U.S. climate diplomacy. As world leaders assemble for the Conference of the Parties (COP) in Paris next month, the U.S. has been at the center of the negotiations, cajoling reluctant countries to adopt more ambitious goals, shaping the architecture of a new agreement and trumpeting its own ambitious commitments as an example of climate responsibility.

Men work at the U.S. Pavilion on the site where the upcoming COP21 World Climate Summit will be held at Le Bourget, near Paris, France (REUTERS/Benoit Tessier)

How did the U.S. become a strong advocate for global action after two decades of failed leadership? Three factors have converged to create a new dynamic that a motivated president has been able to exploit.

First, growing alignment between the U.S. and China has undercut the long-standing narrative that developing countries would take advantage of U.S. emission reductions by sitting on their hands while the costs of emission control made U.S. industry uncompetitive.

Second, for the first time since the industrial revolution, U.S. emissions are on a downward trajectory as a result of market forces and government policies, enabling the U.S. both to take credit for progress and to commit to further reductions that would have seemed unrealistic just a decade ago.

Finally, the Kyoto model of top-down targets and timetables has been replaced by a new international framework that calls for countries to put forward reciprocal but unilateral commitments that are not binding under international law. Not only has this created a more fluid negotiating environment but it has laid the groundwork for an agreement that likely does not require Senate ratification, avoiding the collision between the Executive Branch and Congress that doomed the Kyoto Protocol.

President Obama has changed this unhappy narrative and brought a new face to U.S. climate diplomacy.

Economic fears and U.S. climate policy under President George H.W. Bush

Before the Obama administration, U.S. presidents feared that any serious effort to reduce GHG emissions would undermine economic growth. This fear was fueled by the seemingly inexorable rise of emissions as GDP increased, suggesting that emissions could only be reduced by shrinking economic output. Deep economic insecurity further magnified the fear as U.S. dominance was challenged first by Japan in the 1980s and then by China, Korea, and other emerging economies in the 1990s.

Buildings are pictured on a hazy day in Beijing (REUTERS/Jason Lee)

George H.W. Bush, struggling for re-election in a difficult economy, reflected these anxieties in his stunning refusal to agree to targets and timetables to reduce emissions at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, a position that brought him condemnation from U.S. allies and nearly resulted in the resignation of his EPA administrator William Reilly.

With targets and timetables removed, the U.S. acceded to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) negotiated in Rio but a deep division remained between the U.S. and its European allies over whether to freeze emissions at or below 1990 levels, a goal that President Bush initially supported but rejected at Rio as unachievable.

U.S. acceptance of the UNFCC also papered over a simmering dispute over the treatment of developed (or Annex I) and developing countries. Despite U.S. misgivings, the convention assigned advanced economies primary responsibility for climate mitigation based on their historical contribution to emissions and greater financial resources. It also committed the developed world to assist poorer nations in coping with climate change.

Before the Obama administration, U.S. presidents feared that any serious effort to reduce GHG emissions would undermine economic growth.

The Kyoto Protocol debacle

This basic architecture shaped the negotiating process that culminated in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, under which Annex I countries made binding commitments to reduce emissions below 1990 levels (the goal that the European Union had unsuccessfully pursued at Rio). Consistent with the UNFCC, no obligations were placed on developing countries.

The Clinton administration played a complex role as the Kyoto Protocol took shape in the mid-1990s. Embracing the goal of freezing emissions at 1990 levels that his predecessor had resisted, the president put forward a seemingly ambitious Climate Action Plan. But the plan was voluntary and implementation was anemic. In the absence of effective policies, a booming economy caused U.S. emissions to climb by 12 percent between 1992 and 2000, putting the Kyoto targets effectively out of reach.

