Executive Summary

Why, in spite of unprecedented economic interdependence in Northeast Asia, does the region remain so insecure? What in terms of policy can be done to assure a greater degree of stability and prosperity under these conditions?

To address these questions we begin by reviewing some of the principal analytical frameworks which provide a more textured understanding of the tensions that can exist between economic interdependence and security. In the second and third sections, we see how these analytical frameworks operate in the real world by considering current regional conditions of economic interdependence on the one hand and continuing security concerns on the other.

We find that in spite of encouraging developments in the economic sphere—such as expanding “new economic frontiers” in China, Vietnam and perhaps North Korea, rising intra-regional trade and investment, strengthened multilateral government cooperation in economic and financial realms, and continued strong economic “fundamentals” and commitment to intraregionalism—similar investments and “stakeholdings” in security have not been made on a regional scale. Rather, in the security sphere, caution constrains political investments owing to systemic weaknesses, persistent power rivalries, transnational problems, and domestic political forces which shape the region in a way that often undermines, rather than strengthens, stability for Northeast Asia.

As a result, a more comprehensive, ambitious, and long-term approach is necessary to assure continued economic interdependence and prosperity on the one hand, and steadily improved regional stability on the other. It is too early to expect a full-fledged regional security regime to adequately address the region’s security concerns. Rather, a more complex and interest-based set of concepts and policies—an approach we define as security mutualism is required [Mutualism: the doctrine or practice of mutual dependence as the condition of individual and social welfare.]. Security mutualism invests in interest-based mechanisms and promotes a greater degree of convergence across the region in both socioeconomic and political terms.

Based on these understandings we conclude with a set of policy recommendations for regional governments:

Overall framework

- Integrate concepts of common security and security mutuality, rather than unilateral security, into regional policy thinking in the region over time. This approach resonates with deeply-embedded security thinking in the region. Here it may be useful to build on concepts of “investors”, “stakeholders”, and “policyholders” as a means to illustrate the commonality of interests.

- Achieve a greater degree of convergence in the level of socioeconomic development among concerned parties in the region. This is a particularly important condition for resolution of differences on the Korean peninsula and across the Taiwan Strait. Since this process is likely to take decades rather than years, successful regional and bilateral reconciliation should be seen as a long-term goal.

- Recognize the necessity for small-scale interim measures which are functional, often ad hoc, and based first and foremost upon mutual interests.

Regional

- Focus on Northeast Asia-centered mechanisms for multilateral and bilateral dialogue: region-wide, “ad hoc” mechanisms, “minilaterals”, and unofficial “track two” efforts.

- Stabilize regional economic interdependence through such organizations as APEC and the WTO, and continued exploration of subregional economic integration and consultation initiatives such as ” ASEAN + 3″, and an Asian Monetary Fund.

- Establish a Northeast Asian inter-parliamentary mechanism to promote exchanges among legislative bodies of China, Hong Kong, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, Russia, South Korea and Taiwan.

- Strengthen government commitments to “track two” exchanges aimed specifically at addressing Northeast Asian security concerns, with the long-term aim of developing region-wide approaches which can accommodate the fundamental security interests of regional players. Items on the track-two agenda should include: TMD/NMD; regional arms control mechanisms to manage the offense-defense dynamic emerging in the region; future U.S. force structure in Northeast Asia; and the utility and limits of security alliances in the region.

