Ever since Western nations began to levy sanctions on Russia in response to its illegal invasion of Ukraine, a race has emerged between Russia’s efforts to amass a shadow fleet of oil tankers and efforts by the European Union, United Kingdom, and United States to sanction an ever-larger number of ships. Russia’s attempts to purchase hundreds of aging tankers—often approaching the end of their useful life—has been aided by willingness of Western shipowners to sell vessels into the Russian fleet, with an outsized contribution by EU shippers in general and Greek shippers in particular.

Russia’s shadow fleet aspirations, however, have been counteracted by an aggressive sanctions campaign by Western nations. In early 2025, the EU, U.K., and U.S. collectively initiated sweeping new sanctions on Russian ships, sharply raising both the number of sanctioned ships and the share of shadow fleet ships subject to sanctions. Below, we document these trends in detail and suggest several additional sanctions measures.

Sanctions on Russia’s shadow fleet are an especially important topic currently, because the U.S.—in an effort to negotiate an end to the war in Ukraine—is offering to lift sanctions on Russia. It is therefore critically important to understand how impactful Western sanctions are and what role they play in constraining Russia. A forthcoming blog will complement this piece by documenting how EU, U.S., and U.K. sanctions constrain shipping activity among Russia’s shadow fleet oil tankers.

The race between Russia’s growing shadow fleet and Western sanctions

Following the imposition of a price cap on Russian oil by the G7 and Australia in December 2022, Russia began rapidly amassing a “shadow fleet” of tankers that could be used to circumvent Western sanctions in hopes of trading at market prices. While Western sanctions apply to a host of oil trade services that extend beyond shipping, the presence of the shadow fleet—coupled with the emergence of the Russian insurance sector—has enabled Russian producers to more frequently trade around Western sanctions.

In an earlier post, we documented the source, by nationality, of 75 shadow fleet tankers that were sanctioned by the U.S. in January 2025. In this post, we construct a more comprehensive—though still not exhaustive—database of the shadow fleet using a variety of sources, including the European Union, Ukrainian government, and Kyiv School of Economics (KSE). Now, we can document both the growth rate and origin of Russia’s entire shadow fleet. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the true scope of the shadow fleet is likely far larger than our measure, and, as a result, our data likely overstate the proportion of sanctioned ships in the shadow fleet.

