While the deficits of public pension plans have been widely discussed, much less attention has been given to the obligations of US local governments to supply healthcare for their retired employees.

The unfunded liabilities for retiree healthcare for the 30 largest US cities exceeds $100bn, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts, a Philadelphia-based non-profit organisation. The unfunded liabilities for the 50 US states exceeds $500bn, according to Standard & Poor’s, the rating agency.

Retiree healthcare plans are uniquely American. They exist because the US has never offered universal healthcare before Medicare, the national social insurance programme, at age 65.

Many employees of cities and states retire between 50 and 55, so local governments usually provide them with highly subsidised healthcare between retirement and Medicare, and sometimes beyond.

Yet retiree healthcare plans of local governments, on average, have less than 10 per cent of the funding they need to meet their future obligations. By contrast, if a public pension plan were less than 60 per cent advance funded, it would be considered to be in dire straits.

Given this low level of advance funding, most cities and states have to pay the healthcare costs of their retirees out of their current tax revenues. As these healthcare costs rise, they will begin to crowd out other important local functions such as schools and police. And the overhang of unfunded obligations for retiree healthcare will adversely affect the bond ratings of local governments.

Fortunately, three recent developments are likely to lead to significant reforms of retiree healthcare plans in the US: new accounting rules on plan liabilities, new judicial guidance on collective bargaining agreements, and the Cadillac tax on high-cost healthcare plans.

First, the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, the independent organisation that sets reporting requirements for US state and local governments, recently adopted big improvements to its disclosure regime.

Effective in 2017, the new GASB rules will mandate that state and city governments include liabilities for retiree healthcare on public balance sheets, rather than in obscure financial footnotes, as previously. This should focus more voter attention on unfunded healthcare obligations.

GASB also declared that all local governments should use the same discount rate, the interest rate on AA-rated municipal bonds, in calculating unfunded healthcare liabilities. The discount rate represents an assumed investment yield when figuring out the amount of current assets needed to finance future benefits. However, many local governments have been assuming much higher yields than the current 3 per cent on AA-rated municipal bonds, thus materially understating the long-term cost of their retiree healthcare obligations.

Second, the Supreme Court recently decided that a collective bargaining agreement should not be construed to provide workers with free healthcare benefits for life, unless that agreement explicitly promised such a lifetime guarantee. Instead, the court declared that, under general principles of contract interpretation, healthcare benefits included in such an agreement should expire when the agreement ends.

Although this case dealt with a healthcare plan in the private sector, it should apply to collective bargaining agreements in the public sector, since the case delineated general contract principles. In the public sector, most collective bargaining agreements do not expressly continue healthcare benefits in perpetuity. As these agreements expire, local governments will have the opportunity to renegotiate their healthcare benefits with public unions.

Third, in these negotiations, local governments should be very concerned about becoming subject to the Cadillac tax on high-cost healthcare.

Cities and states offer relatively generous healthcare plans to their employees and retirees. In 2014, the cost of government healthcare plans was 17.5 per cent higher than the average private sector plan, according to United Benefit Advisors, a network of employee benefits advisory companies.

Congress passed the Cadillac tax to discourage employers from offering very expensive healthcare plans. This is a 40 per cent tax on the total healthcare premiums (from the employer and its employees) exceeding a specified limit — $27,500 for a family in 2018.

Although Congress delayed the effective date of the Cadillac tax until 2020, the threat has already led some local governments to pare back their retiree healthcare plans.

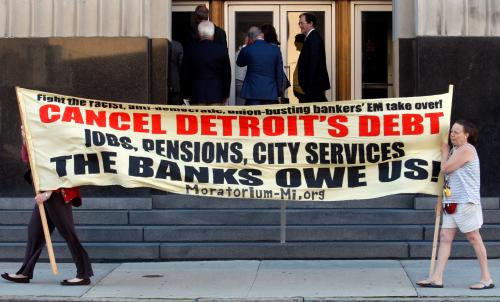

In short, the unfunded liabilities for retirement healthcare could bust the budgets of many cities and states over the next decade. However, local governments will come under tremendous pressure to constrain these liabilities.

Editor’s note: This piece originally appeared in the Financial Times.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edRetirement healthcare could bust the budgets of many US cities

August 1, 2016