See an updated analysis here.

Economic recessions result in widespread pain: an increased likelihood of job loss, longer unemployment spells, business closures, reduced tax revenues, less access to credit, financial stress, and lower growth. When there is a recession, policymakers can employ a range of fiscal and monetary policy tools to temper the depth and duration of the downturn.

Some countercyclical tools do not require policymaker action: Historically, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program) has been a key automatic stabilizer because it has been designed to quickly expand to meet increased need without any intervention. When people lose their jobs or experience a decline in income and become eligible for SNAP, they can quickly enroll in the program and receive and spend benefits. SNAP not only helps to provide a basic need—resources to put food on the table—but it also helps stabilize and stimulate the economy.

In this piece, we analyze how the SNAP cuts that recently passed the House would affect the program’s response to a future recession. The policy changes that most directly affect SNAP’s role in fighting recessions include, for the first time, transferring substantial new costs to states, subjecting older Americans and parents without children under age 7 to time limit work requirements, curtailing states’ ability to request place-based waivers from time limit work requirements when their local economies are struggling and reducing the amount of SNAP benefits that many households receive. The House bill also includes other SNAP cuts that are not as directly related to the program’s ability to respond to economic downturns as these changes.

We find that these changes would undermine SNAP’s role in combatting recessions, penalize workers who have recently lost their jobs or income, and increase food hardship among workers, children, and the elderly. If Congress were to restructure SNAP by ending full federal funding of program benefits, increasing exposure to work requirements that cut off benefits at times when most people who are looking for jobs cannot find them, and making it harder to waive such work requirements when evidence shows that labor markets are weak, the automatic stabilization features of the program would be undercut.

An unprecedented mandate for states to pay for a portion of SNAP benefits would inhibit SNAP’s ability to respond to recessions

SNAP is a particularly efficient way to spend federal money to stabilize and stimulate the economy during a downturn. Economic downturns can be local or regional due to factors such as the decline of a regional economic sector, plant closures, or natural disasters, in addition to nationwide. During downturns, SNAP benefits are spent quickly and increase spending at grocery stores. Consequently, SNAP benefits have a notably high multiplier: The economic benefit per dollar spent on SNAP during a recession is well in excess of a dollar.

In a hypothetical downturn, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has estimated that each additional dollar spent on SNAP benefits causes total economic activity to increase by $1.40 to $1.50. There are no estimates of what would happen if SNAP benefits were cut during a recession, but the magnitudes are plausibly similar: more than a dollar in total economic activity lost for every benefit dollar cut.

The measured impact of increased SNAP benefits varies across recessions depending on the broader economic conditions. During the height of the Great Recession, the economic impact of SNAP increases was quite high: A dollar of SNAP benefits caused between $1.74 and $1.79 in new economic activity. Included in this increase, for every $10,000 in new SNAP benefits in a county, researchers found that one additional job was created in non-metro counties, and 0.4 jobs were created in metro counties. Late in the COVID recession, the American Rescue Plan’s SNAP benefit enhancement caused $1.61 in economic activity for every dollar spent.

For the entirety of its more than 50-year history, SNAP benefits have always been paid by the federal government alone. The House bill changes the structure of SNAP: It mandates that states pay for no less than 5 percent of SNAP benefits starting in FY2028. Based on annual payment error rates, states would be required to pay 15 percent of benefits (if a state’s error rate is equal to or greater than 6 percent but less than 8 percent), 20 percent of benefits (if a state’s error rate is equal or greater than 8 percent but less than 10 percent), or 25 percent of benefits (if a state’s error rate is 10 percent or higher).

The SNAP payment error rate reflects how accurately states make eligibility and benefit determinations: It is not a measure of fraud. The bill redefines what an error is from $57 (the dollar amount is set annually) to “$0.” In doing so, measured error rates will increase because USDA will no longer disregard errors with negligible cost. Currently, when a state has an error rate of 6 percent or above, the state works with USDA on a Corrective Action Plan, and substantial penalties can be levied against states.

The House bill makes it harder for states to invest the resources needed to reduce errors by cutting in half (from 50 percent to 25 percent) the share of state SNAP administrative costs that the federal government covers, and it eliminates some program simplifications, making eligibility and benefit determinations more complex, despite the fact that greater complexity tends to result in more errors.

