This viewpoint is part of Chapter 3 of Foresight Africa 2026, a report on how Africa can navigate the challenges of 2026 and chart a path toward inclusive, resilient, and self-determined growth. Read the full chapter on Africa’s industry-led growth.

How can African nations rethink their energy needs for industrial progress and economic prosperity without further spiraling up their levels of gas emissions?

In a world increasingly shaped by economic volatility and environmental challenges, the issue of industrialization in Africa presents both great opportunity and great risk. Reversing the continent’s premature deindustrialization1 offers the chance for large-scale job creation—an urgent necessity given the region’s demographic bulge, weak economic outcomes, and rising poverty. At the same time, reducing global gas emissions is a necessary requirement for mitigating climate change. We therefore are facing a reality in which decarbonization is shaping investment patterns while significantly reducing opportunities for developing countries to tap their fossil fuel resources. Against this backdrop, how can African nations rethink their energy needs for industrial progress and economic prosperity without further spiraling up their levels of gas emissions?

First and foremost, we know that access to affordable and reliable energy is a key binding constraint for long-term, industry-led growth, and that nearly 600 million people2 in sub-Saharan Africa still do not have access to electricity (over 80% of the global electricity deficit).3 With the African population expected to surpass 2.5 billion by 2050,4 the demand for energy and food is expected to continue to soar.

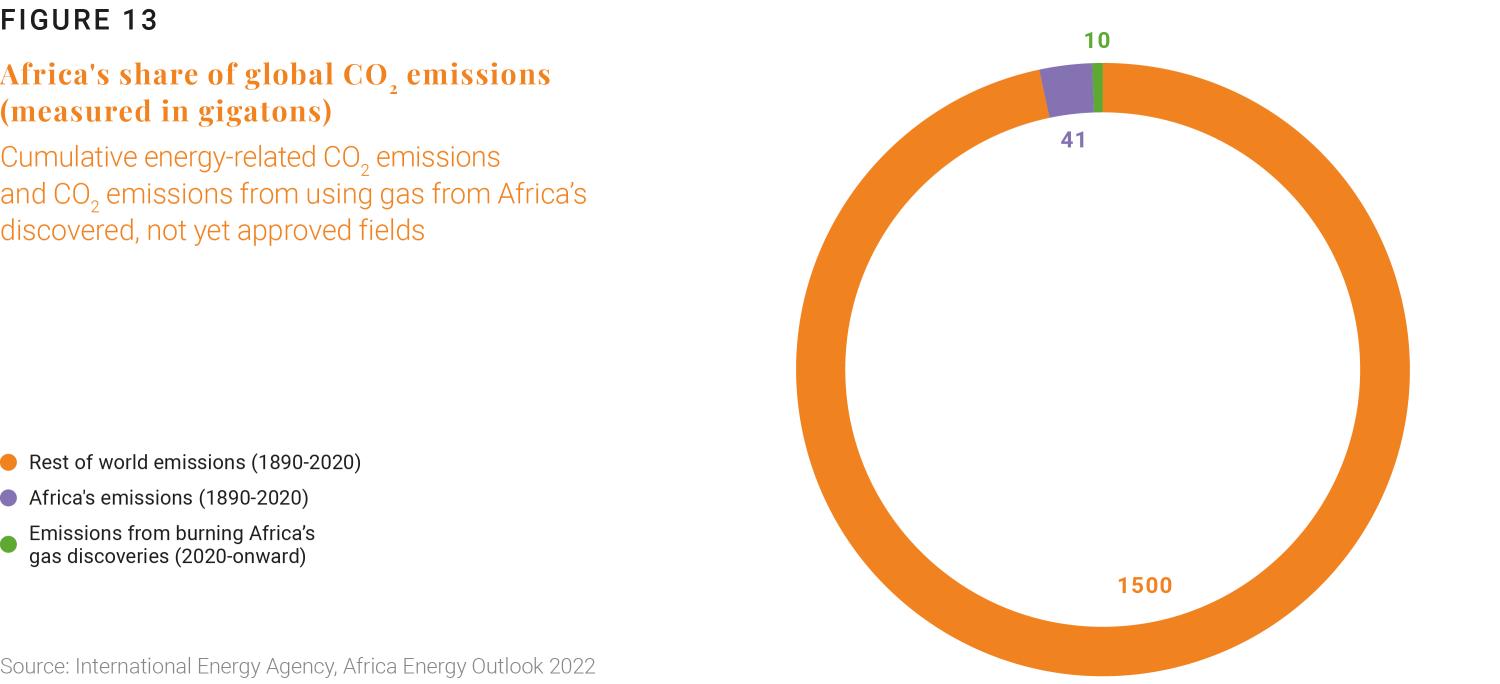

On the other hand, the continent faces a disproportionate burden to decarbonize, even though it contributes a tiny proportion (less than 4%) of global greenhouse gas emissions.5 The goal of net-zero is a global one and does not necessarily have to be achieved by each country or on the same timeline.

