Recent data show the Russian economy contracted 1.9 percent in the first quarter of 2015. In this article, Sergey Aleksashenko delves into the events that led to the downturn, and what we can expect for the rest of 2015.

When the Russian ruble collapsed in mid-December last year, losing one-third of its value in three weeks, some experts forecasted a drastic downswing for the Russian economy in 2015 exceeding 10 percent of GDP. But five month later, the ruble has bounced back; the Russian stock market index has risen 25 percent since January 1st, while the Russian economy’s slide in the beginning of 2015 has been about 2 percent.

While the current crisis in some ways mirrors the 2008-2009 financial crisis, with both involving a fall in oil prices and a lack of access to foreign capital markets, this time is different. Russia suffered during the previous crisis because of a collapse in bank financing of commodities trading, hitting Russian extractive industries hard. This time, the negative trends that will play a role in the coming quarters are mainly of domestic origin, with some of them linked to the ruble collapse in December 2014. Thus, it is too soon to write off the December episode as having caused only minor damage to the Russian economy.

December’s perfect storm: The ruble collapses

A sharp drop in the ruble at the end of last year was influenced by several factors combined:

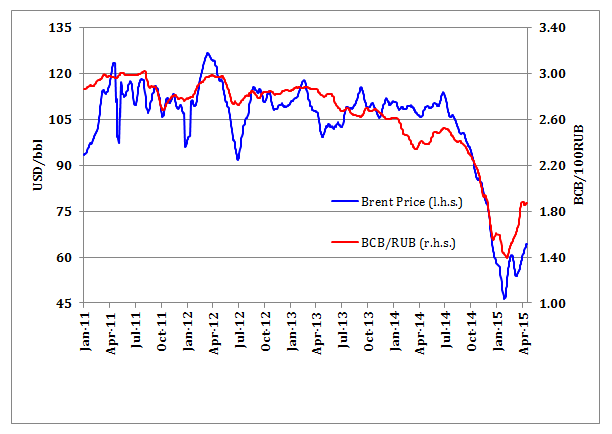

- Oil prices fell more than 60 percent from mid-summer, hitting a low of $48 per barrel of Brent. As oil represents 50 percent of Russian exports in value, that removed a significant portion of foreign-exchange supply.

Chart 1. Oil Price (USD/bbl) and Ruble Exchange Rate (BCB[1]/100RUB) in 2011-2015 (10-day moving average)

Sources: U.S. Energy Information Administration and Bank of Russia.

- Russian banks and corporations needed to buy foreign currency to pay off debt in the domestic market because Western sanctions meant they were unable to raise capital in global markets. The amount of debt to be repaid within the last quarter of 2014 exceeded $60 billion, some 15 percent of GDP for the fourth quarter.

-

By mid-November, the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), pursuing a policy of a managed ruble rate and having spent $90 billion (17.5 percent) of its foreign-exchange reserves since the beginning of 2014, decided to move to a floating exchange rate regime. But in spite of its decision, the CBR continued to sell reserves and could not give any coherent explanation for its actions, which gave rise to a high degree of distrust of the monetary authorities.

-

The state-controlled oil company, Rosneft, was due to make the largest repayment of foreign debt ($14 billion between December and February—a quarter of all payments), but did not have enough liquidity either in rubles or in dollars. To support the company, the CBR implemented a special refinancing scheme that further undermined market confidence.

-

When the ruble’s slump began to accelerate in December, the indecisive and delayed actions of the CBR were received negatively by the markets.

-

The sharp depreciation of the ruble provoked a household run on the banks. Depositors wanted to convert ruble savings into foreign currency, purchasing $22.5 billion during the fourth quarter. Furthermore, rumors about the possibility of currency regulation restrictions incentivized depositors to retain a significant portion of currency at home.

The outlook brightens

But the effects of the December storm appeared short-term and more concentrated in the financial sector; the real sector of the Russian economy seemed to be relatively stable. Manufacturing was growing due to an extensive rise in military procurement, at around 20 percent per year. Agriculture benefited from a good harvest and the food industry was buoyed by the food import embargo imposed by Russian authorities in August. Despite the decline in oil prices and other commodities, Russian producers have not reduced their exports and, thus, physical volumes of production have not suffered. Moreover, the Russian oil industry produced a record high 10.67 million barrels per day (bpd) in December, and set a new record of 10.71 million bpd in March.[2]

At the beginning of 2015, the situation in the financial markets started to improve. The ruble has bounced back to its mid-November level, and the Russian stock market index has risen 25 percent since January 1st. The most important factor was a 30 percent bounce in oil prices by mid-April that increased export revenue and boosted the business mood of many Russians who feel their success relies on oil prices. An increase by the CBR of its key rate to 17 percent provoked a jump in ruble deposit rates by up to 25 percent and stopped the outflow of deposits. Moreover, recognizing that the exchange rate had stabilized, some households began to sell foreign currency—around $4.5 billion was sold during February and March.