In providing an estimate of the effect of pushing no less than 5 percent of SNAP benefit costs onto states, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has warned that this policy could lead some states to drop out of the program, reflecting compelling evidence that with nearly all states being required to balance their budget each year, many states would not be able to shoulder the substantial costs of this policy change even under good economic conditions. Moreover, states certainly do not have the flexibility or tools that the federal government does to borrow to cover increased program costs during a recession. This cost shift is on top of other cost shifts in the House bill, most notably Medicaid cuts.

During recessions, the total cost of SNAP benefits rises as more families become eligible for the program due to declining income and/or job loss. Making matters worse, error rates tend to increase during a recession when states have to deal with an influx of new applicants and larger caseloads. Under the House-passed policy, this implies that state payment rates (i.e., the share of benefits that states have to pay) would increase during a recession in addition to an increase in the level of SNAP benefit costs that they have to pay.

Meanwhile, state tax revenues decline along with the decrease in economic activity that characterizes a recession. While federal tax revenues decrease as well, the federal government can borrow to offset the gap that arises due to lower revenues alongside increased costs. In contrast, every state but Vermont is required to balance its budget each year and would be unable to borrow to meet the demands of their increased SNAP costs.

The generalized problem—states are unable to adequately respond to recessions—is well-documented. For example, during recessions, states often reduce spending on programs in their jurisdiction, like education, transportation, and public safety. States are not able to handle Unemployment Insurance expansions. A recent study found that when a state receives federal assistance that allows them to avoid $1.00 in program cuts, at least $1.70 in additional economic activity results.

The proposal to shift benefit costs onto states that just passed the House would result in SNAP being restructured into a program more similar to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). States are required to provide substantial funds for these programs. This structure inhibits countercyclical response. Indeed, in recent recessions, Congress has acted to curtail the economic drag of state belt-tightening by temporarily increasing the federal share of Medicaid and CHIP expenditures to provide more resources to fill state coffers.

It is not unprecedented, although it is quite unusual, for the federal government to change the structure of a basic needs program. Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was a cash entitlement program that provided benefits to all eligible families that applied; in 1996 it was converted to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), a block grant with participation time limits. It is widely recognized that TANF’s structure has rendered it unresponsive to growing need during economic contractions; while SNAP expands during a recession, TANF does not.

If enacted as currently written, this policy would not be in place before FY2028, but it would be in effect permanently starting then. When a state cannot pay for its obligations during a future recession without markedly cutting benefits, SNAP will not expand to meet need; instead, it may contract.

The consequences of restructuring SNAP to mandate that states pay a portion of benefits will not be borne solely by SNAP participants. States that attempt to preserve SNAP benefits may find it necessary to cut education, health, or other programs as a result. Without SNAP serving as an automatic stabilizer, there will be less stimulation of the economy, worsening downturns. Such outcomes occur if SNAP changes from a fully federally funded basic needs program to one in which states are responsible for paying for a portion of benefits, regardless of the exact details of the policy change.

A work-based safety net doesn’t work during a downturn

In a recession, more workers are unemployed and trying to find a job, and employment opportunities are more scarce. Work requirements abbreviate the countercyclicality of SNAP because they condition eligibility on both income and employment.

The House bill increases exposure to time limit work requirements. Time limit work requirements require that participants successfully report that they spent at least 80 hours per month on allowable activities such as work or training. Time spent looking for work does not directly count as an allowable activity. If participants do not meet the requirements, then they are eligible to receive only three months of SNAP benefits in a three-year period unless they come into compliance or live in an area where work requirements are waived. Currently, so-called able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs), defined as people between the ages of 18 and 54 who are not pregnant, veterans, homeless, or youth aged out of foster care, are subject to these work requirements.

The House bill adds two new groups to the time limit work requirement: ABAWDs between the ages of 55 and 64 and able-bodied adults between the ages of 18 and 64 whose youngest dependent child is between the ages of 7 and 17. If the adults are married and coresident, only one is required to meet the work requirement. This would take effect immediately.