Accordingly, calls for Africa to accelerate its decarbonization efforts are in effect penalizing the region for the historical emissions of much more advanced countries.

Crucially, most of the net-zero modeling for Africa is based on projections that do not align with the region’s own development ambitions or aspirations for industry-led growth.6 Even for the few models that include growth or poverty metrics, assumptions for future energy consumption are extremely modest. According to a 2023 Energy for Growth Hub paper, the most optimistic forecast for sub-Saharan Africa’s per-capita electricity consumption is 1500 kWh by 2050—less than half the global average in 2017 and far below U.S. consumption levels (12,573 kWh).7 These projections, which inform policy as well as investment and financing decisions, are inconsistent with Africa’s rapidly growing population, its accelerated regional integration efforts, and its desire to industrialize. They could lock Africa into a perpetual cycle of low energy access.

The dilemma the continent therefore faces is meeting its growing energy needs to spur development while avoiding the same dependence pattern on fossil fuels that characterized the development model of advanced countries. This is further compounded by the rising need to adapt to the staggering effects of climate change on its economies. Indeed, some estimates suggest that Africa could see a decrease of up to 30% of its GDP by 2050 due to climate change alone.8

Addressing this dilemma and finding the right balance between energy access and climate sustainability should depend on a diversified energy mix—where a balanced mix of fossil fuel, natural gas, and renewables become Africa’s bridge toward a cleaner and more stable energy future. As an example, some resource-rich African countries (for instance Burkina Faso) possess sizeable, low-cost reserves of fossil fuel and yet face low renewable energy readiness due to high costs of capital, limited access to finance, or complex policy challenges such as the high political-economy tradeoffs associated with transition (e.g. compensation of firms and workers dependant on non-renewables). For these countries, the pathway that optimizes development outcomes such as jobs, value addition, and energy access should involve fossil fuels in the short term.9

Other African countries are at the opposite end of the spectrum: They possess little/ no fossil fuel reserves, yet their renewable potential is immense. For such countries, scaling low-cost renewable energy is favorable both in the short and long term. The Sahel region, for example, receives more than 2,000 kilowatt-hours per square meter of solar radiation each year.10 Other countries have high capacity for geothermal and hydroelectric power.11 Together, these resources could sustain new industrial zones powered by hybrid systems—where gas provides reliability and renewables drive long-term growth. Morocco’s Noor solar complex,12 Ethiopia’s hydroelectric expansion,13 and Kenya’s geothermal projects are cases in point. In fact, about 90% of Kenya’s currently generated electricity comes from renewable sources.14

Gas, often described as a “transition fuel,” emits less carbon than coal or oil and already holds a central place in several national strategies. The continent now holds around 7% of the world’s known natural gas reserves,15 from Senegal and Mauritania’s Grand Tortue Ahmeyim field to Mozambique’s Rovuma basin and Egypt’s vast Zohr deposits—these discoveries promise not only greater energy autonomy, but also new revenue streams to finance a green transition.

