Brief overview of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance

On March 1, 2015 Taiwan marked the 20th anniversary of its government-run single-payer National Health Insurance (NHI), a universal health coverage scheme that provides comprehensive health insurance to Taiwan’s 23.4 million citizens and foreign residents. Insurance benefits include outpatient visits, inpatient care, dental care, traditional Chinese medicine, renal dialysis, and prescription drugs. The NHI affords equity and augments social solidarity by providing subsidies for premiums and certain medical services to the poor and disadvantaged populations—those living in remote mountainous areas and offshore islands, and the seriously ill—and a national uniform benefit package so everyone—rich or poor—has the same access to services and receives the same care.[1] There are no financial barriers to needed medical care, and no ambiguity as to who receives what benefits as seen in the complex web of health insurance exchanges under the U.S. Affordable Care Act (ACA) where people with different policies have different benefits, including federally mandated benefits such as birth control for women.[2]

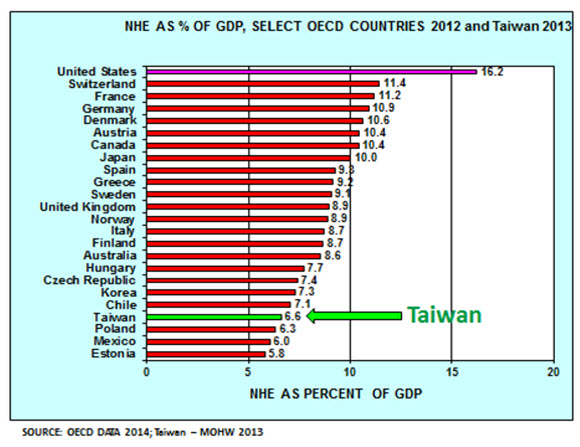

Total health spending in Taiwan in 2013 was 6.63 percent of Taiwan’s GDP, of which the NHI accounted for 52.2 percent. Out-of-pocket spending by the insured accounted for another 35.8 percent, government public health and general administration expenditures 6 percent, and health care investments 5.4 percent.[3] This is low compared to OECD countries where the average health spending was 9.3 percent of GDP in 2012 (Figure 1). Pubic satisfaction with the NHI has been high, averaging in the 80 percent range in recent years.[4] Waiting lines for visits and procedures, if any, are short, and patients have free choice of providers, as there is no gate-keeper system such as that in the UK’s National Health Service or in American HMOs.

Figure 1

Except for the first three years since implementation (1995-1998), annual growth in expenditures in Taiwan’s NHI had typically outstripped revenues. In the period 1996-2008, for example, NHI revenues increased at an annual rate of 4.43 percent while expenditures increased at an annual rate of 5.33 percent.[5] A major health care reform—the Second-Generation NHI (G2-NHI)—implemented in January 2013 reversed the NHI’s financial difficulties. Prior to the G2-NHI reform, the NHI’s revenue was derived primarily from payroll-based premiums. But payroll represented just 60 percent of total national income in Taiwan. The G2-NHI reform established a supplemental premium base. Supplemental premiums now are levied on six additional sources of non-regular-payroll income, namely, bonuses, rent, interest, dividends, professional fees, and pay from second jobs. With the additional supplemental premiums, the total premium base now covers 90 percent of Taiwan’s total national income. The reform has enabled the NHI to not only cover its annual health care expenditures, but also to eliminate accumulated deficits from prior years. In fact, the NHI now has a sizable surplus, something it had not seen since 1998. The NHI’s sound financial status is expected to last through at least 2017.

NHI’s high performance explained

Taiwan’s NHI may be said to be a high performing health care system compared with many other health care systems around the world. In terms of cost-effectiveness, Taiwan’s system outperforms the U.S. system, which spends more than 17 percent of U.S. GDP but, before the ACA was passed in 2010, left some 50 million, or 16 percent of Americans uninsured. The ACA is expected to cover an estimated 30 million Americans by 2020—a goal that may or may not be reached. Even if it is, an estimated 20 million Americans may still remain uninsured at that time.