Setting aside that the most rigorous research evidence finds that SNAP work requirements do not increase employment, each of these proposals would diminish SNAP as an automatic stabilizer. While we comprehensively explain work requirement evidence and policy in this primer and these proposals, here we elevate evidence that shows that work requirements penalize workers during recessions.

Who is on SNAP depends on economic conditions

When the economy slows and as incomes fall, those who were not previously eligible for means-tested programs become eligible and participation increases. Countercyclicality in SNAP has increased since the early 1980s. During the Great Recession, increased unemployment explained most (two-thirds) of the caseload increase while place-based waivers from the program’s work requirements explained about 10 percent. During the COVID recession, temporarily higher SNAP benefits explained about half of the increase in enrollment, waiving recertifications about 11 percent, and changes in the unemployment rate about 7 percent. While poverty itself is cyclical, recent research finds that countercyclical tax and transfer programs make it less so. These programs do what they were designed to: expanding to offer more help when there is greater need.

One group for whom participation in basic needs programs demonstrably grows during a recession are working-age adults. Figure 1 shows SNAP participation relative to 2007 and affirms that SNAP participation is countercyclical for the groups subject to or under consideration for being subject to time limit work requirements except those over the age of 60. It also shows that enrollment peaks following the onset of a recession for different groups at different times and that recoveries from recessions are delayed (and varied) among this population. For example, participation in SNAP among ABAWDs 18–49 peaked during the Great Recession in 2013, almost four years after the national unemployment rate did, and was still elevated in 2023, three years after the unemployment rate peak during COVID.

Participation in SNAP among parents without young children also rose after the Great Recession, peaking in 2013, and fell during the recovery through 2019 before increasing again in the wake of COVID-19. Countercyclical SNAP participation increases also occur among children, parents of young children, and individuals with disabilities (not shown). For each of these groups, participation increased by more than 50 percent in the years after the Great Recession, fell through the labor market peak in 2019, and increased again following the COVID-induced recession. None of these groups had their SNAP participation decline to 2007 levels, but of course, the population also grew over this time period.

Only older adults do not have a countercyclical pattern of SNAP participation because their eligibility is less tied to employment status changes. Participation in SNAP among those ages 65 or older more than doubled between 2007 and 2019; between 2019 and 2023 it increased even more sharply so that by 2023, participation among this group had increased by 200 percent relative to 2007 (not shown). These increases likely reflect policies to increase SNAP participation among older Americans to reduce food insecurity among seniors, including outreach and application assistance. Between 2007 and 2023, the total U.S. population aged 65 or older increased by 60 percent. Participation among those aged 60 to 64 has followed a similar path to those aged 65 and older. It is worth noting that 53 percent of ABAWDs aged 60 to 64 receive Social Security benefits, likely reflecting high levels of early retirement.

While the number of people participating in SNAP increases and declines with local labor market conditions, most participants in SNAP are elderly, disabled, children, or parents of young children. On average, 75 percent of all SNAP participants belong to one of these groups. Figure 2 below shows SNAP participation over time by group. Those who are not subject to work requirements are in shades of blue. ABAWDs aged 18–54, who are currently subject to work requirements, are shown in green. Groups that would be newly subject to work requirements under the House bill—ABAWDs aged 55–59 and aged 60–64, and parents without young children—are shown in shades of yellow.

Participation in SNAP among working-age adults is both relatively low and more countercyclical. During the Great Recession and the COVID recession, Congress suspended work requirements nationwide. During those periods when the ABAWD work requirement was suspended or work requirement waivers were widely in use, participation in SNAP increased relatively more among those otherwise subject to the time limit. ABAWDs make up between 7 and 10.5 percent of SNAP participants over time. In recent years, ABAWDs between ages 50 and 54 have been added to the time limit work requirement; approximately 2 percent of all SNAP participants fall into this group of older ABAWDs.

The House bill subjects additional SNAP participants to the time limit work requirement: older Americans (55–64). Those aged 55 to 59 represent another 2 percent of SNAP participants. ABAWDs aged 60 to 64 have become an increasing share of SNAP participants, growing from about 2 percent of participants to about 5 percent. In 2023, about 13 percent of older SNAP participants were working, 9 percent were unemployed, and the remainder were not in the labor force. Another group that would be newly subject to work requirement time limits under the House bill are parents whose youngest child is between the ages of 7 and 17. This group made up about 8 percent of SNAP participants in 2023.

