Our most recent blog flagged that something odd is going on with longer-term U.S. Treasury yields. As economic activity has weakened under the weight of “Liberation Day” tariffs, longer-term yields have risen, which is quite unusual and worrying. One explanation for this odd behavior could be that a risk premium is building, as markets increasingly question the United States’ exorbitant privilege, i.e. the ability to borrow at low interest rates even as deficits are large. Indeed, as we point out today, we may have understated the severity of this problem because the rise in yields is more acute the further you go out the yield curve. Last week’s Moody’s downgrade is a reminder to get our fiscal house in order.

A building risk premium in long-term Treasury yields

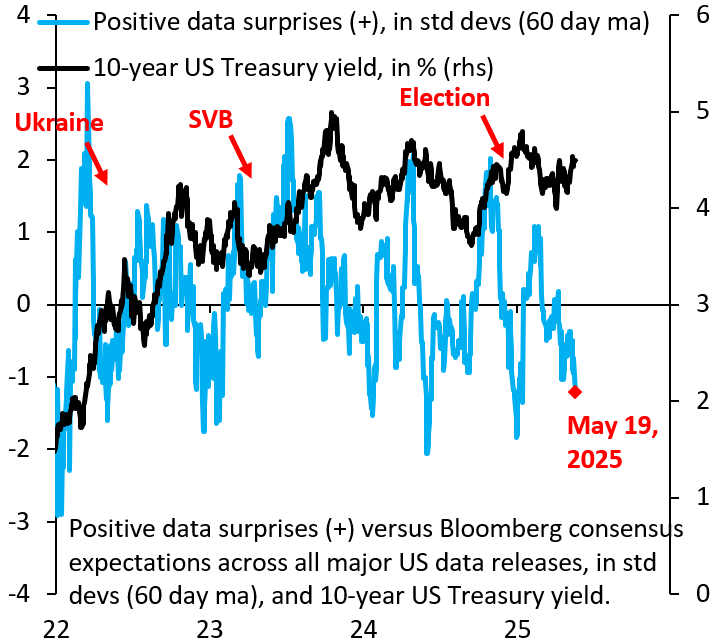

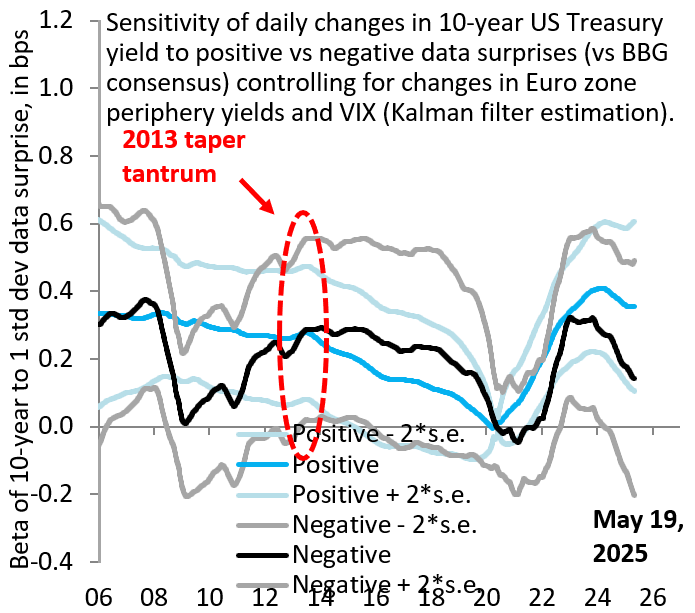

Our most recent blog constructed a data surprise index covering all major U.S. data releases. This index is positive when economic data are better than Bloomberg consensus and negative when data are weaker. Figure 1 shows this index (blue line) together with the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield (black line). Remarkably, 10-year yield has risen even as data surprises have turned increasingly negative, a divergence that started around “Liberation Day.” We estimate a Kalman filter linking daily changes in 10-year yield to data surprises, controlling for fluctuations in global risk appetite (that might cause ups and downs in safe haven demand). Figure 2 shows that negative data surprises are no longer a significant driver of Treasury yields, as markets ignore the deteriorating economy as a driver for lower yields. This is one indication that a fiscal risk premium may be building in longer-term Treasury yields.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

