Developing countries face an urgent need to invest in projects that allow them to transition to green economies, adapt to climate change, and sustain inclusive growth. To do this, they need a pipeline of high-quality projects and secure and affordable long-term development finance.

Since the 2009 financial crisis and the subsequent period of extraordinary monetary policies, many developing countries accessed private credit and bond markets to supplement (and in several cases replace) domestic savings. Now that monetary policy and capital markets in advanced economies have tightened, the net resource transfers from private sources have reversed. (Net resource transfers are defined as gross disbursements less amortization payments less interest payments and fees.)

In this blog, a snippet from a longer working paper on options to address developing country debt problems, we provide some empirical estimates of the size of the decline in net transfers. We separate China from other developing countries because China is so large it can conceal what is happening elsewhere in the developing world, and because China is itself a large net creditor to many developing countries.

Our focus is on the international financial institutions, because these are the subject of much upcoming debate during the Spring Meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in Washington, D.C. in April, and on private capital flows to sovereign developing country governments, because the volatility in these is a major source of the debt repayment difficulties in which many countries now find themselves.

This is not an exhaustive picture of capital flows to developing countries—remittances, foreign direct investment, bilateral aid and export credits are also important. But none of these other flows feature centrally in answers to the question: Where will large increments in financing for sustainable development investments in developing countries come from? So far, the only pragmatic response has been MDB loans and private capital mobilization.

The big picture on net resource transfers to developing countries in 2023

Our main finding is that there are two separate worlds of development finance—official and private. Official multilateral institutions contribute positively to net transfers, especially through their concessional financing channels where maturities are long and interest rates and fees are low. Net transfers from private sources, however, have been massively negative for the past two years.

A second finding is that almost all the institutions we cover had far lower net resource transfers in 2023 than in 2022. In most cases, this is due to the rise in interest obligations due to rate hikes that started in mid-2022—the exception being for concessional finance, which has a tradition of zero interest rates and fixed fees or charges to cover administrative costs. It is also the case that developing country sovereigns reduced gross financing in 2023. Few countries approached the IMF for new programs. No IDA-eligible country issued a bond in 2023.

Much of this is well-known. The surprise is the size of the numbers.

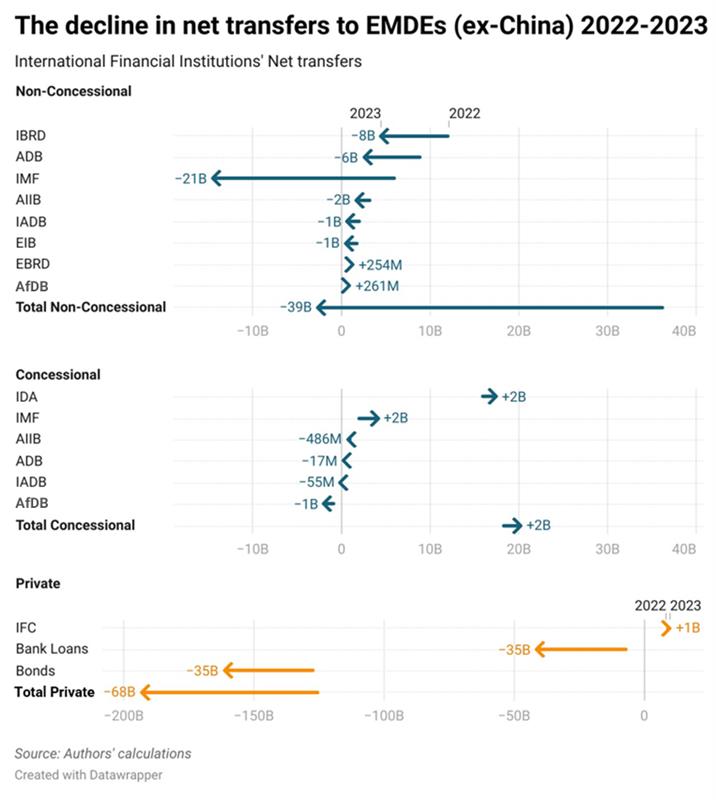

The figure below shows net transfers from select institutions and groups of private creditors for 2022 and 2023, with arrows indicating the change between the two years. Most of the arrows point left, implying lower net transfers in 2023.

