During Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional hearing this October, congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) asked the Facebook CEO whether she could run advertisements on Facebook “targeting Republicans in primaries saying they voted for the Green New Deal.” The resolution, for which she is the sponsor, has never been voted on in the House. A representative for the company later confirmed to CNN that AOC’s proposed ad would probably be just fine since Facebook’s fact-checking policy does not extend to politicians.

The New York Times reported last month that political campaigns were pressuring Facebook to continue its policy not to fact-check political advertisements. Facebook, so far, seems eager to hold its position.

All of this adds to the list of grievances against the social networking site, which have metastasized since the 2016 election. But are the fact-checking rules any different for Facebook than they are for cable television?

Political ads by politicians are, by and large, not required to be fact-checked the way commercials for consumer products are. And the recent news around Facebook’s procedures related to advertising is important, not only because it highlights the role of digital platforms in electioneering, but because it exposes the glaring gaps in regulation around political ads more broadly.

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) administers rules for political programming; these rules pertain to the specifics around political advertising such as sponsorship disclosures. And the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is tasked with regulating commercial advertising. The FTC protects consumers from false advertising by companies through its “Truth in Advertising” standard but political campaigns (and politicians) have been largely exempt from advertising requirements on the grounds of free speech.

Take for example the 1972 campaign of white supremacist J.B. Stoner, a primary contender in Georgia’s U.S. Senate race. During the race, cable networks broadcasted Stoner advertisements ridden with racist tropes, at one point telling viewers to vote for “white racist J.B. Stoner.” When the Atlanta NAACP and other groups protested the ad, the FCC ruled that refusing to air political ads would interfere with Stoner’s right to free speech. Running for governor of Georgia in 1978, Stoner produced similar ads and, again, the FCC ruled in Stoner’s favor.

Cable networks have, however, developed norms around fact-checking political advertisements over time. Just last month, CNN rejected two ads from President Trump’s re-election campaign because of inaccuracies. These ads were eventually published on Facebook and other digital platforms as part of a multimillion-dollar ad buy. In Sen. Mark Warner’s (D-Va.) October letter to Mark Zuckerberg, he urged the Facebook CEO to “adhere to the same norms of other traditional media companies.”

But is this enough? That networks and traditional media have developed norms does not necessarily make theirs the right approach. The spread of disinformation in the 2016 election—most notably through Facebook—has shown that norms in traditional media are not transferring to digital platforms. And problematic ads from the pre-digital era show that these norms are not enough to protect consumers from flagrantly false information in political advertisements.

As inaction persists at the federal level, states have taken policy into their own hands in regard to state-based races. As of 2014, 27 states prohibit false statements in advertisements, but courts have struck down laws in four of those states. Washington provides an example of what could happen in states that are considering legislation about disinformation in political advertising and those that have already adopted such regulation.

For example, in 1998 the Supreme Court of Washington State struck down a 1984 state statute that prohibited sponsoring political advertising that “the person knows, or should reasonably be expected know, to be false,” arguing that the measure was in defiance of the First Amendment and that it had a “chilling effect” on free speech. Dissenting, Judge Philip Talmadge said that the Washington Supreme Court became “the first court in the history of the Republic to declare First Amendment protection for calculated lies.”

In the ruling, the court suggested that the law could be upheld if it considered defamatory false statements. So, the legislature altered the statute in 1999 to include protections for candidates against falsities “with actual malice.” Then in 2009, the court again struck down the statute in Rickert v. Washington. Two years later, the legislature amended the statute to include a detailed description of defamation and libel and the bill passed with overwhelming support.

At the federal level, there has been very little action on regulation of facts in political advertising. The Honest Ad Act, introduced by Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), Mark Warner (D-Va.), and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), argued that there are strong disincentives for candidates to “disseminate materially false, inflammatory or contradictory messages to the public” through traditional media because the public nature of these outlets allows for “the press, fact-checkers and political opponents” to view and react to the advertisements and that these deterrents do not exist on digital media where targeted advertising is the rule. The act argued, as Warner did in his letter to Zuckerberg, that the norms which regulate traditional media must also be upheld by digital platforms.

The Honest Ad Act specifically seeks to include digital platforms in the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971—an important step in addressing technological advances since the act became law. But the simple inclusion of internet media in the act is not enough to protect voters from dishonest communications because it does not include calls for truth or fact-checking political advertising.

The Brennan Center recently drafted legislation targeting false information in political ads and urged that the “Truth in Advertising” standards that companies must abide by should also apply to electioneering, too. Should Congress target unregulated political advertising, as the Brennan Center suggests, the path forward could be extremely complicated—as evidenced by Washington’s rocky experience.

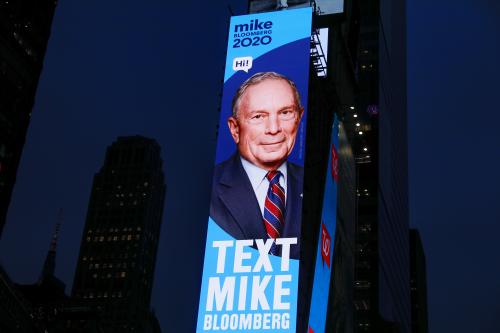

Senator Warner and others have urged digital media to adopt the “norms” that cable networks use in fact-checking political advertisements. However their efforts have not been persuasive enough for these platforms to implement such a process. The 2020 election has already been marked by false advertising campaigns on Facebook and there is no legislation underway at the federal level that would specifically target disinformation in electioneering.

Future regulation must go beyond the Honest Ad Act and follow the path that some states have taken. Writing legislation with specific calls for fact-checking in political advertising will be imperative to protecting citizens and ensuring the integrity of our political campaigns.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Regulating fact from fiction: Disinformation in political advertising

December 20, 2019