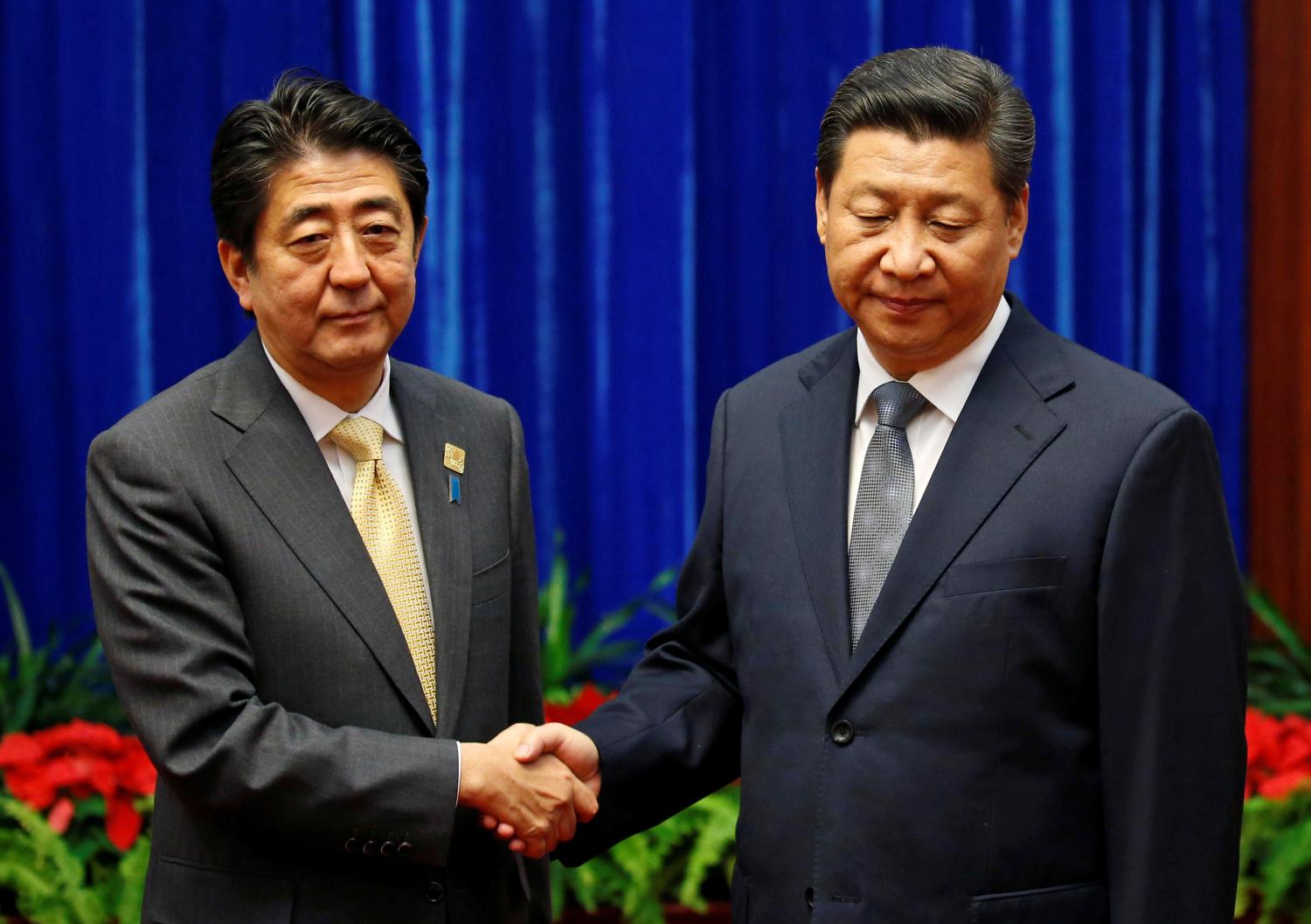

- Promote “minilaterals” among interested parties (such as China-Korea-Japan; Russia-China-Japan; US-Japan-China) to consult on regional economic and security issues. China-Japan-US triangular relations in particular hold the key to stability in the region. Leaders of these powers should meet regularly (around the annual APEC Summit, for example) to discuss issues of common concern.

- Support ad hoc multilateral groupings designed to address specific issues amenable to multilateral solutions in Northeast Asia; the current Four-Party and KEDO processes are good examples.

Bilateral

- Intensify dialogue, consultation, and summitry at the highest levels on certain bilateral disputes such as across the Taiwan Strait, on the Korean peninsula, and between Japan and Russia. However, while constructive contributions would be welcome, regional third parties should understand that divisions between North and South Korea on the one hand, and between China and Taiwan on the other are basically questions of nation-building, and are best addressed by the bilateral parties involved.

- Broaden social, political and economic exchanges across the Taiwan Straits, including direct links in trade, investment, shipping, postal service, and passenger flights, as well as improved dialogue on their respective sociopolitical institutions and infrastructures. All sides on the Taiwan Strait issue must do their utmost to avoid conflict.