A main reason for NHI’s high performance is the ability of the government, as the single payer, to set and regulate fees, and impose a global budget system that caps total NHI expenditure. For 2015, for example, NHI expenditure is budgeted to increase 3 percent from its 2014 levels. The NHI Administration (NHIA), the government agency that administers the NHI under the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW), wields near monopsonistic power as the single buyer of and payer for health care services including drugs vis a vis health care providers. This power enables the NHIA to control costs and provide Taiwan’s public with affordable health care services, in sharp contrast to the United States where private health insurers often have limited power to set fees, especially in markets dominated by large provider organizations.

Another critically important factor is the NHIA’s powerful information technology (IT)-driven administrative system, which provides high administrative efficiency at low cost. In 2014 the administrative budget for the NHI was 1.07 percent of total NHI expenditure. This high “medical loss-ratio,” as we would call it in the United States, means more money is available to provide medical services instead of paying for administrative and marketing costs, and earning profits. The NHI’s IT system also provides near real-time information on expenditures, utilization, and public health emergencies like outbreaks of influenza and avian flu.

Challenges going forward

Its many successes notwithstanding, Taiwan’s NHI, like any other health care system around the world, has its share of challenges. The rest of this paper will focus on some of the major challenges. Where possible, comparisons with OECD countries will be drawn to put Taiwan’s health care system in international context.

Population aging

Taiwan has a relatively young population compared to OECD countries except Mexico. While among OECD countries 16.5 percent of the population was 65 years and over in 2013, in Taiwan the comparable figure was 11.5 percent.[6] Taiwan, however, faces an unusually rapid demographic transition—its people are living longer, but fewer children are being born. Taiwan’s fertility rate in 2011 was lower than any OECD country.[7] The rate of aging of Taiwan’s population is therefore accelerating. In 2015, people aged 65 and over will account for 12.5 percent of the population, by 2030 it will be 24.1 percent, and by 2050 36.9 percent.[8]

Aging is a major driver of an increasing prevalence of non-communicable-disease (NCD).[9] Cost of medical care for the elderly will therefore become more of a concern as aging accelerates. Already, in 2011, health care costs for Taiwan’s elderly population accounted for 34 percent of NHI’s total expenditure.[10]

The rising non-communicable-disease burden

NCDs accounted for 79.3 percent of all deaths in Taiwan, 64.2 percent of all deaths among the top 10 causes, and 69.1 percent of all deaths among those 65 years old and over in 2013.[11] Cancer, the leading cause of death in Taiwan since 1982, accounted for 29 percent of all deaths in 2013, followed by cardiovascular disease at 11.5 percent, cerebral vascular disease at 7.3 percent, and diabetes at 6.1 percent.[12] Three major NCDs—cancer, cardio- and cerebral-vascular disease—accounted for 45.9 percent of all deaths among people 65 years and over in 2013.[13]

According to the 2007 Taiwan Survey on Hypertension, Hyperglycemia, and Hyperlipidemia (TwSHHH) conducted by the Health Promotion Administration of the MOHW, almost 40 percent of Taiwan’s citizens aged 20 and over suffered from hypertension, hyperglycemia, or hyperlipidemia.[14] For Taiwan’s elderly, the rates of NCDs are far higher. According to a 2008 government survey, of the elderly population in Taiwan, 51 percent suffered from at least three NCDs, with hypertension being the most prevalent; 70 percent suffered from two or more NCDs, and 90 percent at least one NCD.[15]

The rising burden of NCDs in Taiwan has serious implications for the NHI in terms of both growing utilization of services and associated health care costs, and potentially increased demand for a larger health care workforce. All major NCDs have seen significantly increased utilization of NHI services and costs over time. For example, for cancer care in the decade 2003-2013, the number of cancer patients seeking outpatient care increased by 74.4 percent for the period, outpatient visits increased by 68.7 percent, and the average cost for outpatient visits per cancer patient by 89 percent. For cancer inpatient care, the number of patients increased by 63.6 percent, inpatient episodes by 58.2 percent, and the cost of care per inpatient episode by 1.7 percent.[16]

Is NHI too nice?

