While many government leaders continue to declare their commitment to respect the rule of law as the foundation for peace and human rights, in practice their performance is perforated with lackluster results or outright failure. As a result, people are losing faith in democratic politics and turning to authoritarian alternatives, or simply tuning out. Now more than ever, strong guardrails such as independent judiciaries, robust civil society, and trustworthy elections are needed to stop the slide and build fairer and more accountable systems.

The rule of law recession continues

Unfortunately, study after study confirms that countries are still very far from their own stated allegiance to democracy, rights, and the rule of law. The latest such report, the World Justice Project’s annual Rule of Law Index, shows a continued downturn in respect for the rule of law at the national level. The index, which this year relied on original data collected from 3,400 in-country experts and practitioners and more than 149,000 households, now covers 142 countries representing 95% of the world’s population.

Scores for the rule of law this year fell in 59% of countries surveyed, the sixth consecutive year in which the majority of countries declined. Since 2016, the rule of law has fallen in 78% of countries studied.

Trends and drivers

The main drivers of this worrisome pattern are a growing disrespect for human rights, weakening checks on government power, and malfunctioning justice systems. For example, authoritarian trends marked by centralization of executive power — at the expense of legislatures, judiciaries, civil society, and the media — worsened in 56% of countries this year, somewhat less than in the previous two years but still widespread.

Since 2016, civic participation has dropped in 83% of countries, more than any other indicator, followed by freedom of assembly and association (81%), freedom of opinion and expression (78%), and freedom of religion (76%); these are all core rights enshrined not only in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights but also in treaty law and most constitutions. The ability of civil and criminal justice systems to resolve disputes declined in more states this year (66%), due to greater justice delays and weaker enforcement of judgments.

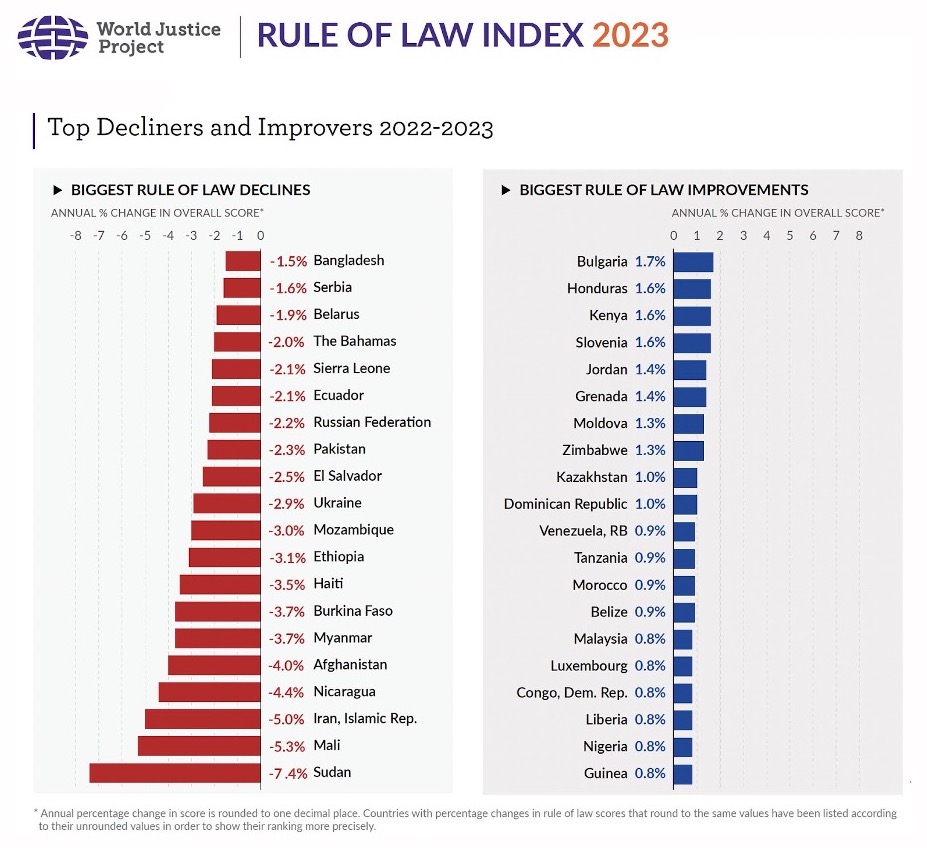

Within these general trends lies a more troubling story: Countries with weaker rule of law have experienced larger declines in their scores than countries with stronger rule of law. Moreover, “improvers” of any type have improved only modestly, while “decliners” have declined more dramatically (see accompanying chart below).

And countries that have declined for five consecutive years (16 of 113, led by Nicaragua, Iran, Myanmar, and Belarus, among the index’s worst performers) far outnumber those that have improved every year for the same period (two: Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan). These trends suggest that rule of law malfunctions can become ingrained, exacerbating efforts to reverse course without long-term political will and resources.

Failure to deliver

As governments fail to deliver basic public services like access to justice, or worse, abuse their citizens’ rights, positive views of democratic institutions and politics drop further. Bad governance and corruption become entrenched, compounding crises and stoking further conflict and displacement within and across borders.

For example, countries high on the international security agenda for years — Afghanistan, Sudan, and Myanmar — are also some of the worst rule of law performers. In this hemisphere, Haiti (ranked 139 of 142) is collapsing before our eyes as governments struggle for months to devise an adequate response, while Venezuela (ranked last) continues to generate a record number of displaced people fleeing persecution and gross economic mismanagement.

Russia offers another telling example of the correlation between authoritarian governance and conflict. Ranking 113 out of 142 countries, and near the bottom in its regional and income group, Russia scored particularly low on such indicators as fundamental rights, criminal justice, and constraints on government power.

Meanwhile, democratizing Ukraine, whose rule of law score had been improving before Russia invaded it, performed significantly better than Russia on those same three indicators.

This year’s disappointing report card on progress toward achieving the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, which includes Goal 16’s promise to “provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions,” provides further evidence of how far national governments still have to go to deliver adequate public goods to their citizens.

Back to basics

It doesn’t have to be this way. Evidence shows that strong liberal democracies with robust rule-of-law regimes provide better domestic and international peace and security. They generally do not go to war against each other and manage internal dissent through nonviolent channels and respect for human rights. Hybrid authoritarian and weak states, on the other hand, are more likely to experience intra- and interstate conflict, generate refugees, hinder women’s equality, and harbor violent extremists.

President Joe Biden’s timely agenda to support democracy at home and abroad, and a renewed programmatic focus by the Department of Justice and the U.S. Agency for International Development on people-centered justice, are encouraging but faces daunting headwinds in the wake of domestic and geopolitical conflicts of a new magnitude. Multiple criminal indictments and ongoing election denialism by a former president and leading contender to return to the White House will continue to test the United States’ ability to reverse its declining rule of law performance and lead by example.

From such storms must come a renewed social and political contract for peace and human dignity. It should begin with a return to the promise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, whose first article declares that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” If states were to uphold this dictum in practice, they would give their citizens a fair voice in how they are governed. They would ensure equal protection of the law, regardless of status or power. And they would create governing systems based on the rule of law, the best guarantor of human rights.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The compounding rule of law crisis

November 10, 2023