In research and strategy circles around economic growth and development, the concept of “inclusive growth” is all the rage Internationally, organizations including the OECD, World Bank, World Economic Forum, Asian Development Bank, and United Nations Development Program have recently sponsored reports and initiatives devoted to promoting inclusive growth. Several foundations and corporations have also launched efforts to support inclusive economic growth, in both advanced and developing economies.

While disparate, these projects agree that inclusive growth occurs when all segments of society share in the benefits of economic growth. And they recognize that recent failures to achieve inclusive growth, especially in advanced economies like Europe and the United States, helps to explain the political and societal divisions they increasingly face.

In these societies, cities and urban regions must play a central role in promoting inclusive growth, because they represent powerful and distinctive regional economies across which the character of growth differs. Their importance, in turn, motivates our Metro Monitor report, which defines and measures inclusive economic growth across the 100 largest U.S. metropolitan areas. It tracks metropolitan progress in the areas of overall growth (size of the economy), prosperity (productivity and standards of living), and inclusion (broad-based opportunity and narrowed economic disparity). By our definition, inclusive growth occurs when a metropolitan area makes consistent progress across all three of these domains.

Widespread growth, but limited inclusive growth

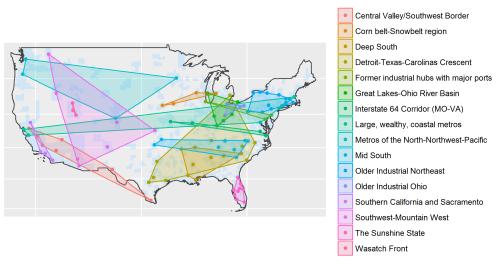

The Metro Monitor reveals that inclusive economic growth and prosperity proved elusive for most of the nation’s large metropolitan areas in recent years. All of the nation’s 100 largest metro areas added jobs and output from 2010 to 2015. Sixty-three (63) large metro areas grew by adding jobs at young firms—a sign of a healthy entrepreneurial economy. Of these 63 metro areas, 30 grew by becoming more prosperous: increasing their productivity, average wages, and standard of living. This list of 30 metro areas includes several already-wealthy tech and professional services-fueled economies, such as Austin, Boston, Denver, Minneapolis, and San Francisco. But it also includes a number of “crossroad” and “maker” economies, places like Birmingham, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dayton, Detroit, Louisville, Nashville, and San Antonio, that specialize in goods movement and/or serve as hubs for advanced manufacturing.

However, few of these places achieved inclusive growth. Measured one way—by improving the employment rate, median earnings, and relative poverty—only 11 of the 30 metro areas achieved inclusive economic outcomes: Albany, Austin, Charleston, Columbus, Dayton, Denver, Oklahoma City, Omaha, San Antonio, Tulsa, and Worcester. Similarly, only eight (8) of those 30 metro areas managed to improve inclusive economic outcomes for both whites and people of color: Albany, Austin, Charleston, Denver, Des Moines, Houston, Milwaukee, and San Francisco. The upshot, however, is that from 2010 to 2015, four (4) of the nation’s 100 largest metro areas (Albany, Austin, Charleston, Denver) achieved growth, prosperity, and inclusion that benefited a majority of workers of all races and ethnicities.

What’s behind inclusive growth

The metro areas that did manage to achieve inclusive growth of some kind shared a few common traits around recent job growth. In general, they:

- Tended to add jobs in high-skilled traded sectors like advanced business and professional services, information, and manufacturing at a rate faster than the nation

- Tended to add jobs in lower-paid types of work within those traded sectors; the traded sectors cited above typically grew less productive and/or saw their average wages decline, suggesting hiring was skewed in favor of middle- or low-skilled workers

- Balanced “traded-sector” job growth with growth of good-paying jobs for middle-skilled workers in non-traded sectors like construction, logistics, and health care

- Relied on traded and secondary sectors to fuel modest growth of typically local-serving sectors like hospitality and retail that don’t pay well, but expand employment opportunities for less-skilled workers

These patterns indicate a “high-road” economic development strategy that prioritizes both high-skilled, innovative sectors like technology and middle-skill traded sectors like manufacturing and logistics can facilitate inclusive growth. This balance may not be easy, as the number of places that accomplished it suggests. But the strategy also takes patience. The lower-skilled, lower-paid jobs generated in hospitality and retail were the last to return during this period of the recovery from the Great Recession, while better paid sectors rebounded more quickly. Often, it was only after hiring in low-paid sectors accelerated that real improvements on inclusion outcomes materialized. So metropolitan areas that continue to follow this path may join the list of economies achieving inclusive growth in the near future.

To be sure, places that achieved inclusive growth were not always the strongest performers on the measures that the Metro Monitor tracks. In contrast to high fliers like Denver and Austin, Albany performed below the metropolitan average in most indicators of growth, prosperity, and inclusion. Yet it still managed to make consistent progress from its baseline, suggesting that a metro area’s economic starting point does not preclude it from achieving near-term inclusive economic growth.

From the margins to the mainstream

To date, the concept of inclusive growth has arguably occupied think-tankers and other researchers more so than the public and private sector leaders whose actions could ultimately help realize that vision. The Metro Monitor suggests that real progress toward inclusive growth requires an informed and intentional approach, one that leverages metropolitan assets around innovation and trade to support sectors that can provide meaningful opportunities for the greatest number of workers. Moving inclusive growth from the margins to the mainstream will require widespread recognition of the economic and political imperatives, identification of concrete measures to define goals and progress, and adoption of specific policies and practices. Cities and regions are, perhaps more than ever, critical proving grounds for those efforts.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The surprisingly short list of US metro areas achieving inclusive economic growth

April 27, 2017