A Legambiente activist demonstrate during a protest to celebrate the anniversary of the Kyoto protocol environmental treaty in downtown Rome (REUTERS/Max Rossi)

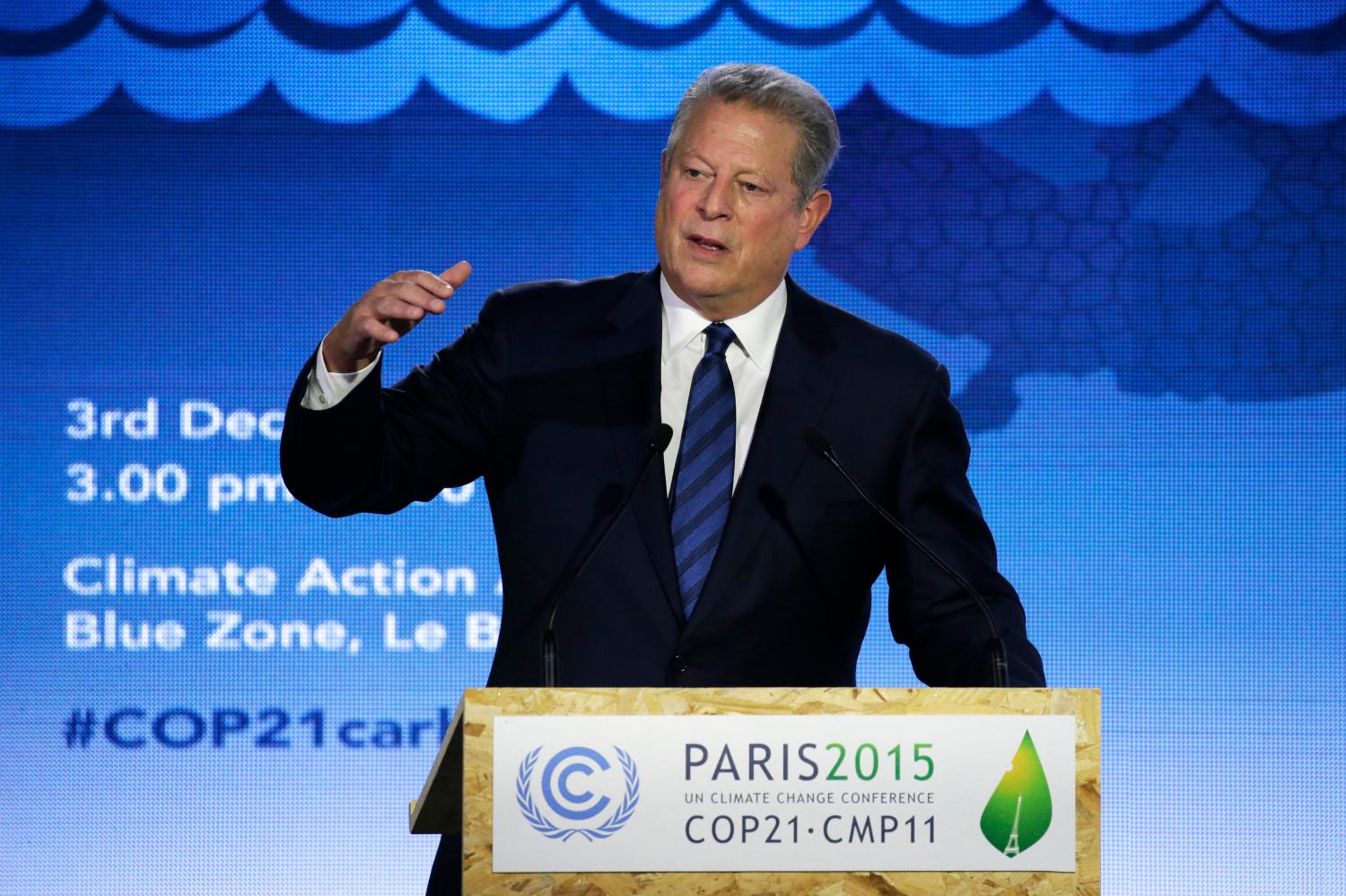

The U.S. was a constructive negotiating partner before and during the Kyoto COP, with Vice President Al Gore making a dramatic eleventh-hour appearance to push the draft Protocol across the finish line. But facing deep bipartisan opposition, President Clinton made no effort to seek Senate ratification. The death knell for the protocol was the Senate’s 95-0 passage of the Byrd-Hagel resolution condemning it on two related grounds: first, the risk of “serious harm to the United States economy, including significant job loss, trade disadvantages [and] increased energy and consumer costs”; and second, the failure to “mandate new specific scheduled commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for Developing Country Parties” on a parallel track with the emission reductions required of developed countries.