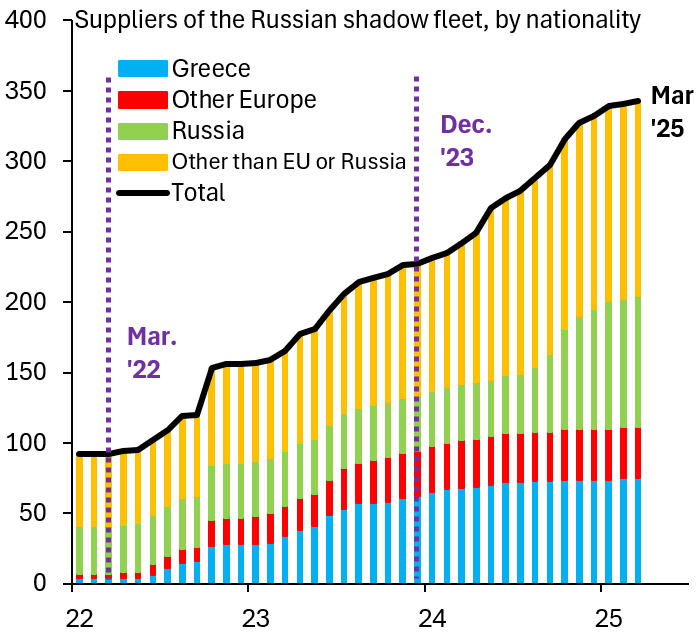

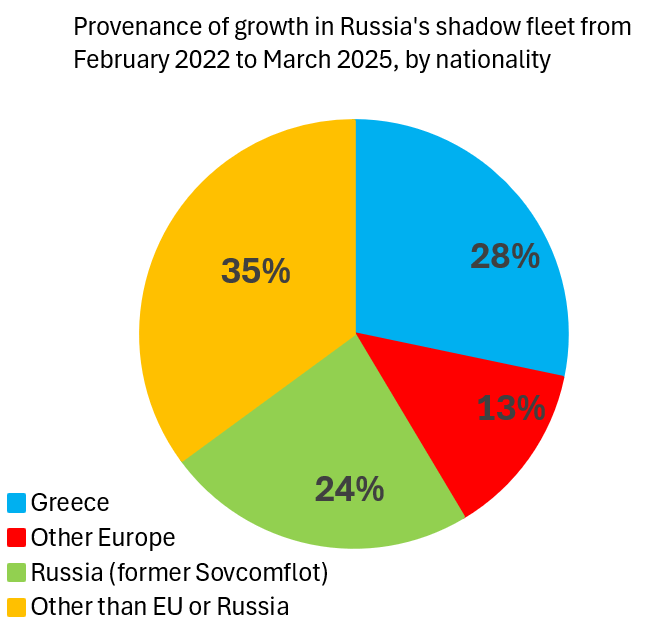

Several important lessons emerge. One, as shown in Figure 1, this shadow fleet has steadily grown from less than 100 vessels in February 2022 to 343 vessels today—with Russia adding approximately seven vessels per month over the past three years (a minority of the shadow fleet predates the invasion of Ukraine because Russia has always required at least some capacity to covertly move its oil). Two, the growth of the shadow fleet is being driven by sales from shipowners in Greece and other EU countries. As shown in Figure 2, Greece was the single largest source of shadow fleet tankers since early 2022, more than double the contribution from the rest of Europe. Not surprisingly, Russia itself has also been a substantial source of shadow fleet ships, as many former Sovcomflot ships have transitioned to the shadow fleet to help Russian exporters skirt Western sanctions.

