This piece is part of the Taiwan-U.S. Quarterly Analysis series, which features the original writings of experts with the goal of providing a range of perspectives on developments relating to Taiwan.

India’s interest in and interactions with Taiwan have grown steadily since the end of the Cold War, as economics and politics have combined to increase Taiwan’s significance to India.

Taiwan has consistently provided a window into the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for India. This dynamic builds on the legacy of India’s relationship with the Kuomintang that were forged during then President of the Republic of China Chiang Kai-shek’s 1942 visit to India, when he insisted on meeting with Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, despite U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s objections. When the Kuomintang retreated from the mainland to Taiwan, these ties were subsequently carried over.

While India was one of the first non-communist states to recognize the PRC, unofficial ties with Taiwan continued through the 1950s and 1960s. India’s “Look East” policy from 1992 increased Taiwan’s salience in Indian policy, and the relationship gained substantive economic and other content. In 1993, the two sides agreed to establish representation in each other’s capitals, namely the India-Taipei Association for India in Taipei and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center in New Delhi and Chennai, India.

Since then, the relationship has grown in depth and breadth, as India opened up and began to integrate its economy with the world after initiating economic liberalization in 1991. This has occurred under Indian governments of different ideological persuasions, suggesting that there is strong consensus on both sides.

While foreign direct investment from Taiwan into India grew slowly initially — $805 million cumulatively from April 2000 to 2019 — recent years have seen several major commitments, such as the Taiwanese multinational Foxconn’s planned investment in semiconductors and consumer electronics in Maharashtra, and possibly in electric vehicles. A bilateral investment promotion agreement is now in place. Trade has also grown rapidly recently. More significant for India than the quantity is the quality of the trade and economic exchanges in terms of semiconductors and high technology. Arrangements are now in place for the avoidance of double taxation, and shipping and airline and other connectivity is steadily improving.

Cooperation in science and technology has grown with over 80 joint projects carried out before the pandemic, and almost 3,000 Indians now study in Taiwan. Economic and other relations are covered by bilateral investment, avoidance of double taxation, and customs cooperation agreements and arrangements.

