Five years ago, President Obama spoke at the graduation ceremony at Kalamazoo High School in Michigan—an unusual move for a sitting president. Why Kalamazoo? Because thanks to a generous group of local anonymous donors who created the ‘Kalamazoo Promise’, almost every high school graduate gets a scholarship that pays from two-thirds up to the entire cost of college tuition.

Did it work? For whom? What lessons, if any, can be learned from this program? These are the questions we’ll be addressing in this blog and subsequent contributions from Timothy Ready and Brad Hershbein.

The Kalamazoo Promise

The Promise financing is simple to obtain (students fill out two short forms) and, unlike many other similar programs, there are few strings attached: essentially just being in the school system long enough and graduating high school. The scholarship covers 130 credits of college education (equivalent to a bachelor’s degree) at any 2- or 4- year public institution within Michigan and is worth more to those who have spent the most years in local public schools. Starting in 2015, students can use the scholarship at many in-state liberal arts colleges. The funding is available for 10 years after high school graduation—even if recipients leave college and return—and the only requirement to keep it is that students maintain a college GPA of at least 2.0.

Kalamazoo’s trajectory has turned…

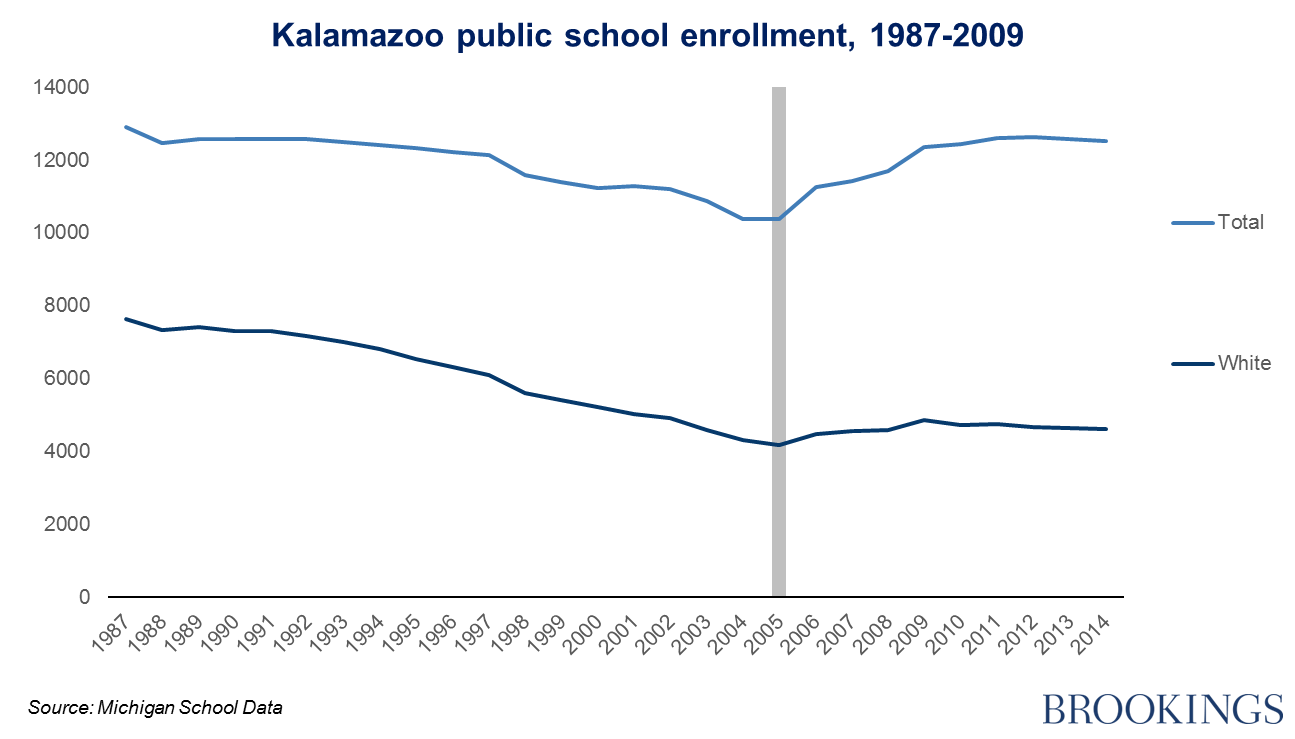

After decades of enrollment decline and white flight—Kalamazoo’s population shrank by 15 percent between 1970 and 2010—more kids are attending the city’s public K-12 schools:

Three years after the Promise was introduced, the chance of passing at least one high school course over the year rose 9 percentage points, and roughly 85 percent of qualifying students had used the scholarship to enter college, according to analyses by Timothy Bartik and Marta Lachowska of the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. The effects were especially large for black students who saw a 13 percentage point increase in the probability of obtaining any high school credit, spent 3 fewer days in suspension, and increased their average GPA by 0.7 points—nearly a letter grade. Ten years into the program, 90 percent of Kalamazoo high school seniors are enrolling in college.

Where Kalamazoo leads…

More than 35 cities, from Denver and Pittsburgh to Buffalo and Pensacola, have since adopted their own versions of “the Promise.” These vary greatly in scope and design. Some have minimum GPA requirements. Others target only low-income students, or only provide funding after students apply for other scholarships and grants.

But it is not all good news. Making college free (or close to it) does not mean everybody will make it though college. Of those graduating Kalamazoo high schools in 2006, 41 percent have obtained some form of post-secondary credential; this is above the national average for 25-29 year-olds (about 37 percent) but still short of the goals of education advocates. White Kalamazoo students still have college completion rates twice as high as their black peers (54 versus 26 percent). These rates are higher than they were before the Promise was introduced in Kalamazoo, but how much of these gains can be attributed to the program itself? And what other factors may still be holding students back? More on the Kalamazoo Promise from Tim Ready tomorrow.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Promises, promises: What can we learn about education from Kalamazoo?

June 23, 2015