- Acknowledge the security benefits of the bilateral alliance system in the absence of a more region-wide security structure, while at the same time accepting the need to reform that system to integrate greater regional consultations and concepts of common security and security mutualism.

Unilateral

- Invest greater financial and political resources to tackle a more ambitious agenda of regional engagement and consultation at bilateral and multilateral levels.

Security Mutualism: Investing Stakes in a Prosperous and Stable Northeast Asia

I. Introduction: Interdependence vs. Security

Why, in spite of unprecedented economic interdependence in Northeast Asia, does the region remain so insecure? What in terms of policy can be done to assure a greater degree of stability and prosperity for the region? In order to offer answers to these questions, we begin by considering some of the principal frameworks and analytical approaches which have dealt with this question in the past, and go on to review what previous analysts have to say about the relationship between interdependence and security.

In the second and third sections, we see how these analytical frameworks operate in the real world by considering current regional conditions of economic interdependence on the one hand and continuing security concerns on the other. We find that in spite of encouraging developments in the economic sphere—such as expanding “new economic frontiers” in China, Vietnam and perhaps North Korea, rising intra-regional trade and investment, strengthened multilateral government cooperation in economic and financial realms, and continued strong economic “fundamentals”—similar investments and “stakeholdings” in security have not been made on a regional scale. Rather, in the security sphere, caution constrains political investments owing to systemic weaknesses, persistent power rivalries, transnational problems, and domestic political forces which shape the region in a way that often undermines, rather than strengthens, stability for Northeast Asia.

As a result, a more comprehensive, ambitious, and long-term undertaking is necessary to assure continued economic interdependence and prosperity on the one hand, and steadily improved regional stability on the other. It is too early to expect a “one size fits all” regional security regime to adequately address the region’s security concerns. Rather, a more comprehensive and forward-looking set of concepts and policies an approach we define as security mutualism is required. Based on these findings we offer in a concluding section a set of policy recommendations for the regional governments.

Three perspectives on the question

Before taking up the descriptive and prescriptive aspects of this work, it would be useful to first consider several analytical frameworks or “lenses” through which to understand the interdependence problematique which Northeast Asia confronts.

First, a neo-realist, or “power politics” perspective on this question points out that nation-states are driven by the pursuit of power in a zero-sum, anarchic world where one country’s gain is another one’s loss. In order to compensate for others’ gains, states react by seeking to augment their security and national power. Neo-realists see international cooperation as hard to achieve, difficult to maintain and dependent on state power to succeed. In this view, because international anarchy requires states to be preoccupied with issues of security and survival, cooperation often is not given a high priority unless it serves a fundamental national security interest. As such, neo-realists concentrate on state power and capabilities rather than declarations of intent. For many, the situation in Northeast Asia stands out as a primary example of neo-realist understanding, where, for example, tension between the two Koreas, between China and Japan, and across the Taiwan Strait poignantly illustrates the classic security dilemma in spite of increased economic interdependence between and amongst these powers.

Another perspective – often known as an “institutionalist” view – would look at this question differently. This analytical approach suggests that both political and economic institutions can serve as a mechanism for achieving international security. Although liberal institutionalism accepts many neo-realist assumptions about power politics, it suggests that institutions can provide a framework for cooperation and moderate the dangers of security competition between states. According to this school of thought, institutions offer information, reduce transaction costs, establish coordination nodes, and smooth the way for reciprocity and mutualism to work.

Looking at Northeast Asia, institutionalists would quickly point to the successes of such mechanisms as the Four Party Talks, the US-North Korea Agreed Framework, the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO), and the cross-Straits dialogue between the Association for Relations Across the Straits (ARATS) and the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF). However, institutionalists would likely concede that the region still lacks sufficient investment in security-enhancing mechanisms to help manage the area’s security problems.

