Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

Introduction:

The concept of strategic balance was developed by the two superpowers in the context of East-West nuclear contestation during the Cold War. It was primarily inspired by the advent of nuclear weapons, though it also drew on the unique history, particularly of the two world wars and the massive destruction suffered by major powers.

Strategic balance was premised on three interlocking concepts:

First, the elaboration of nuclear deterrence with the objective of preserving a no nuclear war scenario between the nuclear weapon states; the superpower allies and others accepted this, sometimes reluctantly.

Second, the management of deterrence among major power and their allies through a number of bilateral (US-Soviet agreements), plurilateral (NATO, Warsaw Pact and CSCE) and multilateral (United Nations Security Council) institutions as well as arms control (SALT, START etc.) and, if necessary, even disarmament (ABM and INF)

Finally, the construction of a non-proliferation regime (Atoms for Peace, NPT etc.) to preserve the nuclear deterrence order, strategic balance and prevent new challengers. There was very little faith that strategic balance and related stability could be preserved at the nth country level.

Post-Cold War:

However, in the post-Cold War era this traditional concept of strategic stability began to erode on account of at least three factors:

First, the collapse of the Soviet Union also meant that its ability to keep up with the US and maintain strategic stability was severely compromised. This was coupled with the inability to fundamentally transform the relationship with Russia from an adversarial to that of a quasi-ally. At the same time the US also sought absolute security, instead of mutual insecurity, which further weakened strategic stability.

Second, the quest for absolute security also led the US and its allies to put greater emphasis on defence rather than deterrence. A related factor was the diminishing role of nuclear weapons and the enhancement of conventional capabilities over the nuclear arsenal. This became possible at the end of the Cold War on account of technical, financial and managerial capabilities.

Third, the emergence of a number of nuclear armed and nuclear capable countries, particularly outside the East-West framework and notably in Asia (China, DPRK, India, Israel, Pakistan), also challenged the traditional notion of strategic balance and strategic stability in three ways.

The Asian Challenge:

First, the geopolitics of Asia in general and South Asia in particular (common disputed borders, short distances blurred the distinction between strategic and tactical) meant that strategic balance and stability could not be easily adopted even if there was such a desire.

Second, none of these countries really bought into the strategic stability concept either in terms of doctrine (no-first use), weapons (both qualitative and quantitative) and deployment (de-alerted status).

Finally, there was a belated and limited effort to incorporate these countries into the nuclear order, which meant that they had to fend for themselves. Also, unlike the East-West context, where the US buttressed bilateral arrangements with plurilateral ones, in Asia, Washington confined itself to bilateral arrangements.

The Three ‘No’s’:

Today Asia in general and South Asia (China, India and Pakistan) in particular is characterized by three ‘no’s’ which have a direct impact on the traditional concept of nuclear strategic balance and stability:

First, no no nuclear buildup policy. Instead, Asia is witnessing qualitative and quantitative enhancement in nuclear weapons and delivery systems. In contrast to European nuclear weapon states the South Asian countries are developing a nuclear triad. Part of this is on account of low base.

Second, no arms control experience and reluctance to engage in this endeavour.

Third, no bilateral, regional or global architecture to manage relations and preserve a no nuclear war scenario. Although India and Pakistan have some elements of a bilateral architecture, it is still not fully implemented.

Way Forward:

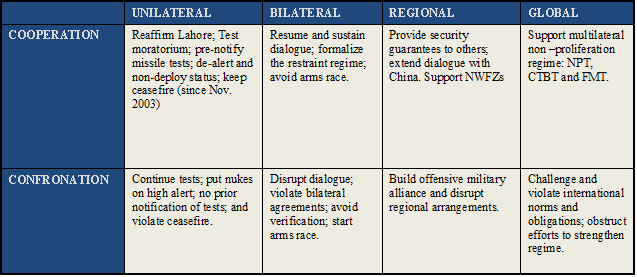

South Asia (China, India and Pakistan) have at least two possible ways forward: cooperation or confrontation. If its follows the latter then the experience will be more like the East-West scenario of nuclear build-up. If it follows the former then it might be more like the European experience.

However, in reality South Asia is likely to see a muddling through approach, with a series of ad-hoc and informal arrangement which are more de-facto than de-jure. In this transformation the US will play a crucial role and should also be considered an Asian power.

The central question for us to consider is: can the de-facto arrangements work in the long term or will they have to be converted into some form of de-jure arrangement? If so, where and how will this de-jure arrangement be established? What role will European powers play in this process?

This talk was delivered at the Contemporary Grand Strategy Colloquium on 10 April 2014.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).