To ensure access to medical care for those with the greatest medical need, the NHIA issues a “catastrophic illness certificate,” which exempts all copayments and coinsurance, to patients with one or more of 30 catastrophic diseases, residents of remote mountainous areas and offshore islands, pregnant women and child delivery, children under three, veterans and their dependents, and low-income households. Chronic renal failure and cancer had the highest outpatient costs in 2013, accounting for 45 percent and 33.5 percent of NHI’s total annual outpatient care expenditures, respectively.[17] For inpatient care, cancer accounted for 45 percent of NHI’s total 2013 expenditures, long-term artificial ventilation for 22 percent, and chronic nervous system disease for 11.5 percent, respectively.[18]

As of 2011, 861,000 residents, or 3.7 percent of Taiwan’s population, were holders of the certificate. Medical care costs for this group accounted for 27.2 percent of NHI’s total annual expenditure in 2011,[19] and by 2013 increased to 29.4 percent.

While it is important to remove financial barriers to needed medical care, in the longer term the question of sustainability of the current generous copayment exemption policy must be raised. Going forward, eligibility for copayment exemption should be reviewed through means-testing to prevent reverse income redistribution from the middle class to the rich. At present, all NHI enrollees, regardless of their economic status, are entitled to this generous government subsidy. In addition, the questions of clinical- and cost-effectiveness of care and end-of-life care must also be addressed to reduce futile care and waste; for example, indefinite artificial ventilation for life support of patients in a permanent vegetative state.

Quality of care

Using increases in life expectancy as an outcomes measure, the NHI has brought substantial health improvements to Taiwan’s population. As of 2013, life expectancy in Taiwan was 76.69 years for men and 83.25 years for women, while the figures for the United States in 2011 were 76.3 for men and 81.1 for women.[20] A 2010 study showed that the NHI has been associated with a reduction in deaths from amenable causes—deaths avoidable with access to timely and effective health care.[21]

However, the latest data, released in March 2015 by Taiwan’s MOHW, suggest that the overall level of quality of health care in Taiwan (distinct from improvement) as measured by specific quality indicators, still leaves room for improvement in terms of both clinical- and cost-effectiveness.

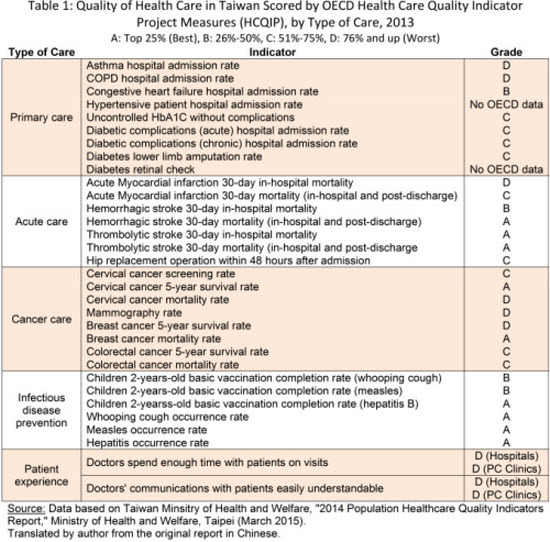

Taiwan’s MOHW has, since 2014, compiled annual reports comparing the quality of health care in Taiwan with OECD countries, using the indicators adopted for the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project (HCQIP). The reports represent, in a forthright and self-critical manner, benchmarks on the quality of health care in Taiwan. Table 1 shows how the Ministry’s 2014 Population Healthcare Quality Indicators Report graded Taiwan’s performance relative to OECD countries, using letter grades A to D where “A” denotes ranking in the top 25 percentile (best), “B” in 26-50 percentile, “C “ in 51-75 percentile, and “D” in lowest 25 percentile (worst). Grading was done for primary care, acute care, cancer care, infectious disease care, and patient experience.

Table 1

Overall, the reported grades indicate that there is significant room for improvement in the quality of care in all areas measured, except infectious disease prevention where Taiwan scored well with four A’s and two B’s out of six indicators. This is not surprising because Taiwan has a long history of outstanding public health service.