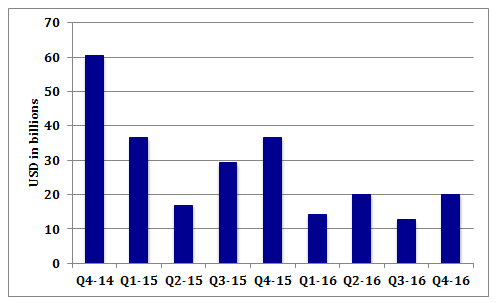

In addition, the foreign debt repayment schedule softened significantly in the first quarter—the amount due decreased by 40 percent compared to the previous quarter, to $36.5 billion. CBR data show that repayments in 2015 and 2016 will be even less, thus diminishing the future direct impact of Western financial sanctions.[3]

Chart 2. Quarterly Repayments of Russian Foreign Debt in 2014-2016 (USD in billions)

Source: Bank of Russia.

From the end of December 2014, the CBR, instead of selling foreign-exchange reserves in the open market, began to actively provide banks with loans in foreign currency that reduced demand in the market. Banks that obtained foreign currency loans repurchased Russian sovereign Eurobonds—that were used as collateral against Bank of Russia loans—compressing the spread for 10-year Eurobonds from 480 basis points in mid-December 2014 to 170 basis points in April 2015.

All this initially led to the stabilization of the ruble rate, and then—when all these factors were boosted by a powerful inflow of carry-trade capital looking for high-yield local bonds—the ruble started to strengthen rapidly. Moreover, in mid-May the CBR became uptight by the speed of the ruble strengthening and has now recommenced its currency interventions—by purchasing foreign exchange in the market—thus demonstrating its inconsistency in maintaining the ruble free-float regime.

As the situation on the forex market calmed down, it appeared that the slowdown in the economy was not as severe as anticipated. Russian President Vladimir Putin has declared that the economy has weathered the storm and is going start to recover. So is he right?

Dark skies on the horizon: A forecast for the Russian economy in 2015

While the Russian financial markets may currently be basking in a recovery few could have predicted just months ago, the Russian economy is likely to suffer from secondary effects of the ruble collapse. The key economic challenges for 2015-2016—elevated inflation, a destabilized budget and a continuing decline in investment—suggest dark clouds are on the horizon for the months ahead. Let me explain in more detail.

Inflation could remain stubbornly high

Inflation began accelerating in spring 2014 after the ruble lost 10 percent of its value over the course of January and February. Prices rose further in August 2014 after Russia imposed an embargo on food imports that reduced the supply of many products. Inflation was then further fueled by the sharp devaluation of the ruble. As a result, by April 2015 inflation had reached 17 percent. An immediate consequence was a sharp decline in household living standards. Real wages in the first quarter of 2015 decreased by 9 percent, and retail sales dropped by 8 percent compared to the previous year.

The Russian government predicts a gradual decline in inflation to around 12 percent by the end of 2015, while the CBR has kept its inflation target of 4 percent in 2017 untouched. However, these estimates make no account for three potential threats, any of which could add 1.5-2 percentage points if realized:

- A spike in food prices. Food inflation in Russia strongly depends on the harvest in Russia and the rest of the world. Food makes up about 40 percent of the country’s consumer basket and, as a grain exporter and net importer of many basic products (e.g. milk, meat, vegetable oil, sugar), Russia is quick to feel price shocks;

- A new devaluation spiral. This could come about due to the excessive strengthening of the ruble in March and April, or a decline in oil prices, or the seasonal jump in demand for foreign exchange that regularly weakens the ruble in August and September;

- The inflationary effects of the budget deficit. The use of fiscal reserves sets off the same inflationary effects on the economy as monetary financing of the deficit by the CBR. If, in 2015, the reserve fund is used to the extent accepted by law, it would be equivalent to an increase in reserve (high-power) money by about 10 percent.

Balancing the budget won’t be easy

Over the past 15 years, Russia has enjoyed a comfortable fiscal situation: rising oil prices and stable economic growth allowed it to erase the deficit, minimize public debt, increase public spending, and fuel fiscal reserves. However, the increase in expenditures distorted the structure of the budget, with accelerated growth in social entitlements (pensions and wages) and selected expenditure programs (law enforcement agencies and military spending), while expenditures on human capital and infrastructure grew very slowly.

