The paper summarized here is part of the spring 2021 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. Research findings are presented in a clear and accessible style to maximize their impact on economic understanding and policymaking. The editors are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Northwestern University Professor of Economics Janice Eberly and Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Harvard University Professor of Economics James Stock. See the spring 2021 BPEA event page to watch paper presentations and read summaries of all the papers from this edition.

Reducing pre-trial detention by eliminating cash bail would generate significant economic returns for accused individuals and likely also their families and communities, suggests a paper discussed at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) conference on March 25.

The authors—Will Dobbie and Crystal Yang of Harvard University—note that more than 10 million people are arrested each year in the United States and that, at any point in time, roughly half a million are in pre-trial detention. They cite “the all-too-common stories of arrested individuals who, despite being first-time offenders accused of low-level crimes, spent months in pretrial detention and faced subsequent long-term damage in the form of family separation, work interruption, and loss of housing, or even death.”

“Many of these harms can result even when the period of incarceration is brief and even if individuals are not ultimately convicted of any crime,” they write in The economic costs of pretrial detention.

To assess the effects of pre-trial detention on individuals, particularly younger people, Dobbie and Yang looked at employment and income of people arrested in Miami and Philadelphia from 2007 to 2014. Reviewing evidence in previous research, they note that pretrial detention decreases the probability of employment three to four years after the bail hearing by 9.4 percentage points. And, under a series of assumptions, they estimate that defendants detained pre-trial lost $29,001 in income on average over a lifetime compared with defendants who weren’t detained pre-trial.

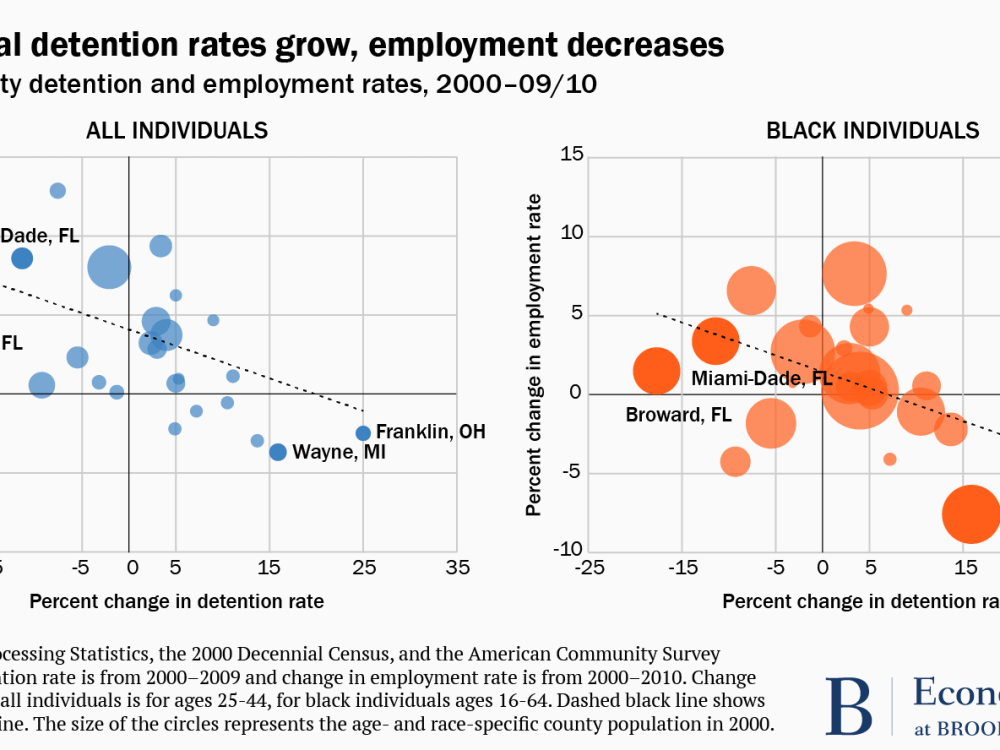

Using 1990-2009 county-level data (the most recent available) from a U.S. Department of Justice survey, they show that counties with higher detention rates also experience, on average, higher poverty rates and lower employment rates, particularly for Black individuals. And, the authors present evidence showing reduced economic mobility for children in counties with higher pre-trial detention rates.

Reducing pre-trial detention from 38 percent (the figure for felony defendants in 2009) to 10 percent—through reforms such as the elimination of cash bail—would produce substantial economic benefits, they argue. If money bail were eliminated, they estimate that up to 2.8 million fewer people would be detained per year. (Some defendants would continue to be detained on the grounds that they are dangerous.) And, they estimate that eliminating money bail could increase aggregate U.S. income by up to $80.9 billion per year.

“If you want to improve economic outcomes … you don’t want to just look at changing labor-market policies, you also want to think about reforms to criminal-justice policies,” Yang said in an interview with Brookings. “We think focusing on the pre-trial system is a good place to start.”

acknowledgments

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper. Becca Portman assisted with data visualization.

Citations

Dobbie, Will and Crystal Yang. 2021. “The Economic Costs of Pretrial Detention.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 251-291.

Miller, Conrad. 2021. “Comment on ‘The Economic Costs of Pretrial Detention’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 292-299.

Wolfers, Justin. 2021. “Comment on ‘The Economic Costs of Pretrial Detention’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 299-312.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are currently not officers, directors, or board members of any organization with an interest in this paper.

Disclaimer

The views expressed by the authors, discussants and conference participants in BPEA are strictly those of the authors, discussants and conference participants, and not of the Brookings Institution. As an independent think tank, the Brookings Institution does not take institutional positions on any issue. Please contact Haowen Chen ([email protected]) if you have any questions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).