Finally, a social constructive interpretation to this question takes yet another approach. This school of thought addresses issues typically ignored by the neo-realist and neo-liberal schools by focusing on the content and sources of state interests and the social fabric of international politics. It emphasizes the point that states take actions in the international arena which are social as well as material, and this setting provides states with a way to interpret their national interests. This thinking assumes that material structures are given meaning only by the social context through which they are interpreted, and emphasizes a process in which state interests emerge from and are endogenous to interaction with the international structure. Identities and norms therefore constitute states, providing them with understanding of their national interests.

As such, social constructivists explain the cause of war in terms of the conflicting identities of given polities. For example, it would see the conflict between China and Taiwan in terms of a clash of two distinct identities. Without a shared understanding of political reality to redefine mutual interest as well as to develop a collective identity economic interdependence alone simply can not ameliorate the security dilemma. Hence, conflict persists.

What do these frameworks tell us?

While each of these interpretations looks at our question from a different angle, they all help us understand in a more fundamental way why, despite increased economic interdependence, Northeast Asia continues to lack security. Realists remind us that in spite of increased degrees of interaction and cooperation, states continue to operate with parochial self-interest in mind. Liberal institutional thinking explains that institutions can alleviate destabilizing outcomes from such narrow self-interest, but would acknowledge that Northeast Asia lacks adequate structures in this regard. Constructivists would see Northeast Asian insecurity as deriving from a poor sense of collective interests as societies.

Taking a cue from these frameworks, we would argue for a mutualistic approach which invests in interest-based mechanisms and promotes a greater degree of convergence across the region in socioeconomic and political terms.

II. Deepening Economic Mutualism in the Region

In a sense, a mutualistic approach to regional relations is already well-established in terms of economic interdependence. The pattern of economic development in post-war East Asia has been likened to a flock of geese flying in ‘V’ formation. In Northeast Asia, the development process first began in Japan, rippled out to the Asian newly-industrialized economies (NIEs) such as Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan and eventually spread to the economies of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) and China.

Traditionally these economies have depended heavily on the United States for trade and investment but the trend towards intra-regional economic interdependence has accelerated since the Plaza Accord in 1985. The end of the Cold War has also helped promote the integration of the socialist countries (such as China, Vietnam, and even North Korea) into the regional economy. While strengthening ties among these economies has until now been achieved mainly through the initiative of the private sector, multilateral economic cooperation at the government level is also gaining momentum. Economic integration may also facilitate the convergence of sociopolitical interests over time.

Expanding New Frontiers across Old Borders

During the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War, adherents of the domino theory predicted that if Vietnam were to fall to Communism the rest of Southeast Asia would follow. Ironically, with transitions to market economies gathering pace in the region’s socialist countries, in conjunction with Cold War ideological and geopolitical barriers slowly diminishing, the reverse is now taking place. In this environment of mutual economic interests, China, Vietnam and, possibly in the future, North Korea—are emerging as the region’s new economic frontiers, in effect creating economic zones encompassing countries with different economic and political systems at various stages of economic development.

China has become the region’s largest new frontier and plays a particularly pivotal role in Northeast Asia’s economic integration. With a population of more than 1.2 billion and its economy growing at nearly 10 per cent a year since converting to an open-door policy in the late 1970s, it is emerging as a regional, if not global, economic power. China’s transformation to a market economy and its opening to the world has had an integrative effect on neighboring countries. China can now present itself as a model for other socialist countries in the region to follow, and thereby accelerates the reverse-domino phenomenon. Also, Asian NIEs have and should continue to benefit from expanding investment and trade ties with China. This is particularly true for Hong Kong and Taiwan whose populations are predominately Chinese, and who share linguistic and cultural similarities with mainland China.

Intra-regionalization of trade and investment

Until the mid-1980s, trade in East Asia had been dominated by exports across the Pacific, a trade-flow pattern that has changed dramatically since the 1985 Plaza Accord, which resulted in a sharp appreciation of the yen against the dollar. With East Asia growing at twice the speed of the United States and the escalation of trade friction between the two sides of the Pacific, intra-regional trade among East Asian countries has increased sharply, while the relative importance of the US as an export market has declined.

