The COVID-19 pandemic has had an enduring, negative effect on K-12 student learning, judging by the most recent NAEP results released in January. This was the second set of NAEP results gathered and released in the wake of the pandemic; any latent hopes for a quick recovery were dashed as students continued to slide in reading and showed a tiny rebound in math.

Why aren’t students bouncing back? A plausible explanatory factor is the marked increase in student absenteeism during the pandemic, which has been well documented across multiple contexts. Even more, student absenteeism has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels and has lagged among economically disadvantaged students, roughly aligning with test result patterns. When students are absent from school, they’re missing out on learning, and extra recovery efforts are squandered.

Students, however, may not be the only ones missing school after the pandemic—teachers appear to be absent more, too. Prior research shows that teacher attendance is a key factor associated with student learning and may influence student attendance. In the context of pandemic recovery efforts, teachers and staffing challenges have emerged as key bottlenecks to schools’ successful operations. In this post, we explore teacher absenteeism during and since the COVID-19 pandemic. We have a particular interest in how teacher attendance has changed in schools that serve high shares of disadvantaged students because these areas suffered the brunt of the pandemic-driven declines in learning.

Shifts in teaching during the pandemic

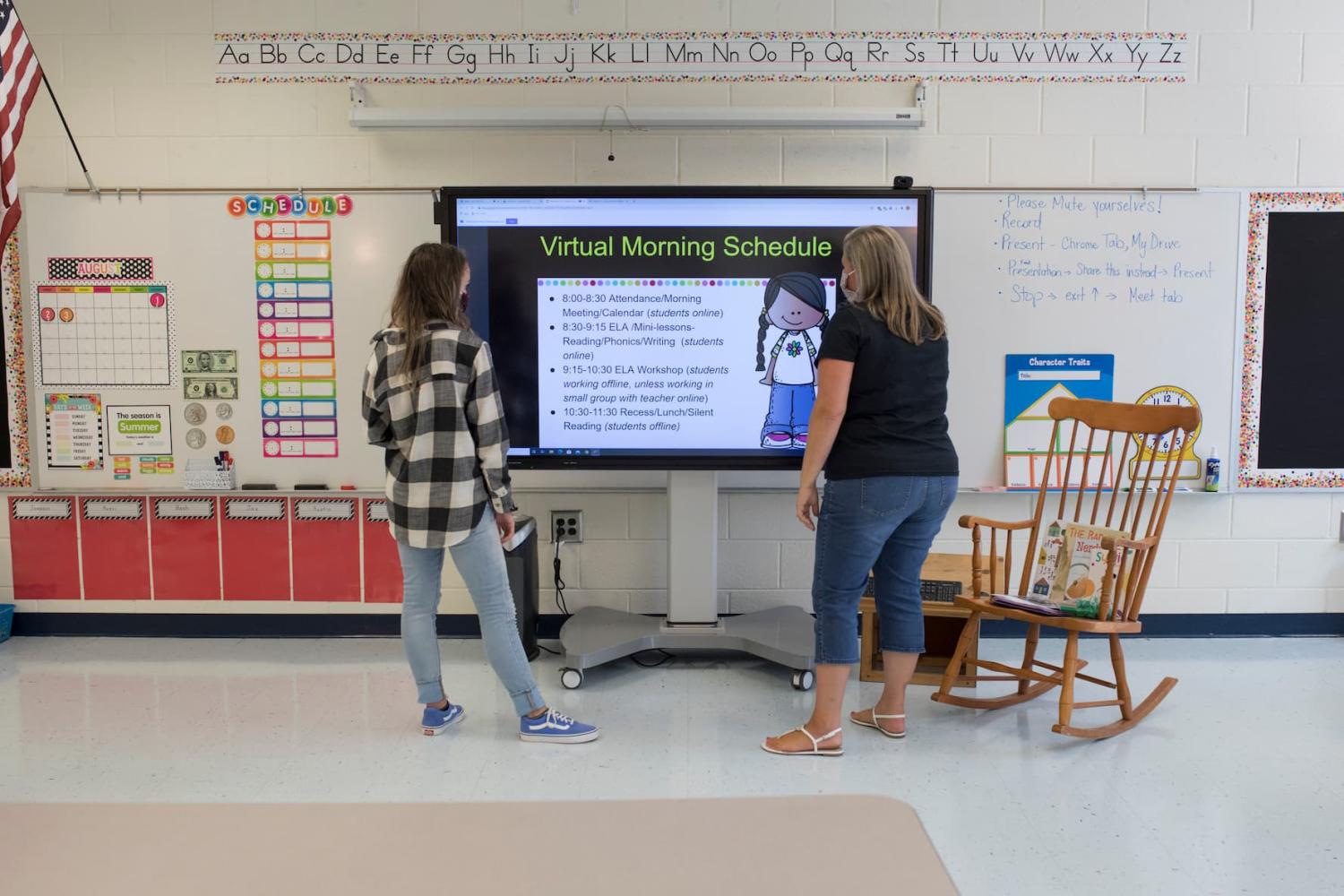

Teachers’ roles have been in flux during this pandemic era. They were front-line responders as virtually all schools quickly transitioned to online instruction during the spring of 2020. Once back in person, teachers had to pivot their instructional models yet again. They had to deal with new parental pressures regarding hot-button issues from COVID-19 reopening plans to discussions about race or gender. They’ve also faced students who are now more distracted by screens and less engaged in learning.

Given how fluid teaching has been during the pandemic, it is not surprising that staffing emerged as a key challenge for many schools. Teachers were expressing widespread dissatisfaction with their jobs and, at least in some states, were turning over at higher rates than in the prior decade or so. The status of the teaching profession sunk to historic lows, and new teacher candidates dwindled in supply. Combined with the pace at which schools were replacing teachers (and hiring for new positions), staffing grew much more difficult, prompting widespread reports of teacher shortages.

Might teacher absence also have been affected over this period? We know from pre-pandemic work that rates of teacher absenteeism were already elevated nationally: Nearly 29% of teachers were considered chronically absent (missing 10 or more days of school) in the 2015-16 school year. Given the challenges that teachers and schools faced during this era, it is reasonable to expect that teacher absences may also be higher in the wake of the pandemic.

Limited information about teacher absenteeism since the pandemic

Yet, hard data on teacher absenteeism during and since the pandemic have been hard to come by. The Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) has been a primary source for teacher absenteeism data on a national scale, though it has not updated this variable since the 2017-18 data collection1.

