For the world’s poorest people, climate change does not announce itself in parts per million. It arrives as a ruined harvest, a flooded shopfront, or lost learning as children are kept out of school. The most consequential climate-policy question for developing economies, therefore, is not just how much carbon the world emits, but also how quickly people, firms, and governments can prepare for shocks, recover from them, and learn to do better next time.

The weight of weather

In the world’s poorest regions, the weather has become a relentless source of the divergence in living standards between wealthy and poor nations. A failed monsoon, a heat wave that refuses to end, a river that swallows a village—each year brings a reckoning that wealthier nations seldom experience. Since 1960, mortality per climate disaster has been six times higher in low- and middle-income countries.

Wealthier nations rebuild; poorer ones start again from nothing. The difference lies in layers of protection that take generations to build: savings, sturdy homes, social safety nets, and systems that sound warnings well before storms arrive.

Those layers—household income, reliable information, private insurance, public infrastructure, and social interventions—decide whether a shock leaves a permanent scar. Call them the Five I’s of Resilience. When put this way, this might seem obvious. Yet too often, resilience is reduced to buttressing public infrastructure and social assistance. In reality, it is something more intricate: a web of choices, each thread reinforcing the others.

Income: The first shield

When the water rises or the wind tears through fields, a swift recovery is often a matter of wallet size. Income becomes a determinant of resilience.