In East Asia, Japan has replaced the US as the largest source of foreign direct investment, while the Asian NIEs have also become major investors in China and the ASEAN countries. Currency appreciation in Japan and in the Asian NIEs since the 1985 Plaza Accord prompted many companies to move their production facilities overseas. Not only is Japan playing an increasingly important role in other East Asian economies, but now Japan’s own economic fortune also hinges on the performance of its Asian neighbors. During the Cold War period, Japan became highly dependent on the US, not only for its defense but also for the export market and technology that has supported the Japanese economic miracle. With the fading of the Cold War, the re-Asianization of the Japanese economy has gathered momentum. Rising trade friction with the US (push factor) and rapid economic growth in the East Asian economies (pull factor) further accelerates this trend. The growing importance of East Asia for Japan has become apparent in trade and investment flows. Indeed, East Asia has replaced the US as Japan’s most important export market and in the future it may also replace the US as the most important destination for Japanese investment.

Strengthening Multilateral Government Cooperation

While economic integration in East Asia so far has been achieved mainly through private initiatives, multilateral economic cooperation at the government level, such as Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), is also gaining momentum.

The APEC forum is emerging as the dominant force for economic cooperation in the Pacific region. Since the first ministerial meeting in 1989, APEC’s role has centered on the promotion of dialogue and cooperative sectoral projects to deal with the major problems affecting the regional economy. At the 1994 Jakarta APEC summit, participants agreed to a dual-speed schedule, stipulating that trade and investment liberalization be completed by 2010, for advanced member countries, and by 2020 for developing member countries.

Other government-based initiatives to further promote regional economic integration include forming an East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC), as proposed by Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad. Although EAEC has failed to materialize, largely because of opposition by the US, the annual “ASEAN + 3 Informal Summit” with the participation of China, Japan and South Korea may represent a step in this direction.

The Asian Currency Crisis

The financial crisis that infected the whole region in mid-1997 showed how a virtuous cycle between increasing interdependence and high economic growth could turn into a vicious one. Escalating speculation on the baht forced Thailand to abandon the basket peg exchange-rate system and shift to a managed float regime on July 2, 1997. This was accompanied by a sharp devaluation of the Thai baht which spread to the currencies of neighboring countries. One after another, Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea had to seek financial support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Sharp currency depreciation aggravated the bad-debt problem facing East Asian banks, who in turn found it difficult to raise funds in international capital markets. The resulting credit crunch problem, together with austerity measures implemented to reduce trade deficits, sharply depressed economic growth in the region.

Several key lessons clearly emerged from the crisis. For the purpose of this research, we note that further international cooperation among monetary authorities, in the form of establishing an Asian Monetary Fund that complements the IMF, is needed to contain the contagion effect. An agreement to expand a foreign exchange reserve swap reached in May 2000 among 10 ASEAN countries, China, Japan and South Korea to support one another’s currencies during times of crisis represents a major step in this direction. Moreover, ASEAN and APEC, which failed to play a constructive role in preventing the crisis from deepening and widening, should broaden their economic agendas from focusing solely on trade liberalization to included macroeconomic policy coordination. More broadly, the exposure of the major shortcomings in the current international financial system has led to serious discussions among monetary authorities in search of a “new international financial architecture.”

In addition, the Asian Crisis has also cast doubt over the sustainability of the East Asian miracle; however, the basic factors contributing to the Asian miracle—high savings rates, heavy investment in human resources and market-friendly economic policies—are not likely to change as a result of the crisis. Indeed, the countries in the region have devoted an immense amount of effort to address the structural problems they face, and their economies have shown clear signs of recovery since 1999.

III. Current Security Concerns

It is clear that in Northeast Asia economic interaction and deepening economic mutualism do not in and of themselves provide security: they do not necessarily offer solutions to security issues, create mechanisms or institutions guaranteeing security, nor do they fully induce convergent conceptions of political differences and similarities. Indeed, in spite of rising economic mutualism in Northeast Asia, many security concerns persist. These concerns are well known, and can be briefly summarized below under five principal categories: systemic factors, power rivalries, transregional problems, domestic political concerns, and the future role of the United States.