Meanwhile, some novel types of data have entered the picture. For example, the May 2022 School Pulse Panel collected by the Institute for Education Sciences found 72% of responding schools reported teacher chronic absenteeism increased since the pandemic, based on subjective reports from school administrators. There were media reports of substitute teacher shortages during the pandemic’s heights. And in a June 2024 Bloomberg article , substitute staffing provider Kelly Education said its own data from school systems in 40 states show that as many as 10% of teachers are absent daily, up from 6% before the pandemic.

Our search found just four state or local sources that provide quantitative, administrative data on teacher absence during the pandemic. First, teacher chronic absence rates initially dropped sharply in New York City during the pandemic before surging about 6 percentage points in 2023. Second, a new investigative analysis published in the Oregonian found the share of chronically absent teachers in ten Portland-area districts increased by an average of 11 percentage points since 2019. Also, a 2023 report on the Michigan teacher workforce surveyed district leaders, who reported weekly teacher absences increased by more than 50% between the 2019-20 and 2022-23 school years. And finally, Tim Daly’s blog raised awareness about rising teacher absenteeism in Chicago Public Schools since the pandemic.

Thus, despite the lack of authoritative data, reporting and evidence from a variety of sources point to teacher absenteeism patterns that, like chronic student absenteeism, have surged and remain elevated in the wake of the pandemic. However, specifics about how widespread these patterns are, and whether they disproportionally impact students in high-poverty schools, remain unclear.

New analysis of teacher absenteeism in 4 states

To better understand how the pandemic influenced teacher absenteeism, we collected all data on teacher absenteeism reported at the school or district level that state education agencies have publicly released during the pandemic years. Reporting at the school or district level is critical, as this enables us to explore whether any changes in teacher absenteeism correlate with underlying student disadvantage. We found four states that meet these criteria: Connecticut, Illinois, Nevada, and South Carolina.

We sought to run a parallel analysis across all four states. We used information from the Common Core of Data (CCD) about free or reduced-price lunch eligibility; this is our best proxy for student disadvantage2. We limited the analysis samples to all schools or districts that had non-missing yearly absenteeism measures between 2018-19 through 2022-23 (SC did not report in 2020-21 but reported all other years).3

We should note that each state publicly reports our key outcome in slightly different ways. Connecticut reports the average number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) days that teachers are absent. Illinois reports the chronic absenteeism rate (more than 10 days absent in a school year) among teachers. Nevada reports the percentage of educators who are present to provide instruction to students on an average school day. South Carolina reports the average percentage of teachers present on a school day. We do not have enough information needed to make all states’ measures represent the same unit, though we can make sure they all represent some form of missing school (which we henceforth call teacher absenteeism). Thus, we transformed the average attendance rates reported in South Carolina and Nevada to average absence rates4.

