Africa needs significant financing in order to meet its ambitious sustainable development goals. While domestic financing sources such as tax revenues have increased, they are not sufficient to fill the continent’s financing gap. As a result, a number of governments are accessing international markets to complement domestic financing. However, as seen in the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis or more recently in the European crisis, external financing comes with risks.

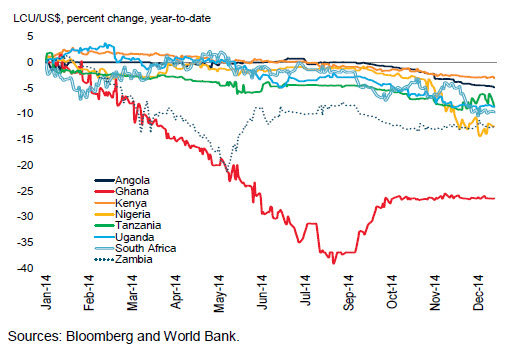

In a useful and timely exercise, Overseas Development Institute (ODI) assesses these risks and finds that the depreciation of local currencies with respect to the U.S. dollar in 2014 is threatening sub-Saharan African governments’ ability to repay the bonds to investors. But is that really true? Before 2006, only South Africa was the only sub-Saharan African country to issue a foreign-currency denominated sovereign bond. From 2006 to 2014, at least 14 other countries have issued more than $15 billion in international sovereign bonds. Unfortunately, the increased indebtedness of these countries increases their vulnerability to economic shocks. As a number of African currencies such as the Ghanaian cedi and the Nigerian naira have been depreciating recently, servicing debt denominated in the U.S. dollar becomes even more expensive (Figure 1). But how much riskier has African sovereign debt become as a consequence of currency depreciation?

Figure 1. African currencies and sovereign bond interest rate spreads

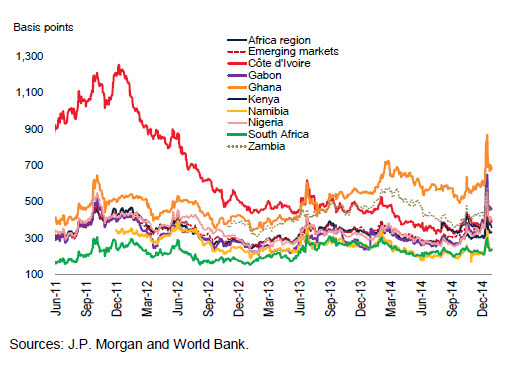

The ODI report uses a stress test exercise to find that “the foreign exchange rate risk of sovereign bonds issued by governments in sub-Saharan Africa in 2013 and 2014 is threatening losses of $10.8 billion—a value equivalent 1.1% of the region’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).” African countries face such a risk because they have borrowed in U.S. dollars but typically earn a large share of their revenues in local currencies. If local currencies depreciate with respect to the U.S. dollar, borrowing countries experience a loss of value of their local currencies and have to raise more local currencies to pay back their U.S. dollar-denominated debt. This additional amount (expressed in U.S. dollars or as a percent of GDP) is the FX impact in the ODI calculations. Figure 2 below (from the ODI report) shows the additional amount that ODI estimates countries would have to raise in order to service their sovereign bonds following a depreciation of their local currencies. For instance, following a 30 percent depreciation of the Angolan kwanza with respect to the U.S. dollar, the authorities in that country would have to raise an additional $451 million to service their $1,503 million debt, an amount equivalent to 0.36 percent of the Angolan GDP in 2013.

Figure 2. “Stress test” scenario of foreign exchange risk, using worst actual currency moves in the region (30 percent depreciation with respect to the U.S. dollar)

Source: Overseas Development Institute.

Allow me to disagree with these numbers.

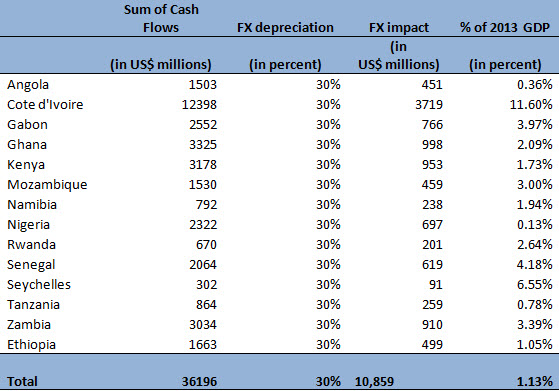

My first concern is that the “$10.8 billion loss” assumes 30 percent devaluation based on “the worse actual currency moves in the region in 2014 (which were for Ghana)” and “applies the devaluation to all currencies.” This assumption overestimates the impact of the foreign exchange shock. Take Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, and Senegal—which together account for about 47 percent of the total estimated FX impact. These three countries share a currency (the CFA franc), which is pegged to the euro and which has only been devalued once since 1960 (a 50 percent devaluation against the French franc in 1994). As a result, movements of the CFA franc with respect to the U.S. dollar mirror exactly movements of the euro with respect to the U.S. dollar, and, although the euro has depreciated against the U.S. dollar, it has lost about 18 percent from early 2014 to date (which includes the impact of the Greek elections). Other currencies, apart from the Zambia kwacha and the Nigerian naira, have not lost more than 10 percent. Markets are (so far) somewhat discriminating between different African credits and the differences in the level of spreads among African sovereign bonds incorporate their differentiated risks, including exchange rate risk. A more realistic scenario would have been to use the worst actual currency moves for each country rather than that of the Ghanaian cedi. In Figure 3, I have quickly re-estimated the FX impact using such a scenario and find an average 15 percent devaluation which leads to a FX impact of about $6.5 billion or 0.68 percent of GDP. These figures are lower than the ODI estimates of $10.8 billion or 1.1 percent of GDP.