Work requirements penalize workers

Eligibility for means-tested programs increases during a contraction because workers lose income or their jobs. USDA studied, and Elizabeth Cox, Chloe N. East, and Isabelle Pula summarized, the circumstances that precipitated SNAP enrollment during the Great Recession (figure 3). This research finds that a full 91 percent of new SNAP recipients experienced a job loss (29 percent) or loss of income (62 percent) before applying for SNAP. Many low-wage workers are not eligible for Unemployment Insurance when they lose their jobs. Low-wage workers apply for and use SNAP as insurance to support them through this hardship. New evidence shows that receiving SNAP improves employment outcomes.

Work requirements penalize the unemployed. While those subject to time limit work requirements have to show that they work or participate in otherwise sanctioned activity for at least 80 hours per month, time spent searching for work does not count towards this requirement unless it is an aspect of an E&T program or a participant meets the general work requirement through receiving Unemployment Insurance. In other words, if a SNAP participant is subject to the time limit work requirement, they will be removed from the program if they cannot find work within three months, and the state does not provide them a slot in an approved E&T program. States generally do not offer anywhere close to enough E&T slots during economic expansions, let alone during contractions.

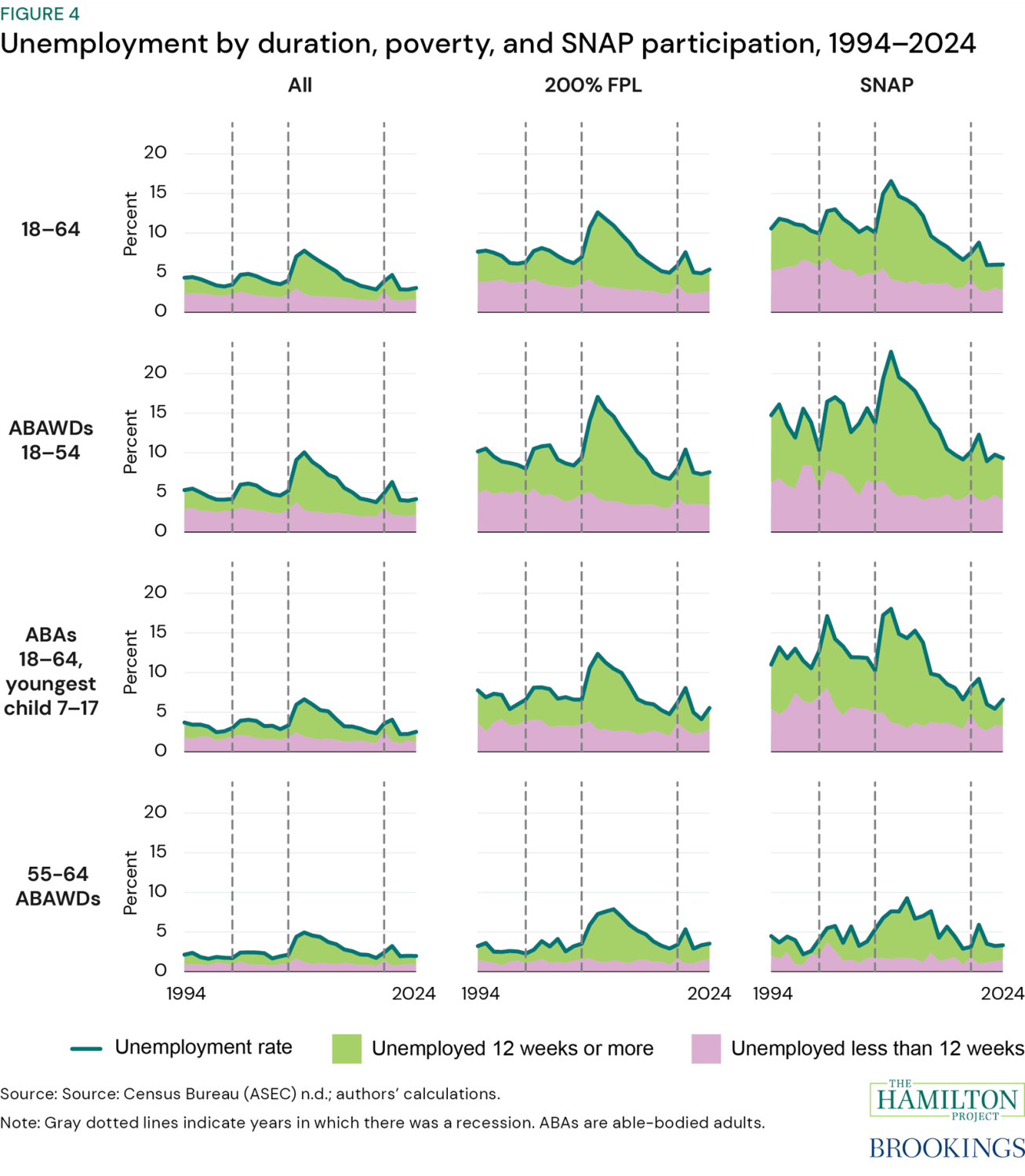

Figure 4 shows that unemployment is quite high among low-income and SNAP participating households and that unemployment durations in excess of three months (lime) are pervasive among these groups, particularly during downturns and slow recoveries. When the national unemployment rate reached its peak (10.0 percent in October 2009) during the Great Recession, that year the unemployment rate among SNAP participants was even higher: 19.3 percent (ABAWD 18–54), 6.8 percent (ABAWD 55–64), and 17.2 percent (18–64, youngest child 7–17), respectively.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of full-time work, part-time work, or unemployment (actively seeking work) in the survey month for SNAP participants who would be subject to the time-limit work requirements under the House bill. During recessions, the share of SNAP participants who are in the labor force increases, and the share of labor force participants who are unemployed also increases; again, participation in SNAP for these groups is countercyclical. Regardless of macroeconomic conditions, the majority of ABAWDs 18–54 and parents of older children are labor force participants. For those who are in this population and out of the labor force, work-limiting disability is quite prevalent.