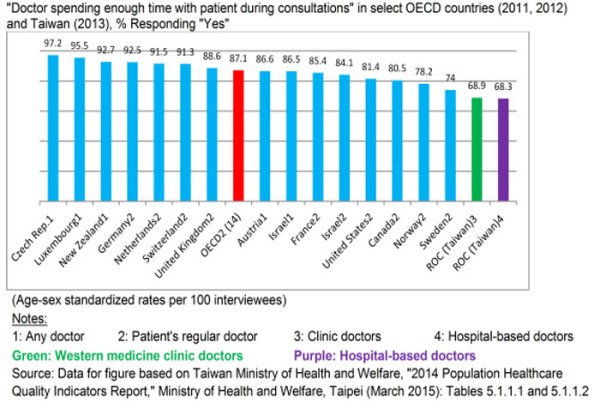

Taiwan’s grades on “patient experience”—D for both indicators—are illuminating. Length of visit time has become an increasingly important measure of patient satisfaction in recent years. Figure 2 shows that Taiwanese are significantly less satisfied with the length of visits to both family doctors and hospital-based specialists than respondents in the 15 OECD countries that collected such data.[22] Large segments of Taiwan’s public view visit lengths to be too short, and differences with some other countries were stark. Although since 2006 the NHIA has implemented “reasonable outpatient visit volume” to discourage high volume and therefore allow for more time per visit, satisfaction on this issue remains low.[23]

Figure 2

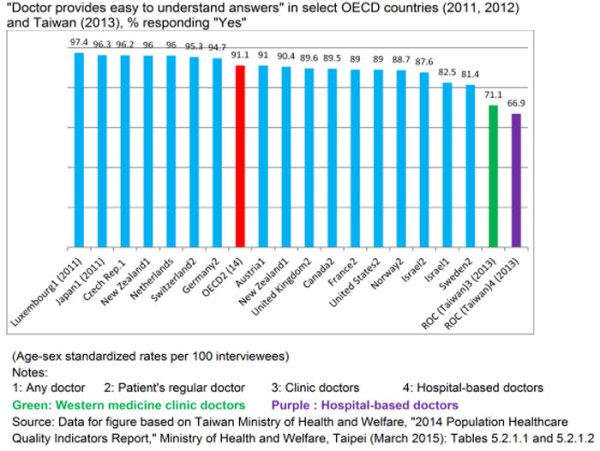

Figure 3 shows that on the indicator “Doctor providing easy-to-understand explanations,” Taiwan also ranked last after the 16 OECD countries in the survey.[24]

Figure 3

The clear message is that doctors in Taiwan need to spend significantly more time and communicate more effectively with their patients on visits.

The D grades on “patient experience” notwithstanding, the NHI continues to enjoy high public satisfaction for the financial protection, comprehensive benefits, easy accessibility, free choice of providers, and virtually no waiting times it offers Taiwan’s public.[25]

Doctor shortages

Compared to OECD countries, Taiwan has fewer doctors and nurses. Physician- and nurse-population ratios in Taiwan are 1.7 doctors and 5.7 nurses per 1,000 population, compared to the median of 3.3 doctors and 8.6 nurses in OECD countries.[26] Taiwan’s low ratios would be considered inadequate by OECD standards, especially in view of the high utilization of health care services in Taiwan—in the decade 2003-2013 overall outpatient visits increased by 20 percent and inpatient episodes by 17.6 percent.[27]

For several years now there have been growing concerns in Taiwan over doctor shortages in certain specialties, namely internal medicine, surgery, pediatric, obstetrics and gynecology, and emergency medicine. The growing demand for medical services driven by both public expectations and a rapidly aging population, the threat of malpractice suits, perceived asymmetry of NHI fees relative to the doctors’ training and productivity, and long work hours are the main reasons some doctors in these specialties have left for “easier” specialties such as dermatology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and cosmetic surgery, where work hours are shorter and more predictable, threats of malpractice suits lower, profits higher, and the working environment more pleasant.

Other factors help explain the doctor shortage in the aforementioned specialties. Since 2000, Taiwan’s low fertility has drastically reduced the demand for OBG and pediatric services, leading to fewer medical graduates choosing those specialties while a growing number of current OBG doctors are reaching retirement age. Growing medical tourism and demand for health care services in some Asian countries, for example Singapore and China, may be drawing some doctors away from Taiwan by attractive offers of higher salaries and shorter work hours. Emergency room crowding may be at least in part due to misuse by patients. For example, patients are known to go to emergency rooms (especially ER at medical centers) for minor problems such as week-old bruises, bleeding acne, mosquito bites, or water in the ear from swimming.[28] Last but not least, it is easy for doctors to switch specialties in Taiwan.