Figure 3. “Stress test” scenario of foreign exchange risk, using worst actual currency moves for each country and comparison with ODI findings

Source: Overseas Development Institute and author’s calculations.

My second concern is that the paper does not account for the net present value of cash flows. The paper’s assumption again overestimates the impact of the devaluation as it ignores the time value of money ($100 now should be worth more than $100 in 10 years because you can invest the money in low risk asset and earn interest). Simply adding the cash flows of the bonds will lead to much higher value than discounting them, and the longer the maturity of the bond, the higher the difference with the present value of the cash flows. Take Côte d’Ivoire, which accounts for about one-third of the FX impact estimated in the paper. It has issued two bonds with tenors of 22 year and 10 year, respectively. To estimate the present value of cash flows, I assume that the interest rate spread of Côte d’Ivoire is about 400 basis points (4 percent) over a U.S. 10-year treasury yield of 2.25 percent and calculated a present value of $5.8 billion, which is almost half the figure of $12.4 billion used in the ODI paper. Applying a devaluation of 18 percent instead of 30 percent to the Ivorian bonds yields an FX impact of about $1 billion (or 3.3 percent of GDP) rather than $3 billion (11.6 percent of GDP). Even applying a (not so realistic) devaluation of 30 percent, leads to an FX impact of about $1.7 billion—about half what the paper finds. So just by focusing on Côte d’Ivoire, the estimated FX impact falls from $10.9 billion (1.13 percent of GDP) to about $5.3 billion (0.55 percent of GDP).

My third concern is that the paper assumes that the effect of the devaluation is permanent. Implicitly, the ODI paper assumes that when a government has issued a 10-year U.S. dollar denominated bond and that the local currency depreciates with respect to the U.S. dollar, it will bear the resulting higher debt servicing cost for 10 years. Instead, it is more reasonable to assume that the government will not remain idle for 10 years and will attempt to reduce the cost of debt repayment. For instance, the government could earn more U.S. dollars over a year or so if the value of exports rises following the depreciation of the local currency which makes them cheaper to foreigners. Such an automatic stabilizer is rightly mentioned in the paper but it is not taken into account in the stress test scenario. In practice, therefore, the government will focus its risk analysis on a shorter-term horizon than the maturity of its debt. For instance, the government will focus on a one-year horizon, in which cash flows are at risk from a depreciation of its currency.

In conclusion, the paper is timely as it brings attention to the risks stemming from the increased indebtedness of African countries, and I found it quite useful in highlighting the importance of adequate sovereign debt management at this stage However, it is not yet time to sound the alarm on these risks. Rather it is time to check the fire alarm and make sure that African governments can properly and rapidly identify, measure, and manage the risks from their increased external indebtedness. A recent paper entitled Africa Debt Rising by the Africa Research Institute reaches a comparable conclusion.

Rebalancing the Risks from U.S. Dollar External Debt to Local Currency Domestic Debt

In fact, there is some good news. African debt management offices have benefited from increased technical assistance from the World Bank, the IMF, and other bilateral partners such as the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Technical Assistance, allowing them to strengthen their institutional capacity to manage public debt and providing them with analytical tools.

However, the work agenda is far from being finished. Indeed, beyond foreign exchange risk, there is a real risk that African countries may become so dependent on external debt that they may not sufficiently develop their local debt markets. This type of “structural risk” is high because in many countries U.S. dollar-denominated external debt is cheaper than local currency-denominated domestic debt. Ghana’s experience is a case in point. In January 2013, its government could pay about 4.3 percent on a 10-year borrowing in dollars. However, when borrowing in local currency domestically, the interest rate was at least 23 percent on 3-month Treasury bills. After inflation differentials are taken into account the difference between the U.S. dollar and local currency borrowing costs reaches 10.6 percent (and 5.4 percent taking into account currency depreciation).

This wedge is due in part to changes in the policy environment—monetary policy was tightened in 2012, and the fiscal deficit increased to about 10-11 percent of GDP. But the wedge was also due to a low external cost that reflects foreign investors’ search for yield. The difference also reflected underdeveloped domestic debt markets with an investor base dominated by banks—which raised domestic borrowing costs—and the likely effects of restricting foreign investors from buying short-term domestic government securities (with a maturity of less than three years).

Two years later, the economic situation has deteriorated significantly, leading the country to request an IMF program. However, Ghana’s deteriorating fundamentals have not led to a loss of market access, but have resulted in higher borrowing costs. In particular, in September 2014, Ghana was able to raise $1 billion for a 12-year bond paying a coupon of 8.125 percent at the same time it was negotiating an IMF program. Ghana is now paying the highest spread among sub-Saharan issuers at about 550 basis points (or 5.50 percent) over U.S. Treasury bonds and has the lowest credit rating.

The lesson from Ghana’s experience is that African countries should pursue a two-pronged approach. The first priority should be to improve fiscal policy and strengthen debt management. The second priority should be to develop local capital markets. Armed with strong fiscal and debt management policies, African countries will be better place to opportunistically exploit the boom-bust cycle of international interest rates, tapping international markets when borrowing costs fall and relying on local markets when such costs rise.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The foreign exchange risk of African sovereign bonds: Not yet time to sound the alarm!

February 13, 2015