The George W. Bush administration embraced these themes, denouncing Kyoto in 2001 as “an unfair and ineffective means of addressing global climate change.” Disengaging from the international process as a threat to U.S. economic interests, the administration embarked on a new path, emphasizing improving U.S. carbon intensity rather than absolute emission reductions and technology development rather than regulation. This approach further alienated America’s European allies and failed to command public support, ultimately leading to renewed bi-partisan interest in climate legislation.

In the absence of effective policies, a booming economy caused U.S. emissions to climb by 12 percent between 1992 and 2000, putting the Kyoto targets effectively out of reach.

Finding victory in defeat at Copenhagen

Barack Obama’s election in 2008 revived hope for U.S. participation in a new international agreement that would replace the Kyoto Protocol. But the disappointing Copenhagen COP in 2009 revealed that, even with a more cooperative U.S., the Kyoto model of top-down binding emission targets was deeply flawed and that the longstanding gulf between developed and undeveloped countries had to be narrowed to assure the U.S. public that our major economic rivals were assuming burdens proportional to our own.

Copenhagen did not result in the comprehensive treaty many had desired but, with the help of President Obama, a small group of major emitters entered into a last-minute political agreement that contained the seeds of future progress. This “Copenhagen Accord” was negotiated by both developed and developing countries, including China and India. Underscoring that climate change is “one of the greatest challenges of our times,” the accord affirms the goal of preventing temperature increases above 2° Celsius. It then calls upon Annex I (developed) countries to commit to and implement “quantified economy-wide emissions targets” for 2020 and upon developing countries to identify and carry out “nationally appropriate mitigation actions” within the same time-frame.

U.S. President Barack Obama addresses the session of United Nations Climate Change Conference 2009 in Copenhagen (REUTERS/Bob Strong)

The accord did not specify targets for Annex I countries or mitigating actions for developing countries but allowed individual nations to set goals unilaterally through a bottoms-up process. Strongly criticized at the time as a retreat from the Kyoto model of jointly determined targets and timetables, this approach substituted a system of political accountability for one of legally binding obligations and encouraged countries to base commitments on their individual capabilities and values, informed by climate science and the scrutiny of the world community. Ultimately, the accord was signed by dozens of countries who submitted 2020 action plans—a process now being repeated as the Paris COP approaches.

The accord also took important strides toward narrowing the divisions between Annex I nations and developing economies by underscoring a set of shared goals and commitments to progress. Unlike under the Kyoto Protocol, emerging economies assumed responsibility for mitigation, albeit at a pace that recognized their lower standards of living and higher aspirations for growth.

Copenhagen did not result in the comprehensive treaty many had desired but, with the help of President Obama, a small group of major emitters entered into a last-minute political agreement that contained the seeds of future progress.

Declining U.S. emissions

In the aftermath of Copenhagen, the Obama administration committed to reducing U.S. emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020—a significant break with the long-standing U.S. refusal to agree to concrete reduction targets. The commitment itself mirrored the goals and timetables in the then-pending Waxman-Markey legislation, which supporters hoped would provide the legal tools to lower U.S. emissions. But Waxman-Markey failed to advance in the Senate amid concerns about the economy. In the wake of its demise, the path to meet the president’s goal seemed to evaporate.

Surprisingly, however, U.S. emissions started to decline anyway and by 2012 were 11 percent below 2005 levels. One unanticipated cause of this decline was the boom in U.S. natural gas production as hydraulic fracturing (a.k.a. “fracking”) was used successfully to extract gas from shale formations. As supplies rose rapidly, prices plummeted and natural gas became highly competitive as a power plant fuel, replacing higher emitting coal and significantly lowering the carbon footprint of the power sector.