Proposed remedies to address doctor shortages include training more doctors than the current government quota of 1,300 medical graduates a year, and reducing waste from overuse of medical services by patients. Both measures, however, are easier said than done. Some policy makers and experts, as well as professional associations in Taiwan, including nurses associations, are opposed to increasing the number of new entrants into their professions.[29]

According to a December 2014 report released by Taiwan’s National Institute of Health, the research arm of the MOHW, Taiwan could face a serious shortage of up to 7,000 doctors across five specialties by 2022: 3,099-3,788 in internal medicine, 1,044-1,519 in surgery, 46-216 in obstetrics and gynecology, 44-361 in pediatric medicine, and 723-795 in emergency medicine.[30] Taiwan needs a thorough review of its health workforce policy to meet changing demographic needs.

Nurse shortages

A strong argument can be made for increasing nurse staffing levels to improve the quality of care and patient safety in Taiwan. According to research funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, among other studies, low nurse staffing levels tend to have “higher rates of poor patient outcomes such as pneumonia, shock, cardiac arrest, and urinary tract infections.”[31] Pneumonia is the fifth leading cause of death in Taiwan. Might this be related to the low nurse-bed ratios in Taiwan’s hospitals? Families of patients in Taiwan often fill the void left by sub-standard staffing levels of nurses in Taiwan’s hospitals. This is not just a burden to families; perhaps more significantly, it also poses a threat, sometimes serious, to patient safety as families are not trained professionals and cannot replace the work of trained professionals. Adequate nurse-bed staffing may be another important area to address to help reduce amenable mortality in Taiwan. Quality improvement may be the most important area to focus on in Taiwan’s next stage of health care reform to create greater efficiency in NHI.

Long term care

Taiwan currently does not have adequate long term care (LTC) facilities and personnel, but these are urgently needed. Taiwan’s government has been planning for improved LTC and will implement a program once it figures out how to finance and organize it, including an adequate LTC workforce.

Payment reform

Fee-for-service (FFS) has been the predominant method of provider payment in Taiwan. Financial incentives inherent in an FFS payment system help drive supply-induced demand, which may partially explain the high utilization of health care in Taiwan. As of 2014, the average number of visits to doctors per person per year (excluding dental and traditional Chinese medicine visits) was 11.05-12.07.[32] These rates are lower than Japan’s 13.0 visits and South Korea’s 14.3 visits per capita per year,[33] but roughly twice as high as the median of 6.6 in other OECD countries.[34]

At the same time, the easy-access that health insurance such as the NHI facilitates creates the well-known moral hazard inherent in all health insurance schemes. Coupled with the cultural belief by many in Taiwan that more health care is better, the demand side drives up the utilization of health care. On the supply side, competition for patients among providers in Taiwan, who are predominantly private, creates a supplied-side induced demand for health care under Taiwan’s predominantly FFS payment system. Supply-induced demand (known as SID) plagues many health-care systems around the world.

Nations look to payment reform to make their health care system more efficient. Taiwan is pursuing alternative ways to pay providers, including diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospitals, pay-for-performance, bundled payments, and capitation to reduce waste and low value care. Payment reform, however, is one of the most challenging tasks in health reform anywhere, the United States included. In most countries FFS is still the predominant payment method and the one most favored by providers. For example, in the U.S., despite repeated calls for moving to “value-based reimbursement” for “better value in health care” by insurers, health policy makers, and analysts, FFS is still the predominant method to pay providers.

Taiwan’s NHIA is expanding the use of DRG payment for hospitals, experimenting with pay-for-performance, case payments, and capitation. In this regard countries have much to learn from one another.

Conclusion

Taiwan’s NHI has been successful in providing generous and equitable universal health coverage for Taiwan’s 23.4 million citizens and residents, especially in view of the relatively limited resources—only 6.6 percent of Taiwan’s GDP in 2014—made available to it. A strong case for higher health spending, however, can be made for several reasons.