This figure also shows that the conditions of the low-wage labor market also contribute employment outcomes, not only participants’ desire to work. In 2012, when SNAP participation during the Great Recession business cycle peaked, about half of SNAP participants in each of the work requirement expansion populations who were in the labor force were looking for a job; for ABAWDs 18–54, two-thirds were looking for work. In the most recent year available (2023), a third of SNAP participating parents of older children in the labor force were looking for work, about 41 percent of ABAWDs 55–64 were looking for work, and more than half of ABAWDs 18–54 were looking for work.

Elizabeth Ananat, Anna Gassman-Pines, and Olivia Howard find that even when labor market conditions are improving (as they were in 2022) among low-wage service workers without minor children in the household who meet work requirements on an annual basis (i.e., who work an average of more than 80 hours per month for the year), 42 percent have at least one month where they work less than 80 hours, and 25 percent have at least one month of unemployment.

Proposed SNAP work requirement waiver rules tie states’ hands

When local economic conditions warrant, states can apply to USDA for waivers from time limit work requirements for local labor markets; waivers are a safety valve for turning off time limits. By breaking the connection between SNAP eligibility and work requirements when local labor market conditions are weak, SNAP can provide additional support to states and local economies that have elevated unemployment or have experienced idiosyncratic economic shocks even when the national economy is not itself weak.

As there is no one way to identify the conditions that make it difficult to secure employment, there are several measures of labor-market weakness (“lack of sufficient jobs”) in the current ABAWD work requirements rules that are used to determine whether a local or state area qualifies for a waiver. Such measures currently include having elevated unemployment relative to the national average, defined as having an unemployment rate at least 20 percent higher than the national average over a recent period (commonly called the “20 percent rule”); high unemployment, defined as having a 12-month or 3-month average unemployment rate above 10 percent; a state-wide rule for when Extended Benefits to Unemployment Insurance triggers on; and a handful of other economic criteria that are less commonly used. Waivers can be requested for a wide variety of types of geographic areas, including states as a whole, smaller geographies like Indian Reservations, counties, cities or towns, and state-determined groupings of contiguous labor market areas.

