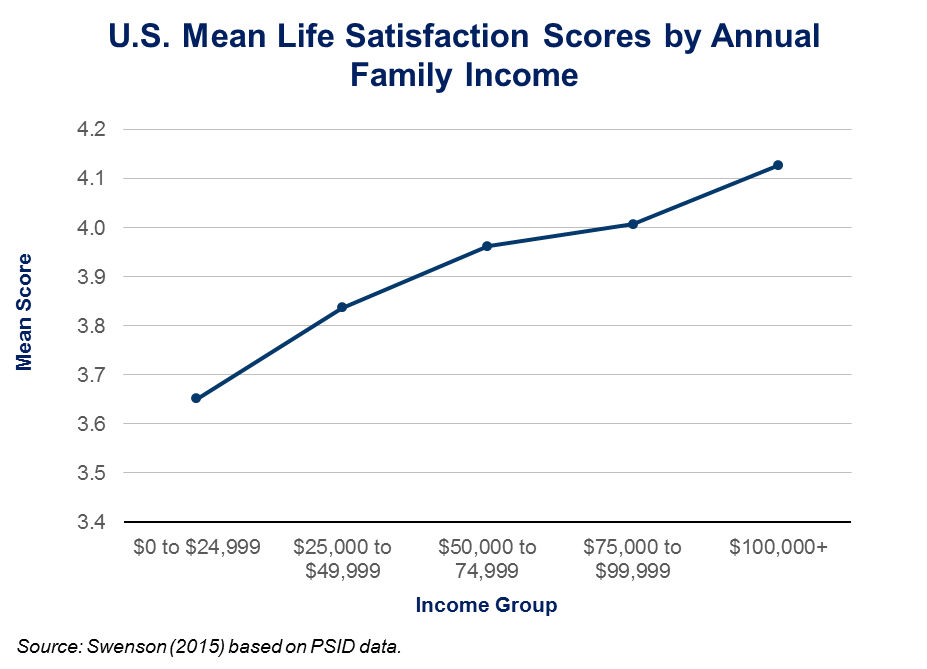

Poverty undermines well-being. Being poor in the United States is associated with lower life satisfaction, and with greater stress, pain, and anger. The opposite holds, too: more affluent people enjoy higher levels of well-being in general, in large part because wealthier people have better health, are less likely to be unemployed, and have more choices in life:

HOW MIGHT GOVERNMENT TRANSFERS AFFECT WELL-BEING?

Since income is related to well-being, what is the impact of government transfers? They may boost well-being by reducing hardship, particularly for those at the lowest levels of income. But on the other hand, people who are not self-sufficient may feel less self-worth and purpose. The unemployed are typically much less satisfied with their lives, even controlling for income, while individuals who report high levels of purpose and meaning in life score more highly in terms of well-being and are more likely to be employed, as one of us shows in a recent paper with Milena Nikolova. The bureaucracies accompanying some programs—especially those which are means-tested—are often less than user-friendly. Recipients of these transfers face various challenges—including stigma—during the application process.

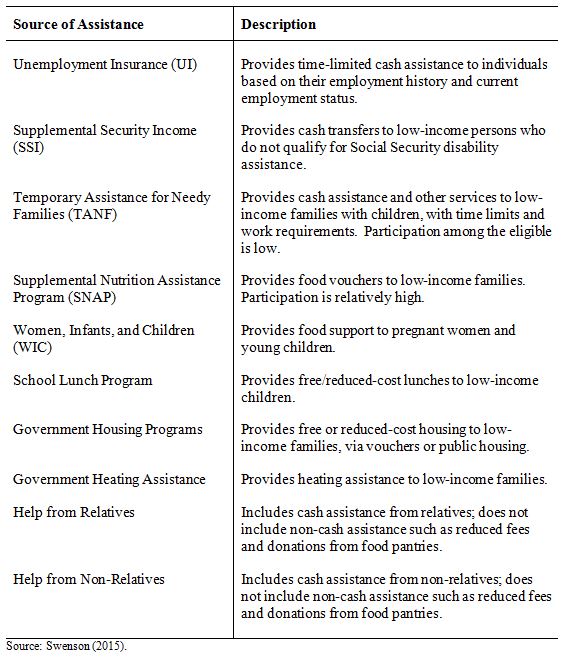

We examine the relationship between life satisfaction and financial assistance, both public (means-tested transfers) and private sources (family and charitable assistance) in the United States. See the Table below for categories of assistance:

SOURCES OF INCOME ASSISTANCE

ASSISTANCE LOWERS WELL-BEING

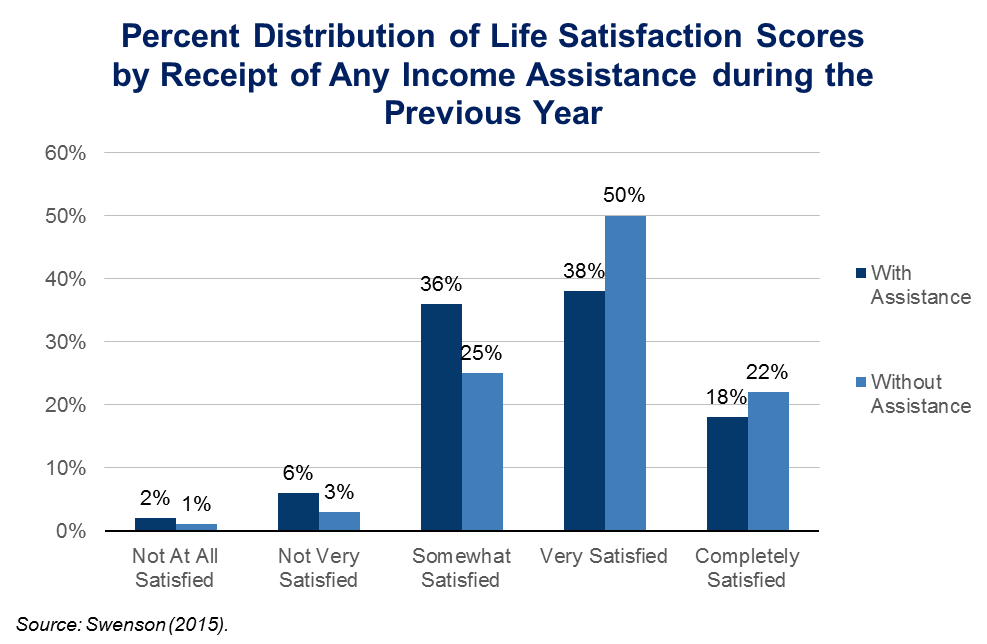

Recipients of transfers have lower levels of self-reported life satisfaction than non-recipients, controlling for income and other socio-demographic traits, according to an analysis of data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). The negative effects of receiving private transfers were equivalent to those from public transfers, an important finding given strong skepticism towards the impact of government assistance in public debates today:

The results presented are without controls for intervening factors, such as income and health, but show that transfer recipients are inevitably concentrated in the lowest life satisfaction categories. This is consistent with the creation of a vicious circle that we have identified elsewhere: low well-being = less likelihood of investing in the future = worse outcomes, including across generations. Causality likely runs in two directions: from environmental challenges—including reliance on transfers—to low levels of well-being; and from low levels of well-being to worse outcomes and the need to rely on transfers.

ASSISTANCE AND WELL-BEING: PROBABLY NOT A CAUSAL STORY

Why is receiving assistance associated with lower well-being? One explanation is stigma. This seems most likely to apply to the receipt of means-tested welfare assistance, but is a less plausible explanation for the similar effects of private and public transfers. However, private transfers may come with more conditions attached or be less predictable. Relying on such transfers may also be a way to cope with unstable or low-paying work or other circumstances beyond an individual’s control—the kinds of conditions that often bring stress and other markers of ill-being.

There may be a generation gap here, however. The adults answering the surveys may feel less positive about their own lives when they receive assistance. But since they likely seek it in order to provide basic necessities to their families, the result may be improved well-being for their children.

We also only capture a life-satisfaction measure. It may be that low-income families who go without assistance may have lower well-being outcomes in other areas, such as stress. We cannot observe in our data all the disadvantages that people who receive income assistance may have. Many contend with domestic violence, substance abuse, low aptitude, disabilities, discrimination, incarceration, and poor neighborhood conditions, among other challenges.

TRANSFERS HURT LESS FOR THE POOREST

The relationship between assistance and well-being varies across the income distribution, according to our analysis. For those in the bottom income quintile, the negative coefficient on receipt of transfers is less statistically robust, suggesting that those who need transfers the most feel fewer negative effects from receiving it. The most destitute families may experience hardship such that the benefits of assistance counter stigma effects. There are a number of challenges associated with deep poverty; the stress related to difficulties in obtaining basic necessities consumes energy and cognitive functioning to a degree that other priorities—including planning for the future—are set aside. Struggles with unpredictable hours and child care arrangements, as well as the unpleasant nature of poor quality and menial jobs, may far outweigh concerns about stigma.

In contrast, those who are higher up in the distribution may be relying on assistance to overcome a temporary negative shock (such as unemployment). They may feel more stigma from having to fall back on assistance (private or public), as it is less common for their socio-economic or professional reference group.

THE PRICE OF POVERTY

Our findings highlight the costs of being poor in a country where individual success is universally applauded. As Bob Putnam writes in his recent book, we have “privatized risk,” rather than recognizing that the collective benefits of helping the poor—and their children—catch up. Individuals with higher levels of life satisfaction are more likely to invest in their futures and, in turn, have better health, income, and other outcomes, which is good for society as a whole.

Many Latin American countries have reduced poverty and inequality in recent years through non-stigmatizing forms of income support, which hinge on recipients investing in their futures: enrolling their children in school and receiving preventive health care. But here in the United States, initiatives such as early childhood education, home visiting programs, and better coordination of existing services have insufficient support and resources. Perhaps we could take a page out the book of some of our near neighbors, and promote a shared societal stake in the next generation.

Kendall Swenson just completed his PhD at the University of Maryland. This blog draws on work undertaken for his dissertation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).