First, higher health spending would allow faster adoption of new medical technology such as new cancer therapies. New technology, including drugs, is often introduced two years after their introduction in the United States, and sometimes up to five years later.[35] In 2009, the NHI covered only 13 of the total of 17 target therapy drugs for cancer then available on the world market.[36] Along with waiting for better cost-effectiveness data, budgetary constraints contribute to delays in adopting new technologies. Larger budgets therefore would allow speedier adoption of new technologies.

Second, higher health spending would allow upward adjustment of some fees to cover costs. Currently, profit margins on some services are negative.

Third, staffing ratios of doctors, nurses, and allied health care workforce may be increased to improve the quality of care and patient safety. Other reasons for higher health care spending include developing health technology assessment capabilities including evidence-based clinical guidelines and pathways to improve NHI’s clinical- and cost-effectiveness and patient safety, implementing long term care, and conducting health services research, such as innovative payment methods pilots and delivery models.

Taiwan’s public must also play a role in sustaining its cherished NHI, considered by many as the keeper of social peace, by not overusing and abusing the system while also refusing to pay higher premiums, the combination of which is the perfect recipe for the creation of the Tragedy of the Commons in which rational individual choices work to the detriment of the larger group. Taiwan’s public must be willing to pay a little more for better quality health care. With per capita GDP (international dollars) in 2014 at 45,854, Taiwan is as rich as Germany (45,888), Canada (44,843), and Denmark (44,343)—all of which spend far more on health care—and has the fiscal capability to spend more on health care.[37] It is a matter of willingness to pay and not ability to pay. The two are not the same. A country may be willing to pay more for health care in principle, but it just does not have the resources to do that (ability to pay). This is the case in many developing countries. On the other hand, a country may have ample ability to pay, but may not wish to allocate more resources to health care (willingness to pay). Taiwan has been in the second category. It should be understood that any additional funding for the NHI be earmarked for targeted benefits to avoid waste and misuse, as this author has argued as early as 2003.[38]

Finally, Taiwan’s providers must also be willing to be held more openly accountable for the quality of the services they deliver.

Taiwan has shown the world how a single-payer health care system can control costs while providing generous universal health coverage. Recent published reports comparing the quality of health care in Taiwan with OECD countries, however, show that Taiwan’s policy makers recognize the need to improve the quality of its health care in almost all areas of clinical care measured in the OECD HCQIP.

Quality improvement represents an opportunity for the NHI to further improve its efficiency. One of Taiwan’s strengths is its willingness to learn from other countries, and this extends to health policy makers – in contrast to U.S. health policy makers who show much greater reluctance to learn from systems abroad. The very creation of Taiwan’s NHI, which is basically an amalgam of the Canadian health insurance system and the German method of financing health care, is such a manifestation. Another is the introduction of global budgets to control health care cost and eliminate deficits, which also was inspired by earlier German reform policies. The fact that Taiwan health policy makers benchmark the OECD shows that Taiwan is still looking abroad for lessons. In the case of quality of care, one can expect quality improvement to be a major part of Taiwan’s next health reform.

[1] For a more detailed discussion of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance, see Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance,” Health Affairs 34, No. 3 (2015): 502-510.

[2] See, for example Radnofsky, Louise, “Insurers faulted over women’s health care,” Wall Street Journal, April 30, 2015.

[3] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Statistics and Trends in Health and Welfare 2013,” Taipei (2013). Chinese.

[4] Taiwan National Health Insurance Administration, “2014-2015 National Health Insurance Annual Report,” by Huang San Gui, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taipei: (December 2014).

[5] Chih-Liang Yaung, “Looking After the Disadvantaged, Focus the Economy to Benefit the People: Proposal for NHI Premium Rate Adjustment According to the Law,” (Oral Report to President Ma Ying-Jeou. Taipei, March 17, 2010) Chinese.

[6] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Statistics and Trends in Health and Welfare 2013,” Taipei (2013): 131. Chinese.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Taiwan National Development Council, “Republic of China Population Estimates 2014-2061,” Taipei (2013) Chinese.