Denver, which once had some of the most polluted air in the United States, has cleaned up its act to become the first major metropolitan area to fully comply with federal air quality standards, officials announced on August 9, 2002 (REUTERS/Robb Williamson)

Administration policies added to the momentum toward lower emissions. As the legislative window closed, the administration shifted its emphasis to implementation of the Clean Air Act, whose application to GHG emissions had been upheld by the Supreme Court in its 2007 Massachusetts v. EPA decision. Using this authority, the EPA mandated deep reductions in tailpipe emissions and improvements in fuel economy by passenger cars and light trucks. More recently, the EPA issued its massive Clean Power Plan (CPP) targeting a 32 percent reduction in power plant emissions below 2005 levels by 2030.

As the Paris COP approached, the downward trajectory of U.S. emissions combined with the effective use of existing authorities enabled the Obama administration to project confidence that additional reductions are within reach. On November 9, 2014, as part of a historic U.S.-China agreement on climate change, president Obama announced a goal of reducing U.S. emissions by 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. This stretch goal, later included in the U.S. Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) for the Paris COP, has provided a powerful talking point to challenge other countries to raise their level of ambition.

In the November 2014 joint agreement, Chinese President Xi Jinping simultaneously committed to peaking GHG emissions by no later than 2030 and increasing non-fossil energy to 20 percent of total power production in the same timeframe. This demonstration of solidarity by the world’s two largest emitters was further evidence of convergence between developed and developing economies and a powerful driving force for a successful outcome in Paris.

In the aftermath of Copenhagen, the Obama administration committed to reducing U.S. emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020—a significant break with the long-standing U.S. refusal to agree to concrete reduction targets.

Is the climate diplomacy glass half full or half empty?

By shrewdly leveraging declining U.S. emissions, finding common ground with China, and advocating a system of reciprocal but non-binding national commitments, President Obama has played his cards well. His critics on the right are as vocal as ever but, if the agreement reached in Paris does not impose obligations under international law; they will likely be powerless to block it in Congress. And with nearly all large emitters submitting INDCs, the stage is now set for a positive outcome at the COP on terms largely set by the U.S.

Looking ahead to Paris and beyond, however, there are several sobering concerns. For one thing, India is reluctant to join China in committing to peak emissions by a certain date. India’s high dependence on coal and skyrocketing demand for electricity could result in surging emissions that dwarf those of China. In a similar vein, even with the substantial emission cuts pledged by the U.S. and the European Union, global emissions will continue to climb and will be dangerously out of alignment with the trajectory necessary to keep temperature rises below 2° C. Thus, Paris will represent a modest step down a steep hill and its ultimate value will depend on whether the large emitters quickly move beyond their INDCs and embrace more challenging goals. To keep the pressure on, the U.S., China and others are advocating a regular five-year review and strengthening of INDCs, but whether this will be broadly accepted is a major question mark.

The Eiffel Tower is seen at sunset in Paris (REUTERS/Charles Platiau).

Even from a U.S. standpoint, the path ahead is strewn with obstacles. The CPP—now the centerpiece of the Obama climate strategy—could be overturned in the courts. Even if it stands, it is unclear how, using the tools available under existing law, the executive branch can go beyond the CPP and increase overall reductions to 26-28 percent of 2005 levels in the next 10 years. If current authorities prove inadequate, new legislation may be needed. But that is a highly dubious proposition in the current partisan environment. And of course the new president could scrap the CPP in 2017, walk away from the Paris agreement, and even abandon climate change as a national priority. Under any of these scenarios, the U.S. leadership role that President Obama has worked hard to nurture would be in tatters and, without American support, future international action would be immeasurably more difficult.

That many challenges cloud future progress should not detract from the impressive U.S. contribution to the Paris COP. President Obama has done what his predecessors could not or would not do—turned the U.S. into a global leader as opposed to an obstacle to progress. Whether his efforts will lead to long-term climate solutions is unknowable but the odds are better now than before he came on the scene.

Bob Sussman served in the Obama administration during 2009-2013 as co-chair of the Transition Team for the EPA and then as senior policy counsel to the EPA administrator. He was a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress in 2008, writing and speaking about climate change and energy. In 2007 he retired as a partner at Latham & Watkins. He previously served in the Clinton administration as the EPA deputy administrator. He is now on the adjunct faculty at Georgetown Law Center and Yale Law School and is a consultant on energy and environmental policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The U.S. finds its voice on climate change after two decades of failed diplomacy

November 24, 2015