The House bill makes it harder for states to waive work requirements when labor market conditions are poor and reduces the number of individual hardship exemptions that states can issue in a given month. The House bill proposes to radically change waiver criteria: Waivers will only be available to counties or county-equivalents with an unemployment rate above 10 percent. (For Medicaid work requirements in the same bill, the waiver criteria are an unemployment rate above 8 percent or an unemployment rate 50 percent higher than the national average.) Changing the geographies for which a state can apply for waivers to only counties or county-equivalents removes Indian Reservations entirely from the list of eligible areas and ends the flexibilities that states currently have to request a state-wide waiver, waivers for non-counties like towns, and waivers for state-defined labor market areas. These changes would take effect immediately.

Figure 6 shows how quickly these measures of labor market weakness responded to the Great Recession by county. It also shows the period during which Congress suspended work requirements nationwide (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act waiver) and the additional Unemployment Insurance-related waiver that the George W. Bush administration put in place (Emergency Unemployment Compensation). This analysis shows that the 20 percent rule is procyclical, but that this feature allows the rule to waive locations with relatively high unemployment early in a recession. During the depth of this recession, tying waivers to the same rule that extends the duration of Unemployment Insurance benefits (EB) provided the most coverage. The 10 percent unemployment by county rule (orange) was both slow to respond to the onset of a downturn and failed to reach 40 percent of counties.

Changing waiver criteria to only the 10 percent rule undercuts recession responsiveness. Figure 7 applies the work requirement waiver policy in the House bill to the Great Recession, showing how long it took counties to reach 10 percent unemployment after the recession started. An accompanying data interactive allows users to see how this policy change would have affected each state.

Figure 7 and the accompanying state-by-state analysis show that limiting waivers to counties with unemployment above 10 percent severely slows waiver availability during a recession. When the Great Recession started in December 2007, only 76 counties (where 3.0 million people live) were already at 10 percent unemployment. Within the first year, an additional 289 counties (14.9 million people) hit 10 percent unemployment. In years one to two, 1,177 additional counties (131.2 million people); in years 2 to 3, an additional 319 counties (31.5 million people); in years 3 to 4, another 33 counties (1.4 million people). Between the fourth year and the end of the business cycle, 19 additional counties (0.9 million people) reached 10 percent unemployment. And 1,210 counties (116.8 million people) never reached 10 percent unemployment during the Great Recession.

To be clear, 10 percent unemployment is a very high standard. At a national level, 10 percent unemployment was reached in only one month during the Great Recession. About 40 percent of the population lived in a county where, during the Great Recession, county-level unemployment did not reach 10 percent.

Conclusion

As recession probabilities and uncertainty about the direction of the economy increase, the House has passed a bill that would permanently change SNAP. The program provides much-needed relief to families when they fall on hard times. It also serves as a crucial financial stimulus because participants quickly spend benefits in their local economies. The consequence of the proposals in the reconciliation bill is a diminishment of SNAP’s countercyclical capacity: Each of the policy changes to SNAP passed by the House undermine both the ability of the program to alleviate hardship and its contribution to stabilizing demand during a recession. In any event, but certainly if, unlike during past recessions, Congress fails to respond to the next recession, then it is prudent to leave SNAP be.

SNAP could be reformed to be even more effective in responding to recessions. For example, we have proposed that a temporary increase in federally funded SNAP benefits should automatically kick in when the economy contracts, as should a nationwide suspension of SNAP work requirements. Such policies, which are similar to those Congress enacted during the last two recessions, would protect Americans from some of the hardship that comes with a recession, break the relationship between work and program eligibility when there are many fewer jobs available, and stimulate the economy by targeting resources that will be spent quickly by those in need.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank Aviva Aron-Dine, Stacy Dean, Chloe East, Bob Greenstein, and Este Griffith for gracious feedback. Olivia Howard, Eileen Powell, Noadia Steinmetz-Silber, and especially Asha Patt provided superb research assistance. The authors thank Joyce Chen, Jeanine Rees, and Marie Wilken for excellent editorial assistance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).