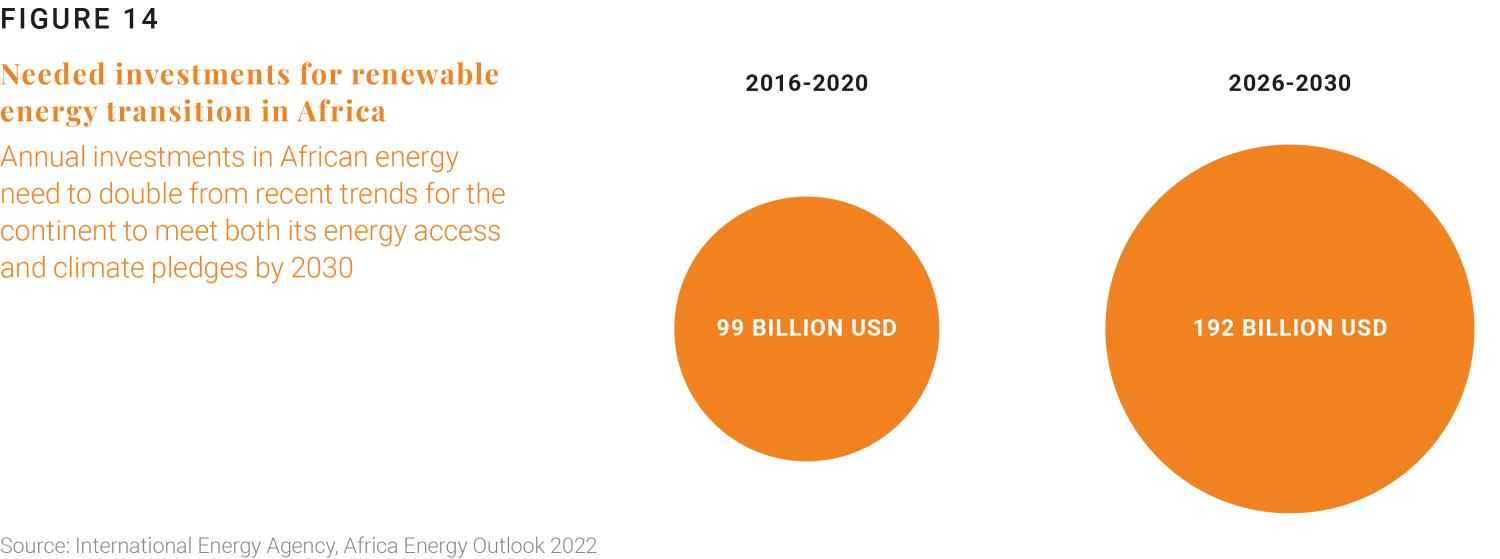

To diversify its production base, gain international market shares, create productive jobs, and reduce poverty, the continent will also need to tap the huge opportunities emerging from technological progress and a fast-changing energy system. Solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, and smart grids are all becoming increasingly important aspects of industrial energy sourcing. Yet without adequate financing, these factors remain inaccessible.

In summary, Africa must prioritize meeting its immediate and present-day energy demands through available resources (including fossil fuels), rather than pursuing a one-size fits all, “leapfrogging” scenario that current economic realities cannot sustain. Africa’s natural gas reserves, over 620 trillion lcubic feet16 across Grand Tortue Ahmeyim, Rovuma basin, and Zohr fields, offer immediate, affordable baseload capacity that industrialization demands. Moreover, short-term fossil fuel development offers Africa the opportunity to support economic growth and development and in turn bolster domestic revenue. With a commitment to reinvest part of these revenues in renewable technology and energy, Africa can accelerate a balanced green transition that also allows for development.

-

Footnotes

- Rodrik, D. (2016). Premature deindustrialization. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(1), 1–33.

- Ramstein, C., & Hallegatte, S. (2025, 21 mars). Connecting 300 million people to electricity and building a resilient future in Africa. World Bank Blogs.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Electricity access continues to improve in 2024 – after first global setback in decades. IEA Commentary.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022. New York: United Nations.

- African Development Bank. (2024). Focus on Africa – COP29.

- Yacob Mulugetta et al., “Africa Needs Context-Relevant Evidence to Shape Its Clean Energy Future,” Nature Energy 7, no. 11 (November 1, 2022): 1015–22.

- Moussa P Blimpo et al., “Climate Change and Economic Development in Africa: A Systematic Review of Energy Transition Modeling Research,” Energy Policy 187 (April 1, 2024): 114044–44.

- Marshall Burke et al., “Global Non-Linear Effect of Temperature on Economic Production,” Nature 527, no. 7577 (2015): 235–39.

- Yacob Mulugetta et al., “Africa Needs Context-Relevant Evidence to Shape Its Clean Energy Future,” Nature Energy 7, no. 11 (November 1, 2022): 1015–22.

- World Bank Group, ESMAP. (2024). Global Solar Atlas.

- “Picking up Steam: Africa Will Overtake Europe in Geothermal Capacity by 2030, $35 Billion Investments by 2050,” Rystad Energy, November 2023; “Hydropower in Africa,” International Hydropower Association, n.d.

- Thomas Finighan, “Morocco’s Noor Solar Project: Redefining Renewable Growth,” The Borgen Project, August 6, 2025.

- Saleem H. Ali, “Ethiopia’s Hydropower Success Exemplifies ‘Convergent Governance,’” Forbes, October 7, 2025

- Climate Investment Funds. (2024, 5 septembre). Project Spotlight: In the final stretch to 100 % clean power, Kenya leads, learns, and clears a few hurdles. CIF News.

- BP. (2021). Statistical Review of World Energy 2021 (70th edition). London: BP p.l.c

- BP (2023). Statistical Review of World Energy 2023. London: BP plc. “Natural gas: Proved reserves by region”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Powering Africa’s industries: Should the region leapfrog the use of fossil fuels?

February 6, 2026