Systemic weaknesses

First, at a systemic level, economic interdependence has not increased symmetrically throughout Northeast Asia; likewise, military strength also is not equally and uniformly distributed. North Korea’s isolation and economic difficulties, as well as China’s developing nation status, clearly illustrate the lengths to which the region must still go in order to raise the level of economic modernization on a region-wide basis. Although the United States largely dominates the region from a military-technical point of view outstripping the basic military capabilities and defense spending of all the other regional governments combined regional concerns regarding China and Japan’s military modernization programs persist unabated. These economic and military issues contribute to larger systemic concerns about regional interdependence and security.

Second, increased economic interdependence has not broken down lingering systemic suspicions that undermine a sense of community within the region. These problems are attributable to historical animosities, often associated with World War II hostilities, but some of which also date back many centuries. Past animosities compounded by a lack of political will in the present, can potentially hinder significant political cooperation in the future.

Finally, Northeast Asia lacks an effective regional security arrangement. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), while building up its capabilities to foster greater confidence building measures (CBMs) has not yet addressed the most pressing security concerns of Northeast Asia. The system of bilateral alliances, which has characterized the region since the end of World War II, has fostered a sense of security for many regional governments, particularly during the Cold War. However, this system has come under intense scrutiny with the collapse of Soviet-led alliances, the fall of the Soviet Union, and especially with the end of the Cold War. Concurrently, the continued existence of US bilateral alliances is viewed by many as beneficial as a means to maintain security in the absence of a more effective regional security structure. In this view, not only do bilateral alliances contribute to security, but they also diminish the incentive for individual parties to seek other regional security arrangements.

As a result of these various considerations, regional parties hold different views about the systemic nature of security in Northeast Asia. Official US and Japanese views tend to envisage an alliance-based security order, while official Chinese and Russian pronouncements advocate a pluralistic security community, which means that all regional members cooperate in enhancing regional stability. This divergence not only leads to different approaches to regional security issues, but also impedes efforts to establish more cooperative relations among major powers.

Nevertheless, the region has not experienced an all-out-war since 1953 when an armistice was signed on the Korean Peninsula. In other words, a state of passive systemic peace has been maintained for almost five decades in this tension-ridden area a point which is important to remember. The current balance of power in the region is not a precise reflection of Great Britain’s role in 18th and 19th century Europe. Rather, the United States, as the sole post-Cold War hegemon, plays the role of “stabilizer” rather than “balancer”. Second-tier powers, China, Russia and Japan, have neither the willingness nor capability to challenge US hegemony, and there is little possibility of Sino-Japanese collusion aimed at challenging the United States. Instead, Tokyo and Beijing seek a positive relationship with the US, thus straying from classical balance of power behavior.

Power rivalries

In addition to broad systemic differences, although they are basically normal and much improved in comparison with the Cold War era, specific relationships and rivalries among the major powers in the region remain far from stable. Two regional hotspots in particular—the Taiwan Straits and a divided Korea—remain unresolved. Cold War calculations continue to affect these rivalries, and threaten to draw in other major powers during a crisis. Some cases—such as the dispute across the Taiwan Strait and conflicting Japanese and Russian territorial claims—do not easily lend themselves to resolution through a broader region-wide process. These bilateral rivalries need to be pushed further toward resolution as a way to improve the overall security environment. Recent developments on the Korean Peninsula, the summit between Kim Dae-Jung and Kim Jong-Il, as well as reunions between families divided during the Korean War demonstrate how bilateral can have a stabilizing effect in the region.

More broadly, while several bilateral relations do not at the moment present themselves as overt and pressing problems, their long-term stability is not guaranteed. For example, how should the region manage continued growth of power and influence on the part of China and Japan in ways that do not rekindle age-old rivalries? How will the region’s most powerful player, the United States, accommodate rising Chinese and Japanese roles over time?

Transregional threats

Because of the interrelatedness of security in Northeast Asia, the importance of transregional security issues cannot be dismissed. To the degree that these transregional issues affect most or all of the region’s actors, there is a greater likelihood that an approach of security mutualism can be built to address the problem. For example, a mutually-held understanding of the importance of stability on the Korean peninsula led China, the United States, and the two Koreas to open the Four Party Talks, and has encouraged both Seoul and Tokyo to call for Six Party Talks to bring Russia and Japan into the process. The establishment of KEDO is another example of how mutual interests lead governments to establish appropriate security-oriented mechanisms.