Teacher absenteeism shifted dramatically in 3 of 4 states during the pandemic

We begin the analysis by first plotting the average absenteeism metric in each state over time, along with the means observed in economically disadvantaged (ECD) and non-ECD schools (districts in the case of IL). We classify schools in each state as economically disadvantaged (ECD) based on whether they fell above or below the state’s median free/reduced-price lunch rate during the pre-pandemic period (thus, 50% of schools in all four states are classified as ECD). Because each state outcome is reported slightly differently with different axis scales, we graph these in separate figures.

FIGURE 1

Annual teacher absenteeism from 2018 through 2023

In three states (Connecticut, Illinois, and Nevada) absenteeism dropped in the height of the pandemic (2019-20 and 2020-21 school years) before surging in the post-pandemic years (2021-22 and after). Recall that a similar drop followed by a surge was observed in NYC teachers’ data. The initial declines in absenteeism during the pandemic seem reasonable, considering that nearly two-thirds of students nationwide were attending class online during the fall of the 2020-21 school year. Showing up online to cover instructional duties was presumably easier for many teachers during this era, a conclusion also corroborated by an analysis of a regular teachers’ working conditions survey in Illinois collected over the pandemic.

South Carolina was the only state where teacher absences basically held steady during the pandemic. Though we cannot definitively say why South Carolina differs from the other three states, we suppose instructional modes may have something to do with it. An estimated 68% of students in South Carolina had access to full-time, in-person instruction throughout the 2020-21 school year, which was far higher than estimates of 35% in Connecticut, 10% in Illinois, and 14% in Nevada. This suggests pandemic school closures were more ephemeral in South Carolina and may explain why teacher absenteeism changes were muted.

Moving to the post-pandemic era (2021-22 and beyond), absenteeism measures in all four states exceed their pre-pandemic baselines. A comparison of Nevada and South Carolina is striking. Post-pandemic, Nevada’s mean absenteeism rate more than tripled while South Carolina only inched up by a little over a percentage point (representing less than 20% of the baseline rate).

We should also acknowledge that states or school districts may have changed how they count absenteeism during the pandemic, especially as the shift to remote learning required on-the-fly adaptations to many school operations. However, all four states publicly report these absence figures as though they are consistent over time without any mention of changes to reporting standards.

Clark County School District behind Nevada’s absenteeism surge

The magnitude of Nevada’s post-pandemic surge is quite alarming, which prompted further investigation. The data themselves offered no reason to suspect major errors, though it was readily apparent that the increases were almost entirely due to schools in Clark County School District (CCSD), which covers the Las Vegas metropolitan area and accounts for 56% of the Nevada analysis sample. The figure below recreates the prior one, simply separating CCSD schools and those from the rest of the state.

Without CCSD, teacher absenteeism in all other Nevada schools took on a trajectory much like that observed in South Carolina (only modest increases in absence rates). Teacher absenteeism in CCSD, conversely, increased nearly 500% over its 2019 baseline. This increase is well beyond the absenteeism increases seen in other large urban school districts. For example, NYC went from 13% chronic absenteeism in fiscal 2019 to 19% in 2023, and Chicago went from 36% to 43% over the same period. To the best of our knowledge, CCSD has not changed teacher absence policies over the pandemic.

We consulted with Bradley Marianno about what might be going on there. Marianno is an associate professor in the University of Nevada – Las Vegas’s College of Education and Director of the Center for Research, Evaluation, and Assessment; he has partnered with CCSD to evaluate several policies and programs.

Marianno flagged two factors as particularly relevant in explaining excessive teacher absenteeism. First, CCSD adopted aggressive quarantine measures during the pandemic, requiring teachers to stay home when any of their students tested positive for COVID-19. CCSD was compelled to take a five-day break in January 2022 due to excess staffing shortages. The quarantine finally relaxed in August 2022, more than a year after the vaccine was broadly available to the public.

And second, the district also had ongoing labor disputes with the teachers’ union that prompted credible threats of sickouts in the 2022-23 school year, which might have contributed to increases. CCSD teachers eventually followed through with the sickout threat in the fall of 2023, affecting eight schools over seven instructional days. The 2023-24 school year is beyond the time span of the figures above, though is reported in the state teacher absence data: daily absences in CCSD schools in our sample increased yet again to an average of 29% in 2023-24. Clearly, CCSD has its work on reducing teacher absenteeism cut out for it.

Regardless of economic disadvantage, most schools have higher teacher absenteeism post-pandemic

Next, we focus on the differences in means by ECD status in the figures above (for the following discussion, we consider CCSD separately from the rest of NV). We highlight two patterns between ECD and non-ECD schools. First, in most states the ECD lines are consistently above the corresponding non-ECD lines, though the gaps between these lines are relatively small. The lines are so close to be nearly overlapping in the case of South Carolina, and ECD schools are slightly below non-ECD schools in the “rest of Nevada” series. Prior work has shown that teacher absenteeism is correlated with school economic disadvantage, though that correlation is very small. The patterns observed here seem to bear that out.