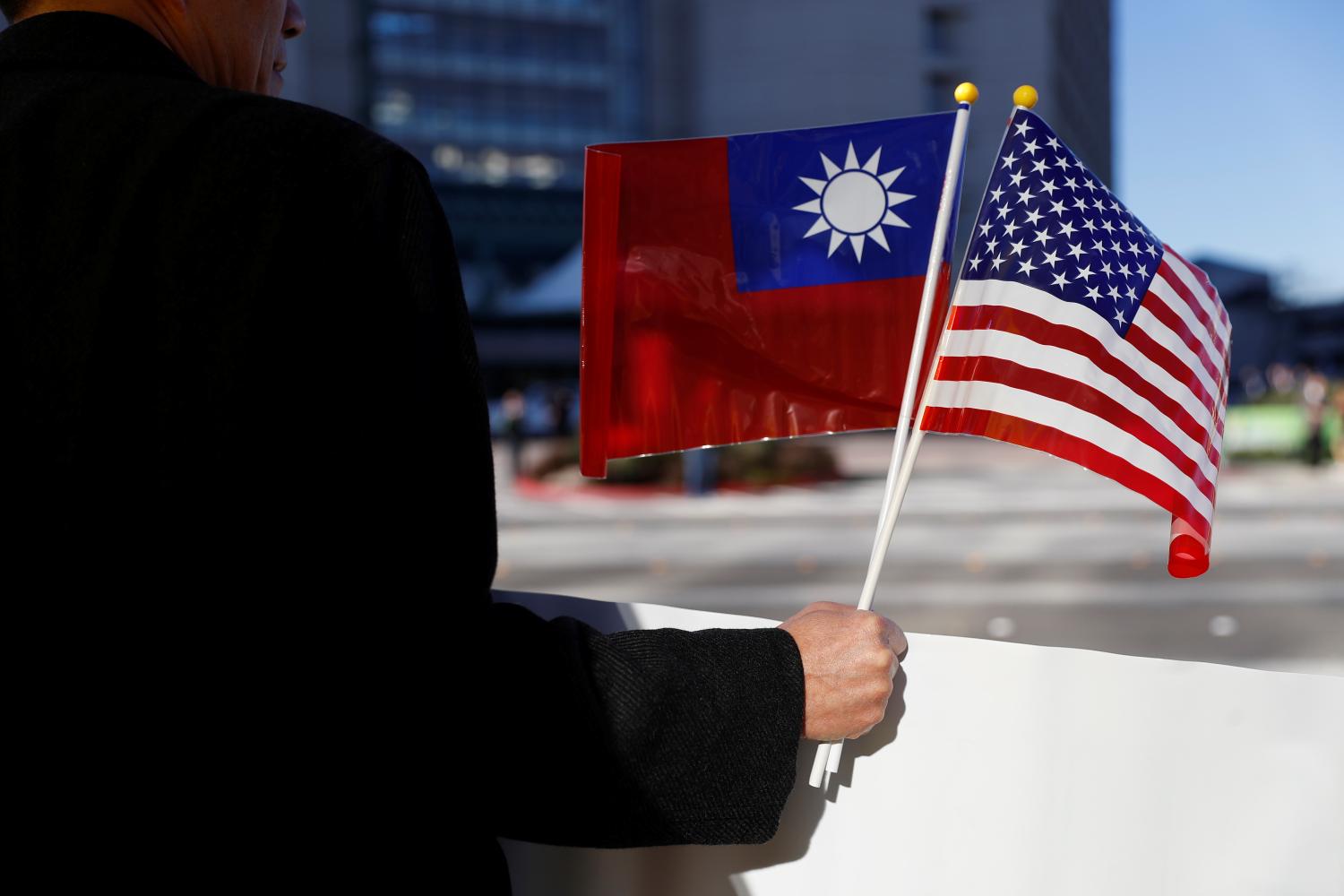

There is a broader Indian interest in peace and security throughout the Indo-Pacific and in maritime Asia, of which Taiwan is a significant part. As early as the Formosa crisis of 1958, where India acted as an intermediary between the PRC and the United States while the PRC shelled islands in the Taiwan Strait, India has made it clear that it hopes and works for a peaceful resolution of the issues between the PRC and Taiwan. More recently, as India-China relations have deteriorated, and the situation in China’s near seas and around Taiwan has become more strained, officials in India have spoken out. Responding to rising tensions in the wake of U.S. Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, India’s Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson expressed concern on August 12, 2022 at these developments and urged restraint and the avoidance of unilateral actions which might alter the status quo. Instead, he urged a de-escalation of tensions and efforts to maintain peace and stability.

Today, nearly 55% of India’s trade with the Indo-Pacific region passes through the South China Sea, and a large portion of that goes through the Taiwan Strait. With rising stakes in the relationship with Taiwan and in regional peace, it is only natural that India should be increasingly concerned about the rising tensions in this extended maritime space and across the Taiwan Strait. India has therefore sought to work with partners who share its concerns and approach, such as the Quad (a grouping comprised of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States) to make the Indo-Pacific free, open, and secure. What form that will actually take in practice will depend on how the situation and Indian capabilities develop in the near term.

For the future, it seems safe to say that India’s interest in peace and the status quo being maintained across the Taiwan Strait will likely grow. India’s “Act East” policy (the present incarnation of “Look East”) and Taiwan’s “New Southbound Policy” are aligned in expressing official determination to carry present processes of diplomacy, trade, economic, academic, and other forms of contact forward, despite the fraught subregional context within which the India-Taiwan relationship operates.

With the worsening of India-China relations in the last decade, there are influential voices in the Indian strategic community calling for a more active Indian political engagement with Taiwan. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs spoke in 2018 of the need to review “India’s deferential foreign policy towards China,” and of India “using all options including its relations with Taiwan” in the event of China being unwilling to reconsider its stance on the border and sovereignty. Since then, the situation on the border has worsened considerably. But the Indian government has been careful to avoid taking steps related to Taiwan which might worsen already difficult ties with a China. This restraint is unlikely to be reciprocated by China on territories that India considers its own, such as Kashmir. It has been several years since the Indian government reiterated its commitment to a “One China” policy, a phrase that seems to mean different things to different people. It might therefore bear watching how Indian thinking on Taiwan evolves in the future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Taiwan: An Indian view

December 16, 2022