Weapons proliferation is another transregional issue around which Northeast Asian actors can meet to pursue mutual interests. The major players in the region either have nuclear weapons (China, Russia, the United States and possibly North Korea) or are technologically capable of developing them (Japan, South Korea and Taiwan). Similar descriptions can be made about possession and capabilities vis-à-vis medium- and long-range ballistic missiles: China, North Korea, Russia and the United States all possess them, both South Korea and Taiwan could do so (with some evidence that they are pursuing this level of capability), and Japan, with satellite launch capacity, has shown it is capable of developing ballistic missiles if it chooses. Moreover, the development of missile defenses proceeds apace in the region in reaction to ballistic missile build-ups. Mutually beneficial steps can and should be taken in order to avoid an arms race in Northeast Asia.

Domestic politics

In addition to these international concerns, we would also draw attention to domestic developments and their impact on regional security. First, generational political change is an important factor to watch. The political systems of the major players in the region—Japan, Russia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan—are undergoing significant political evolutions. A handover to a “fourth generation of leadership” in China is expected in 2002, though its outcome is far from certain. Many informed observers in China believe that the country will go through far-reaching political change in the next five to ten years in response to the internal pressures of unprecedented socioeconomic transformation. Japan continues to grapple with coalition politics as a new generation of more independently-minded politicians come to the fore to challenge shibboleths in domestic, alliance, and international arenas. New leadership in Russia holds a number of uncertainties for the future direction of a Russia seeking renewal and rejuvenation in the decade ahead.

On the Korean peninsula, President Kim Dae-jung’s ascent to power dramatically changed the course of inter-Korean relations, leading to the June 2000 summit with Kim Jong Il; these developments must outlast transitions of power in both capitals over the coming years. The continued democratic evolution of Taiwan—illustrated most recently with the election of opposition leader Chen Shui-bian—signals new and more complex foreign and security relations across the Taiwan Strait.

Second, these trends point to continuing and increased salience of democratization and pluralization in order to understanding foreign and security policy in the region. On the one hand, democratization and generational change can facilitate peace and prosperity in the region given that younger generations may be more pragmatic and functionally-oriented, less ideological, more materialistic, and more internationally-minded. On the other hand, younger generations may pursue national interests more aggressively; the lack of wartime experience and unawareness of the atrocities of war may make them attempt bolder approaches without prudence or self-restraint. A worst-case scenario would be the convergence of democratization combined with emotional nationalism. In any event, democratization in the region brings with it new foreign and security policy challenges as leaders must be more responsive to potentially volatile publics while seeking to build a middle ground around prudent long-term interests.

Role of the United States

As scholars from Northeast Asia familiar with the United States, we find it necessary to provide views about the US role in the region from a Northeast Asian perspective. In general we find it interesting that the United States, as the only major power more or less accepted by others in the region, has shown little willingness to leverage this influence more actively. Even accepting the fundamental and currently stabilizing role of US alliances in the region, Washington has done little to look beyond this structure to consider a more integrated or comprehensive approach consistent with the region’s economic and security dynamic.

Rather, in sharp contrast with frequent remarks by some US officials on the unpredictability of the Northeast Asian security situation, Washington’s attention overall remains fixed on European affairs. Certainly the economic interdependence between the United States and Northeast Asia travels far ahead of the American consciousness toward the region. As a result, we are often concerned with a degree of “benign neglect” and inattention to America’s role as a stabilizer in the region on the one hand, and a degree of ham-handedness and cavalier approaches to security on the other. At present, a more judiciously engaged American leadership is needed.

Without taking a position here on the wisdom of missile defenses, we sense that a concern for the broad regional security situation and the opinion of allies has not been adequately taken into account as a part of deployment decisions. In addition, we support the idea of giving greater consideration to approaches which emphasize “reliable reassurance” in order to moderate and complement “overwhelming deterrence.” Given the fundamental importance of the US role in maintaining and promoting regional prosperity and security, it is critical that American leaders devote more comprehensive consideration and attention to this part of the world.