Figure 1

Source: Bloomberg and other sources

Figure 2

Source: Bloomberg and other sources

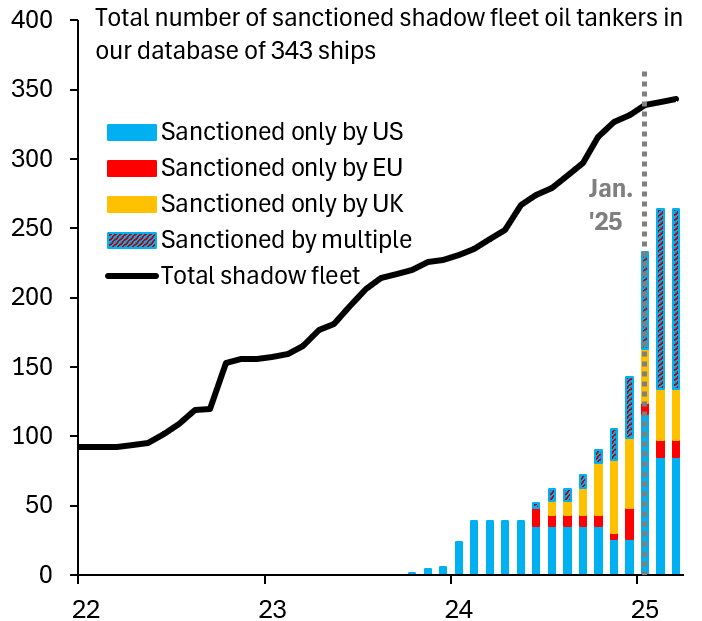

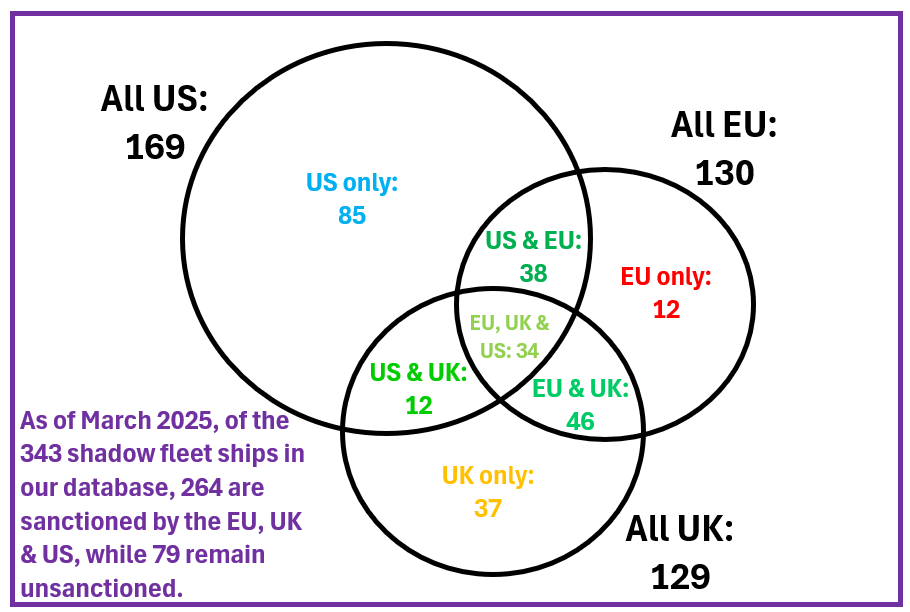

We combine these data with information on the imposition of Western sanctions, a wave of which hit shadow fleet ships earlier this year, to compare the aggregate size of the fleet to the population of sanctioned vessels. Our analysis shows that, of the 343 tankers in Russia’s shadow fleet, 264 have been sanctioned by some combination of the EU, U.K., and U.S. authorities. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, the aggressive sanctions activity in the first two months of 2025 dramatically raised the share of shadow fleet ships sanctioned by the EU, U.K., or U.S.—rising up to 77% by March of this year.

Figure 3

Source: Bloomberg and other sources

Figure 4

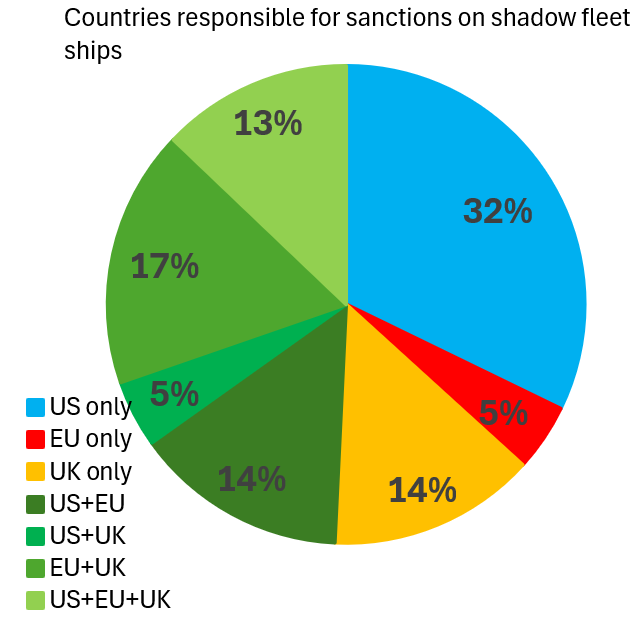

Source: Bloomberg and other sources

Importantly, too, as the total number of tankers sanctioned by at least one entity has grown, so too has the number of tankers sanctioned by multiple Western entities. As shown in Figure 4, by March 2025, approximately half (49%) of sanctioned shadow fleet ships were sanctioned by multiple sanctioning authorities. As Figure 5 shows, of the 264 tankers in our database that are currently sanctioned, 130 are sanctioned by multiple countries (38 are sanctioned by the U.S. and EU, 12 by the U.S. and U.K., 46 by the U.K. and EU, and 34 are sanctioned by all three) while 134 tankers are only sanctioned by a single entity (85 are sanctioned by the U.S., 37 by the U.K., and 12 are sanctioned by the EU). Of the 343 ships in Russia’s shadow fleet, there are still 79 that are currently unsanctioned by the EU, the U.K., or the U.S.

Figure 5

Policy implications for further sanctions

Overall, the data presented here suggest that tankers supplied by EU shipping companies, especially of Greek origin, were instrumental in aiding Russia’s quest to acquire a massive shadow fleet. However, aggressive actions in early 2025 by the EU, U.K., and U.S. successfully captured a large share of the shadow fleet. In light of this analysis, we propose several additional measures to be taken: (i) Sanctioning bodies should prohibit the sale of Western tankers to buyers who might be acting as middlemen for Russia’s shadow fleet; (ii) overlap of sanctions should be maximized, so that—ideally— the U.S., the U.K., and EU sanction vessels jointly in all cases; and (iii) the 79 ships in our database that are currently unsanctioned should be sanctioned. We will publish a complete list of opportunities for further sanctions in a future post.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank Liam Marshall, a senior research assistant at Brookings, and Elijah Sheets, an undergraduate student at Southern Methodist University, for excellent research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The race to sanction Russia’s growing shadow fleet

April 25, 2025