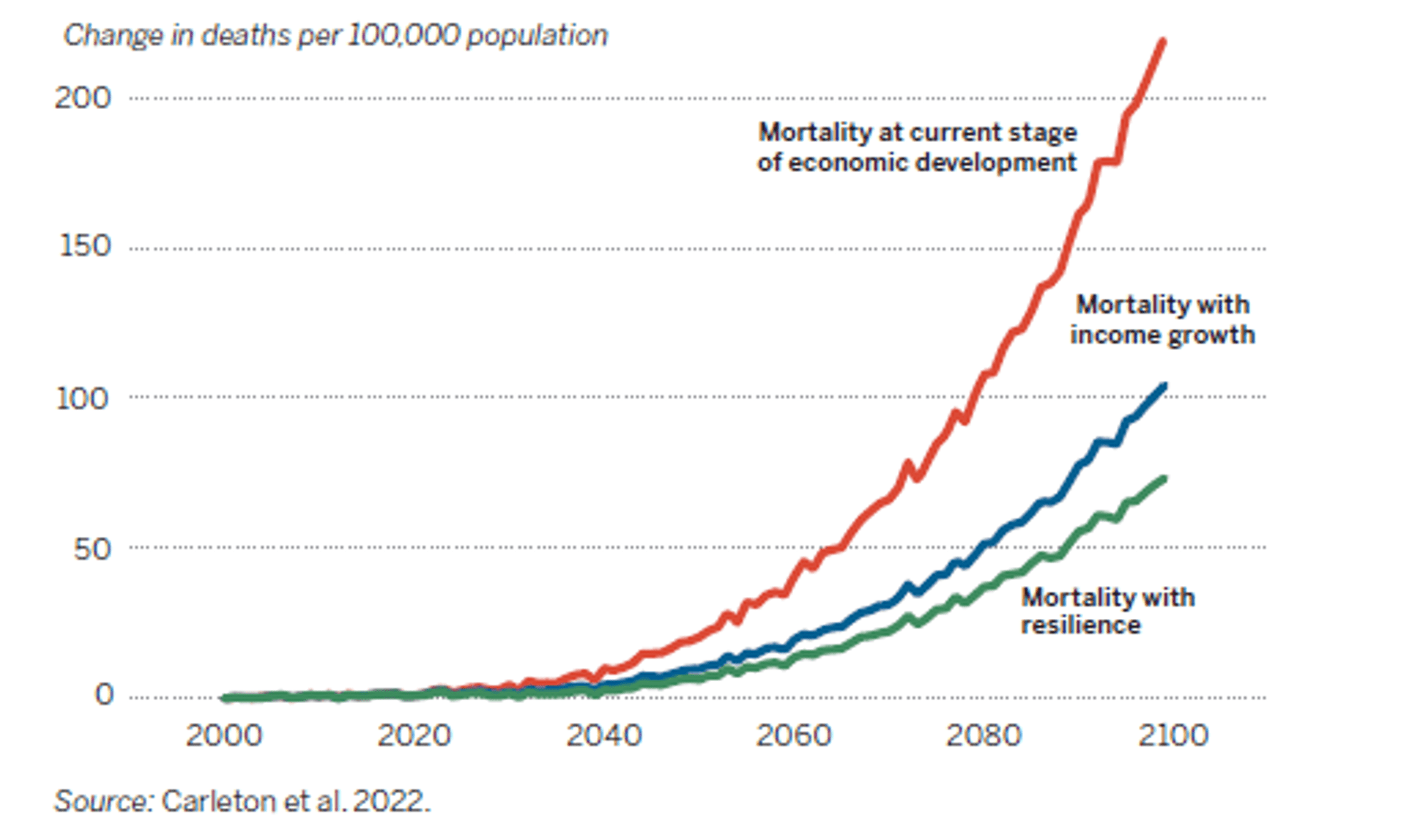

By the end of this century, roughly 80% of humanity’s capacity to withstand rising temperatures (measured by falling death rates) will come from higher per-capita income (Figure 1). The remaining 20% will come from what experience teaches: How people, firms, and governments learn to rebuild better after every shock.

Figure 1. Income growth is the main source of climate resilience

A 10% rise in global per-capita income could spare around 100 million people from climate vulnerability. Bangladesh shows what that means in lives saved. Cyclone Bhola in 1970 killed half a million people. Four years later, floods and famine claimed 1.5 million more. By 2019, when Cyclone Sidr struck with similar force, the death toll was about 3,500. In those decades, Bangladesh’s per-capita income rose nearly fourfold, from $400 in 1974 to $1,564 in 2019. Growth bought resilience.

Information: Turning fragility into foresight

Before the storm comes data. When farmers know what nature intends, they harvest early, move livestock, reinforce walls. When they do not, they wait—and waiting kills.

Uncertainty breeds paralysis. Without credible forecasts, people cling to habits that have already failed them. Governments overspend on defenses while underinvesting in warnings.

Accurate and accessible data (modern weather stations, flood maps, timely alerts) turn peril into something people can prepare for. The returns are immense: The benefit-cost ratio of an early-warning system is about 9 to 1. A single day’s notice can cut damages by a third. In India, reliable monsoon forecasts have reduced losses and raised farm profits.