IV. Recommendations

Thus, many questions arise at the nexus of economics and security that lie at the heart of our inquiry. How will China’s emergence as an economic power translate in terms of its military strength? Can the rise in economic interdependence provide the necessary framework to alleviate security tensions on the Korean Peninsula? Between China and Taiwan? Accommodate a more powerful Japan and China? Integrate North Korea as one of the region’s “new economic frontiers”? While complete answers to these and other questions are not readily apparent, we believe that an approach which gives greater weight to the notion of “security mutualism”—while not perfect—holds out great promise.

We base our findings on three important factors. First, while holding generally to the neo-Realist understanding of state interests, we are not dissuaded from the merits of interests-based institutionalism and the need to foster a greater degree of sociopolitical convergence amongst the region’s societies. Second, we find that economic mutualism and interdependence have been critical factors in the successful prevention of war in Northeast Asia for nearly five decades. Finally, given these findings, we are persuaded that greater efforts should be undertaken to build upon the accomplishments of economic interdependence in order to invest more wisely and effectively in an interest-based security mutualism.

Such an approach would seek to gradually integrate many or all of the following policies:

Overall framework

- Integrate concepts of common security and security mutuality, rather than unilateral security, into regional policy thinking in the region over time. This approach resonates with security thinking in the region. Here it may be useful to build on concepts of “investors”, “stakeholders”, and “policyholders” as a means to illustrate the commonality of interests and potential policy dividends.

- Achieve a greater degree of convergence in the level of socioeconomic development among concerned parties in the region. This is a particularly important condition for resolution of differences on the Korean peninsula and across the Taiwan Strait. Since this process is likely to take decades rather than years, successful regional and bilateral reconciliation should be seen as a long-term goal.

- Recognize necessity for small-scale interim measures which are functional, often ad hoc, and based first and foremost upon mutual interests.

Regional

- Focus on Northeast Asia-centered mechanisms for multilateral and bilateral dialogue: region-wide, “ad hoc” mechanisms, “minilaterals”, and unofficial “track two ” efforts.

- Stabilize regional economic interdependence through organizations such as APEC and the WTO, and continue exploration of subregional economic integration and consultation initiatives such as “ASEAN + 3”, an Asian Monetary Fund.

- Establish a Northeast Asian inter-parliamentary mechanism to promote exchanges among legislative bodies of China, Hong Kong, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, Russia, South Korea and Taiwan.

- Strengthen government commitments to “track two” exchanges aimed specifically at addressing Northeast Asian security concerns, with the long-term aim of developing region-wide approaches which can accommodate the fundamental security interests of regional players. Items on the track-two agenda should include: TMD/NMD, regional arms control mechanisms to manage the offense-defense dynamic emerging in the region, future U.S. force structure in Northeast Asia, and the utility and limits of security alliances in the region.

- Promote “minilaterals” among interested parties (such as China-Korea-Japan; Russia-China-Japan; US-Japan-China) to consult on regional economic and security issues. China-Japan-US triangular relations in particular hold the key to stability in the region. Leaders of these powers should meet regularly (around the annual APEC Summit, for example) to discuss issues of common concern.

- Support ad hoc multilateral groupings designed to address specific issues amenable to multilateral solutions in Northeast Asia; the current Four-Party and KEDO processes are good examples.

Bilateral

- Intensify dialogue and consultation at the highest levels on certain bilateral disputes such as across the Taiwan Strait, on the Korean peninsula, and between Japan and Russia. However, while constructive contributions would be welcome, regional third parties should understand that divisions between North and South Korea on the one hand, and between China and Taiwan on the other are basically questions of nation-building, and are best addressed by the bilateral parties involved.

- Broaden social, political and economic exchanges across the Taiwan Straits, including direct trade, investment, shipping, and postal service links, passenger flights, as well as improved dialogue about their respective sociopolitical institutions and infrastructures. All sides on the Taiwan Strait issue must do their utmost to avoid conflict.

- Acknowledge the security benefits of the bilateral alliance system in the absence of a more region-wide security structure, while at the same time accepting the need to reform that system to integrate greater regional consultations and concepts of common security and security mutualism.

Unilateral

- Invest greater financial and political resources to tackle a more ambitious agenda of regional engagement and consultation at bilateral and multilateral levels.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).