The productivity “paradox” reflects, among other things, major and widening differences among economic sectors, and the people who work in them. High skilled sectors—and their workers—receive high returns to technological innovation and other contributions associated with those skills. These include an ability to anticipate and plan for the future, and to adapt and innovate in accordance with that. In contrast, low-skilled workers in traditional blue-collar jobs are caught in an economy of the past that is rapidly fading away. The sectors that they work in, ranging from coal mines to auto industries, are either being made obsolete by technological innovation and/or are adopting new production chains, which are global in scale. Not only are workers in these industries losing in terms of wage levels (both absolute and relative), but they are also losing their identities, their security, and their way of life. As a result, they lack the capacity to think about and plan for the future, much less to invest in it.

While productivity and innovation produce aggregate economic gains, those left behind experience significant costs, which extend well beyond the monetary realm. My research attempts to estimate these non-monetary costs in the broader dimensions of human welfare. I use traditional measures of income inequality as a point of departure and then use well-being metrics to estimate inequality in beliefs, hope, and aspirations. These metrics include evaluative measures, such as life satisfaction and optimism about the future, and experienced or hedonic measures such as smiling and experiencing stress or anger the previous day.

I find that the high costs of being poor or downwardly mobile in the U.S. are more evident in stress, insecurity, and hopelessness than in material deprivation. Most of these individuals are not able to choose the kinds of lives they want to lead and are instead experience high levels of stress related to insecurity and circumstances beyond their control. Not surprisingly, they are also typically much less optimistic about their futures, as they lack the capacity to plan for or conceive of those futures. In contrast, individuals who believe in their futures are much more likely to invest in them.

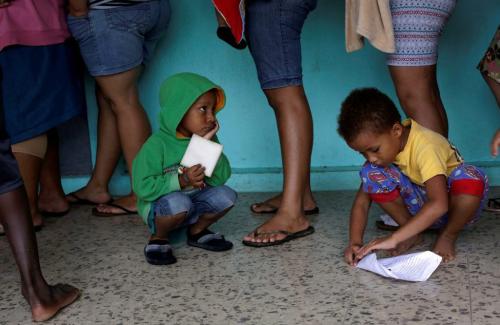

One stark marker of this lack of hope among the U.S. poor is that they are significantly less likely to believe that hard work will get them ahead than are the poor in Latin America (in contrast, the rich in the U.S. are more likely to answer this question positively than are the rich in Latin America). The poor in the U.S. are also much more likely to experience stress the previous day than are the poor in Latin America, and much less likely to have smiled the previous day. The gaps between the scores of the rich and poor on all of these markers are also much greater than the gaps between the rich and the poor in Latin America.

The markers of hopelessness in the U.S. are also evident in income, education, and employment data; in differences in mortality, marriage, and incarceration rates across the poor and the rich; and in other signs of societal fragmentation. Yet trends in hope and well-being are not uniform across all poor cohorts. I find, for example, remarkable levels of optimism among poor blacks (and poor Hispanics, but not as high), in contrast to deep desperation among poor whites.

Our metrics of desperation, stress, and anger match closely with the rising levels of premature mortality across cohorts (concentrated among uneducated whites, as in the mortality data) and places. Desperation, hopelessness, stress, and anger are all higher in rural areas and small towns in the heartland—which are most vulnerable to the productivity paradox—and lower in the larger coastal cities, mirroring the mortality rate patterns. My colleagues and I also find that places that are more racially diverse (assessed as percent of black and Hispanic respondents) are, on average more satisfied with life and more optimistic about the future, as well as less stressed and angry. Racial diversity also links to a higher percentage of respondents who exercise and a lower percentage of those who smoke. Again, these traits also correspond with urban areas on the coast with lower rates of premature mortality (and more vibrant, diverse economies).