[9] Prince, Martin J., Fan Wu, Yanfei Guo, Luiz M. Gutirerrez Robledo,Martin O’Donnell, Richard Sullivan, and Salim Yusuf. “The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice,” Lancet 385, Issue 9967 (2015): 549-562.

[10] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Second-Generation National Health Insurance Comprehensive Evaluation Report,” Second-Generation National Health Insurance Evaluation Commission. Taipei (2014): Chinese.

[11] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “2013 Statistical Analysis of Causes of Deaths in Taiwan,” (News conference, June 25, 2014). Chinese.

[12] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare. “Statistics and Trends in Health and Welfare 2013,” Taipei (2013): 9. Chinese.

[13] Ibid., 13

[14] Health Promotion Administration, “2014 Health Promotion Administration Annual Report: Promoting Your Health.” Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taiwan (2014): 85.

[15] Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Taiwan Province of China’s Experience with Universal Health Care Coverage,” in The Economics of Public Health Care Reform in Advanced and Emerging Economies, eds. Benedict Clements, David Coady, and Sanjeev Gupta. (Washington DC: International Monetary Fund, 2012), 253-279.

[16] Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Taiwan. Statistics and Trends in Health and Welfare 2013”. Taipei (2013): 85. Chinese.

[17] Ibid., 93

[18] Ibid. Data calculated by author by averaging costs for male and female patients.

[19] Taiwan National Health Insurance Administration, “NHI 2012-2013 Annual Report,” Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taipei: Taiwan (2012).

[20] Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance,” Health Affairs 34, No. 3 (2015): 507.

[21] Ibid., 507

[22] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Population Healthcare Quality Indicators Report,” Taipei (2014).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., 88.

[25] Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance,” Health Affairs 34, No. 3 (2015): 502-510.

[26] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Statistics and Trends in Health and Welfare 2013,” Taipei (2013): 135. Chinese.

[27] Ibid., 55

[28] Huang Wen-Yen, “Visiting Hospital Emergency Rooms Because of Subdural Hematoma: Bad Habits of Treating Minor ailments for Major Illness,” United Daily News. April 7, 2015.

[29] Author’s personal meeting with Huang Huang-Hsiung, Member of the Control Yuan, Government of Taiwan, in Taipei, Taiwan, September 6, 2012. Huang is author, with Sheng Mei-Chen and Liu Hsing-Shan, of a major report, “Comprehensive Physical of the National Health Insurance,” (Taipei: Taipei Medical University Wu-Nan Publishing Company, January 2012). Chinese.

[30] Li-Ting Chen, “Doctor shortages/Medical care facing shortages of 7,000 doctors in five specialties by 2022” United Evening News. Taipei, Taiwan, December 19, 2014.

[31] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Hospital Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care, by Mark W. Stanton. Research in Action Issue 14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, Maryland, (March 2004): http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/services/nursestaffing/nursestaff.pdf

[32] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Second-Generation National Health Insurance Comprehensive Evaluation Report,” Second-Generation National Health Insurance Evaluation Commission. Taipei (2014). Chinese.

[33] “OECD health statistics 2014,” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Updated November 2014; accessed January 28, 2015, http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx

[34] Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, “Statistics and Trends in Health and Welfare 2013,” Taipei (2013). Chinese.

[35] Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Lessons from Taiwan’s Universal National Health Insurance: A Conversation with Taiwan’s Health Minister Ching-Chuan Yeh,” Health Affairs 28, no. 4 (2009): 1035-1044; and, Yaung, Chih-Liang, “Transparency in Drug Policy Meetings are Helpful to the NHI,” United Daily News, April 14, 2015. Chinese.

[36] Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Lessons from Taiwan’s Universal National Health Insurance: A Conversation with Taiwan’s Health Minister Ching-Chuan Yeh,” Health Affairs 28, no. 4 (July/August 2009): 1037.

[37] Per capita GDP data based on International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook Database, Updated April 2015, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/index.aspx

[38] Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Taiwan’s New National Health Insurance Program: Genesis and Experience So Far,” Health Affairs 22, no. 3 (2003): 61-76.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edTaiwan’s health care system: The next 20 years

May 14, 2015