Oil revenues make up 52 percent of the federal budget, so when oil prices slumped in late 2014 and economic growth slowed, the Ministry of Finance estimated budgetary revenues would decrease by 20 percent. At the same time, inflation and the devaluation of the ruble required increases in spending in many areas. A revision of the budget for 2015 undertaken in February and March attempted to cut expenditures by 10 percent.[4] But the actual reduction was just 2 percent, as all “savings” were used for the indexation of pensions and to compensate for cost increases for favored sectors.

Despite these measures, the federal budget deficit is still projected to reach 3.7 percent of GDP in 2015. Financing the deficit should not cause problems for the government this year, even with limited access to global capital markets, as accumulated fiscal reserves account for about 10 percent of GDP. However, a much more serious challenge awaits the government in planning the budget for 2016-2017.

Oil prices have rebounded slightly since the lows of December 2014, but one can hardly expect them to return to above $100 per barrel any time soon. Although the Ministry of Economic Development is hoping for a return to growth, the IMF, the World bank, and the EBRD say there is a high probability of continued decline of around 1 percent in 2016. This means that budget revenues will likely remain low, while a significant share of expenditures have to be indexed according to inflation (social benefits, wages, defense, etc.). In addition, the Ministry of Finance is determined to eliminate the budget deficit by 2017, which will increase pressure for additional budget cuts and will reduce the quality of services in the public sector.

The banking sector remains shaky

The collapse of the ruble and stock market last December caused serious damages for the Russian banking sector. Trying to soften the blow, the CBR extended its credit activity (both in rubles and dollars) and announced a set of measures to provide temporary relief in prudential regulation. Initially those measures were scheduled to last until mid-2015, but banking lobby is requesting their extension until the end of the year. The recovery of the financial markets in the beginning of this year made life easier for the banking sector, though since spring banks have faced a sharp deterioration in the payment discipline of borrowers. CBR statistics show that the financial position of big banks is relatively worse. That may lead to growing demands for budgetary bailouts in the near future.

Investment-led decline will continue

The Russian economy started to slow down well before the annexation of Crimea and Western sanctions—the growth rate had been steadily falling since the end of 2011. The driving force of this process has been growing capital flight and declining investment activity in the economy. After the Russian financial crisis of 1998, there was a rather stable ratio between investment growth and growth of GDP—around 2-to-1. But as investment growth in the private sector started to evaporate, the economy started to break. Moreover, due to the austerity approach of the Ministry of Finance, public investment will continue to decline. Minister of Economic Development Alexey Ulyukaev predicts the share of the budget in overall investment is going to decline from 20 percent in 2013 to less than 10 percent in 2018.

The structure of Russian imports—50 percent machinery, 25 percent consumer goods, 25 percent intermediaries—makes evident that the bulk of the balance of payments adjustment (Russian imports have contracted by 40 percent in the first quarter of 2015 compared to 2013) will coincide with a further decline in investment, which may not have a major negative impact on 2015 GDP dynamics but will certainly undermine growth prospects for the coming years.

As economists and meteorologists alike will attest, predicting the future is an unenviable task. Those of us in the business of forecasting are only ever one bad prediction away from ridicule. But the omens for Russia are not good. This year Russia may face 3 to 5 percent GDP decline, and cannot expect to return to sustainable growth any time soon. Stagnation looks likely. Throw in high inflation, and the outlook for the Russian economy for the coming years looks decidedly bleak. Keep your umbrella at the ready.

[1] Since 2005 the Central Bank of Russia has managed the ruble rate versus BCB—bi-currency basket—composed out of USD (55 percent) and Euro (45 percent).

[2] Sectorial oil and gas sanctions are applied to Arctic deep-sea and shale exploration. Those projects are currently in the earliest stages of geological study and none of them is being developed at the moment, meaning sanctions have no impact on the current volume of Russian hydrocarbon production. If sanctions remain in place, some experts argue their first effects may become visible within 18 to 24 months.

[3] Taking into account that approximately one-third of Russian corporate debt is enabled by shareholders—allowing them to minimize taxes—and is usually rolled over despite market conditions, the net repayment of the debt may reach $80 bln in 2015 and $45 bln in 2016, or 5 percent and 3 percent of estimated GDP in 2015 at the current ruble exchange rate.

[4] Those cuts were not proportional. For example, military expenditures were not touched while road construction was cut by 20 percent and all investment projects that could not be finished in 2015 were deprived of funding.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The ruble currency storm is over, but is the Russian economy ready for the next one?

May 18, 2015