Other trends in the data suggest inter-related explanations for what is going on, again with relevance to productivity trends. One is the significant increase in reliance on disability insurance in the past two decades, rising from just under 3 percent of the working age population to almost 5 percent for men, and from roughly 1.3 to 4.5 percent for women.[1] While it is particularly concentrated in former coal mining regions, it extends beyond them and mirrors reported pain and high concentrations of prime age men out of the labor force. While disability insurance provides an important and often life-long safety net for many workers and their families, it also introduces additional barriers to labor force participation. Potential recipients cannot participate in the labor force during the wait time for approval for disability, a period that can last up to two years. It is difficult to imagine that many of this cohort will be able to participate in the high skilled, high technology economy.

Other issues related to reliance on disability may also play a role in ill-being, such as via the loss of identity that workers experience when they can no longer can participate in the jobs—and daily interactions—they have held over much of their life course. Our data show patterns across the places (states here) with the highest rates (and increases in rates) of reliance on disability insurance and average levels of stress, anger, and worry. Reliance on disability insurance and reported pain, meanwhile, tend to be gateways into the increasing levels of addiction to opioids and other drugs. The secular trend of prime age (25-54 year old) males dropping out of the labor force complements the increase in reliance on disability insurance. Nicholas Eberstadt (2016) projects that 25 percent of that cohort will no longer be in the labor force by mid-century (compared with 15 percent today).

A potentially reinforcing factor in this cycle is that these same cohorts, who are disproportionately located in remote rural areas, are less likely to have social connections outside their locales. In general, social interactions are likely to be more common in densely populated diverse urban places. A recent study from Tisch College finds that the majority of rural youth live in “Civic Deserts,” which are defined as places characterized by a dearth of opportunities for civic and political learning and engagement, and without institutions that provide opportunities like youth programming, culture and arts organizations, and religious congregations. These same areas are also far less likely to have access to broadband internet than are urban ones, which not only limits social connections but also information about jobs outside their immediate environs. Sadly, all of this reinforces a picture of an entire part of the economy—and society—fading away from the mainstream.

What next?

What explains lack of hope among the U.S. poor? Inadequate access to health insurance and stable employment play a role, but so do the increasing gaps between the lives of the rich and the poor. These inequities may lead to more inequality in the future; individuals who do not believe in their futures are unlikely to invest in them. Yet there are also major differences across poor cohorts, as noted above. Why are blacks and Hispanics so much more optimistic? Why are they more resilient to negative shocks and less likely to report depression or commit suicide, as some psychologists find? Expectations and experiences matter. Minorities are making gradual and hard-won progress on many fronts, such as education and life expectancy. Poor and blue-collar whites have experience downward mobility, at least relative to their parents, and are more likely to have the kinds of jobs that are vulnerable to technological change, and to have stronger historical links to the identity of those jobs than are migrants or minorities. There are similarities with the situation with Europe, although it is not as extreme (at least in the arena of premature mortality). In both contexts, the native working class populations suffer significant challenges, while the places that more diverse – both economically and demographically – seem to be more adaptable to new alternatives to manufacturing jobs, such as in the health sector.

It is obviously not possible to turn back the clock on technology, innovation, and new forms of productivity. At the same time, it is critical to understand the plight of those left behind. In the absence of active solutions, they will become even more desperate, with support for extremist politicians likely to increase. This is a complex problem, and there are no magic bullets. Solutions extend across the educational, safety net, and re-training/re-location realms. My research highlights the important role of well-being metrics in identifying and monitoring trends in hope, desperation, and misery as a first step to understanding the problem and its patterns across people and places. My new research is exploring policies—including experimental ones—in which hope is an important channel in improving outcomes. Yet there is a long way to go in our understanding. Introducing hope, for example, is likely easier among the very poor in poor contexts (where my experiments in Peru are) than among downwardly mobile cohorts in very wealthy contexts like the U.S. or Europe. Making progress, though, is essential to sustaining integrated global economies and market democracies.

[1] Details on SSDI are from Social Security Advisory Board data, available at: http://www.ssab.gov/Disability-Chart-Book.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).