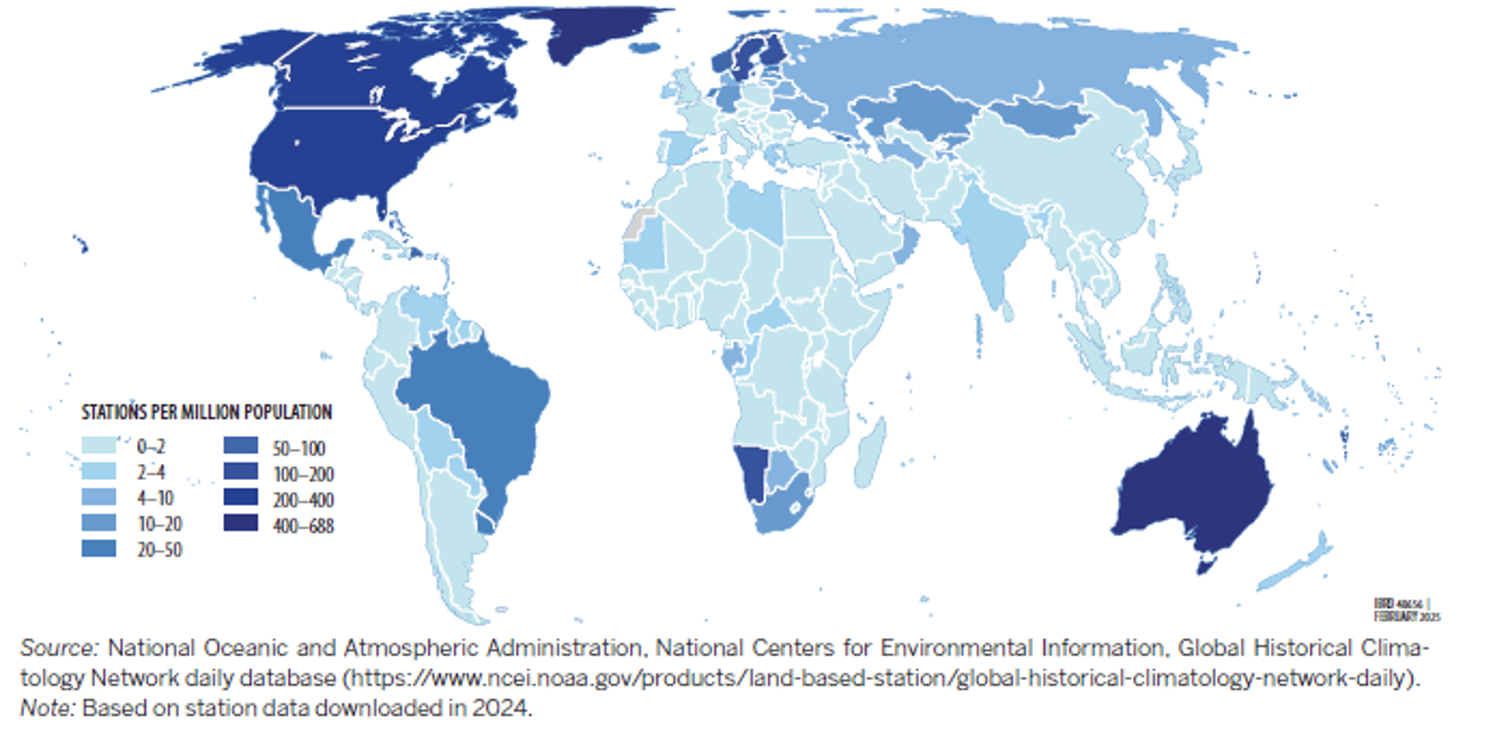

Figure 2. Sub-Saharan Africa remains an information desert with very few weather stations per capita

Yet where the danger is greatest, the systems are the weakest. Sub-Saharan Africa has 1.5 weather stations per million people; India 3; Germany 13; the United States 217 (Figure 2). In some low-income countries, a one-day forecast is less accurate than a seven-day outlook in rich countries. Closing these gaps (observations, modeling, communication) multiplies the impact of other investments in resilience. And by attaching probabilities to states of the world, reliable information allows insurance markets to develop.

Insurance: leaving less to chance

When insurance works, recovery is faster and risk-taking becomes productive. When it fails, the poor fall into debt and destitution. In 2020, developing countries sold 265 million insurance policies (95% of them in China and India) where coverage is subsidized or tied to loans. Elsewhere, insurance remains scarce. Index-based products (payouts triggered by rainfall, river levels, or pasture greenness) are spreading through satellites and mobile money, yet adoption remains thin. Costs are high, payouts sometimes miss real losses, and insurers avoid true catastrophes.

Governments can tilt the balance by improving data, enforcing transparency, and offering catastrophic reinsurance while preserving honest prices. In the Horn of Africa, satellite images now trigger payments to herders before drought kills their livestock—a shift from crisis relief to prevention, from desperation to design.

Infrastructure: Strength that lasts

Many governments still equate resilience with seawalls and post-disaster aid—a framework built of cement and hindsight. That approach drains resources from the very systems (growth, data, insurance) that make those walls worth building.

Protective works can even invite danger. Jakarta’s proposed seawall may shield the city today but—unless accompanied by the other measures discussed here—could double its long-term social costs by concentrating people behind it and delaying migration from flood-prone zones. Climate volatility magnifies the risk: Infrastructure built for yesterday’s probabilities can crumble under tomorrow’s storms.

Pipes, pylons, and pavements endure when guided by data and zoning that account for risk. The result is a bridge built in the right place, according to the right standard, and under sound insurance and regulation.

Interventions: Adaptation from within

Even with growth and good data, some blows are too heavy to bear alone. Social protection cannot stop the storm, but it does make coping easier.

Assistance in the form of social protection is often needed to protect the poorest, but resilience can and should grow from within. In northern Kenya, herders once relied on cattle—the first to die in a dry spell. As rains grew erratic, they shifted to camels, which can endure weeks without water. This transformation was shaped by traders and markets that expanded demand for camels and their milk. Kenya’s camel herd grew from 800,000 in 1999 to 3.6 million by 2022: an example of adaptation as enterprise.

The World Bank’s De-risking, Inclusion, and Value Enhancement of Pastoral Economies (DRIVE) initiative builds on this logic. Using mobile platforms and index insurance, DRIVE delivers payouts before losses mount, helps protect breeding stock, and enables herders to shift toward sturdier livelihoods.

Building readiness from the ground up

Figure 1 suggests that when the objective is the betterment of the human condition, it is helpful to think of resilience as consisting of two parts economic development and one part climate adaptation. This ratio might change by region, but the prioritization of policies does not. The Five I’s—Income, Information, Insurance, Infrastructure, and Interventions—provide both a checklist and the prioritization of policies:

- Income gives families the means to recover and invest.

- Information transforms uncertainty into choice.

- Insurance finances recovery and sustains risk-taking.

- Infrastructure protects lives when designed for change.

- Interventions prevent irreversible loss while preserving flexibility.

For frequent, smaller shocks, income and information should lead the way. For rarer, larger ones, insurance and infrastructure should do the heavy lifting. In the poorest regions, every layer matters.

Governments cannot insure every citizen against every loss, of course. Their real task is to cultivate the conditions for resilience: inclusive growth, rigorous data, and well-functioning markets. International institutions should measure climate spending not by kilometers of seawall but by whether people and firms have the knowledge and tools to manage risk.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The five pillars of climate resilience

November 17, 2025