And second, the ECD and non-ECD lines in these same states move in parallel with each other over the years (as opposed to widening over time). Thus, the increases in teacher absenteeism appear to be similarly impactful in both kinds of schools, regardless of economic disadvantage.

Note that it’s possible that some of these changes could be driven by large changes in absenteeism in a few schools rather than representing modest changes in most schools. To examine this possibility, we plot the percentage of schools where post-pandemic absenteeism (2022-23) exceeds those schools’ pre-pandemic levels (2018-19) in the figure below. In all cases, we see that a strong majority of schools saw increases in teacher absenteeism.

Interestingly, absenteeism increased in the large majority of ECD and non-ECD schools alike. Furthermore, except for the “rest of Nevada” sample, non-ECD schools account for either the same or slightly more of those where teacher absenteeism has increased. This means that pandemic-era changes in teacher absenteeism depart from pandemic-era changes in student chronic absenteeism, where absenteeism increases have been much more pronounced among economically disadvantaged schools. Even in the “rest of Nevada” sample, the ECD and non-ECD school shares with higher absenteeism are nearly equal.

Focusing on teacher absenteeism may help with student recovery efforts

We began with a review of the various pieces of evidence pointing to increased teacher absenteeism in the wake of the pandemic. Our results from four geographically and politically diverse states corroborate these findings. They also show that, except for CCSD, increases in teacher absenteeism have been between about 20% to 50% above their baseline levels—posing meaningful, but not impossible, challenges for districts to overcome. The six-fold increase in teacher absenteeism in CCSD, however, constitutes a far outlier that warrants strong, corrective action.

We also find that changes in teacher absenteeism have not been correlated with student economic disadvantage in schools—a notable departure from other patterns based on student absenteeism and test scores in the wake of the pandemic. Examining the link between student and teacher absenteeism is beyond the scope of our analysis here, but teachers could still be a potential leverage point in learning recovery even if the correlational relationship appears to be more muted. More absent teachers mean higher demand for substitutes, who typically offer inferior teaching. More absent teachers may have a more difficult time building trusting relationships with students, which have been shown to drive student attendance and learning outcomes. More absent teachers may not be able to engage with parents effectively, who are also critical actors in prompting students to take attendance seriously. The increases in teacher absenteeism we observe in the large majority of schools can only be hindering recovery efforts.

Schools looking to reverse these trends should consult the helpful reports published by the National Council on Teacher Quality on the topic. Though we do not have evidence at scale about effective policies to counter teacher absenteeism, many approaches have been considered in the research literature and further experimentation is still warranted.

The pandemic abruptly changed the nature of teaching and has had long-term effects on students. We need to strategize about re-engaging teachers just as much as we need to re-engage students in recovery efforts.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank Nicolas Zerbino for data visualization assistance.

-

Footnotes

- Teacher absenteeism was a mandated reporting element in the CRDC between the 2009-10 through 2017-18 school years (data are collected on a biannual basis). It became an optional element for schools to report in 2021-22 (and, in practice, we do not see it reported in public-use files). Teacher absenteeism is a mandatory element again for the 2023-24 data collection wave, though these data are still being processed and are not currently available for research use.

- Because the high- vs. low-poverty school comparison is critical to our analysis, we dropped any schools where National School Lunch Program information was missing for the 2018-19 school year (2018-19 is used as a pre-pandemic anchor year).

- The Connecticut analysis sample consists of 963 schools; the CCD file reports 1,032 schools during our benchmark year (2018-19). The Illinois analysis sample consists of 824 districts; the CCD file reports 953 districts during our benchmark year (2018-19). The Nevada analysis sample consists of 631 schools; the CCD file reports 758 schools during our benchmark year (2018-19). The South Carolina analysis sample consists of 955 schools; the CCD file reports 1,283 schools during our benchmark year (2018-19). We should also note NV’s analysis sample overrepresents high-poverty schools, while SC’s sample underrepresents them. In South Carolina, school observations with missing teacher absence data (hence, dropped from the analysis files) had about 8 percentage points higher free-lunch eligible student shares than those that were retained in the analysis file, thus underrepresenting high-poverty schools. In Nevada, the schools missing teacher absence data were 11 percentage points lower in free-lunch eligible shares compared to those retained for the analysis; thus, high-poverty schools are overrepresented in the analysis file. Connecticut and Illinois analysis files showed no significant difference versus those observations that were dropped.

- Assuming that attendance and absence rates sum to 100%, we subtracted Nevada and South Carolina measures on daily attendance rates from 100%. Connecticut and Illinois already represent teachers missing school and are not altered.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).