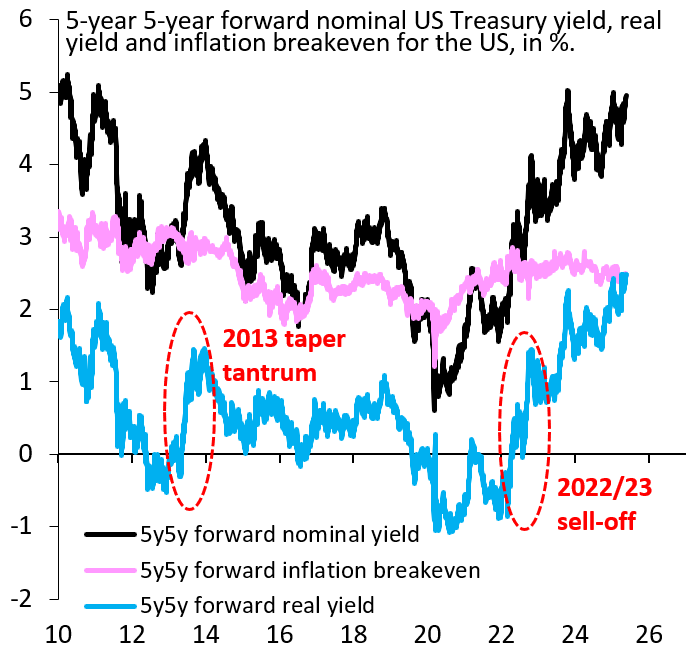

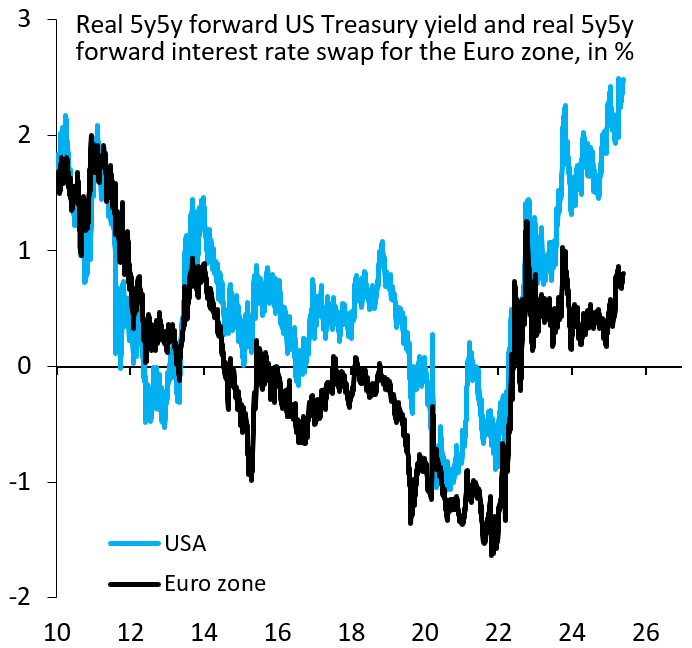

The yield curve compounds market expectations for monetary policy, which in turn are a function of expected growth and inflation. The further out the curve you go, the more important risk premia become. By way of illustration, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield now stands around 4.4%, which is below its recent high in January (just before President Donal Trump’s inauguration) of 4.8%. If instead you look at the 5y5y forward yield and decompose that into market expectations for inflation (called breakeven inflation) and the real yield (the residual between the nominal yield and breakeven inflation), this real 5y5y forward yield is now at its highest level all the way back to 2010 (Figure 3). Of course, this could reflect growth expectations, but the fact that this real yield has risen so much recently opens up the possibility that risk premia are an important driver. A comparison with an equivalent yield for the eurozone is instructive in this regard. The eurozone doesn’t have an equivalent government bond, so we use interest rate swaps to back out the 5y5y forward real rate. That rate has been quite stable, while that of the U.S. has decoupled (Figure 4), again pointing to risk premia as a possible driver.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

The fact that the 5y5y forward real interest rate is at its highest level since 2010 suggests that our Kalman filter estimation may understate the role to which market perception on the U.S. is shifting, with increased focus on the United States’ exorbitant privilege and whether that is still warranted.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The rise in long-term US Treasury yields

May 22, 2025