The top panel of the figure shows net transfers from the non-concessional windows of select multilateral financial institutions (here, resources from the IMF General Resources Account are treated as non-concessional, while those from the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust are counted as concessional). In 2022, the resource transfers were positive for every institution. In aggregate, they amounted to $36 billion. By 2023, a combination of rising interest rates and reduced access to IMF resources reduced the net transfer figure by $39 billion, to a small negative number; minus $2.7 billion.

The second panel shows the transfers of concessional resources through multilateral agencies. In 2022, these transfers amounted to $18 billion, and they increased to $20 billion in 2023. These transfers are significant for low- and lower-middle income countries. High market interest rates do not affect concessional finance transfers.

The third panel shows lending by private commercial banks and bondholders (and we include public institutions like the International Finance Corporation (IFC) that mobilize private resources for private investments). In 2022, bondholders and commercial banks were already withdrawing $125 billion from developing countries. In 2023, they withdrew even more—$193 billion. Adding these together, private lenders have taken over $300 billion out of developing countries in just two years.

Figure 1.

Sources:

- International Monetary Fund website for all IMF numbers.

- IFC Balance Sheets for all IFC numbers.

- International Debt Statistics for 2022 numbers and private bond and bank loans 2022-2023 numbers.

- IATI for 2023 EBRD, IADB, and ADB numbers.

- World Bank Group Finances for IBRD and IDA 2023 numbers.

- Author’s calculations based on International Debt Statistics and balance sheets for AIIB and EIB 2023 numbers.

Policy implications

The harsh reality of massive private capital disengagement from developing countries provides the backdrop to the Spring Meetings. Developing countries are faced with a predicament. In 2023, they avoided default by sharply constraining fiscal spending, including investments. But this has come at a cost. Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe and Central Asia are barely investing enough to cover the depreciation of their existing capital stock. There is nothing left over for development or growth. This is terrible news for the populations of these countries. It is also bad news for the rest of the world. Without all developing countries investing in the transition to green economies, there is no chance of staying on a trajectory that results in net zero global emissions by 2050. And right now, Asia is the only region where developing countries could potentially reorient investments to put themselves on a sustainable growth path.

There are, therefore, two priorities for the Spring Meetings.

First, stem the outflow of private capital. The recent IMF agreement with Egypt shows how rapidly private capital flows can be reversed when confidence is restored. Of course, accompanying the Egypt deal is a massive $35 billion conversion of debt to equity by UAE investors, the details of which remain murky, but the broad strategy of accompanying macroeconomic reforms with specific investments to jump-start growth is one that other countries could emulate.

The Spring Meetings should bring about a new start to how the IMF relates to developing countries—as a partner with whom to build support and confidence, rather than as an ambulance that is only called when the patient is deathly ill. A good start has been made to raise the IMF’s ability to provide liquidity so that its programs can make a difference to confidence. Cumulative access limits have been raised from 435% to 600% of quota. And there is room to speed up disbursements from the Poverty Reduction Growth Trust and the Resilience and Sustainability Facility: Net disbursements were just SDR2.4 billion and 0.6 billion respectively in 2023. But programs need to be more focused on core macroeconomic rather than structural issues—everything cannot be macro-critical.

The second priority is to align all investors, particularly the multilateral development banks, with the new growth agenda. There is no point (from a development perspective) to MDBs providing large program loans only to see the money leave the country in payments to private creditors. MDBs have to orient their programs to deliver high-quality investments. They have the ability to do this. In our working paper, we have documented the significant returns to World Bank investment projects in all types of countries, providing evidence that it is project identification and preparation rather than country characteristics that is the most important factor for project success. There are now opportunities to do this at scale: to build project pipelines, to support country platforms, to reform sectoral and regulatory policies, to mobilize private finance with new risk-taking instruments. The MDB Heads collectively indicated a few months ago that they were implementing financial reforms to unlock $30-40 billion per year in new lending over ten years; a good start but nowhere near enough for the needed investments in client countries.

This has been said before. What is new is that the World Bank is in the process of revamping its scorecard of development impact. It has a new mission in place: “to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity on a livable planet.” It must now take accountability for helping its clients with sharply scaled-up investments needed to realize this vision. It cannot do this just with its own financing—it is simply too small to have a material impact on its middle-income clients given the size of their GDP. It must bring in private capital in a more systematic way. This is the biggest and most important challenge for the World Bank and management of other MDBs. The Spring Meetings will show whether they truly have new ideas for how to do this.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Swimming against the tide on financing for development

April 11, 2024