Executive Summary

Executive Summary

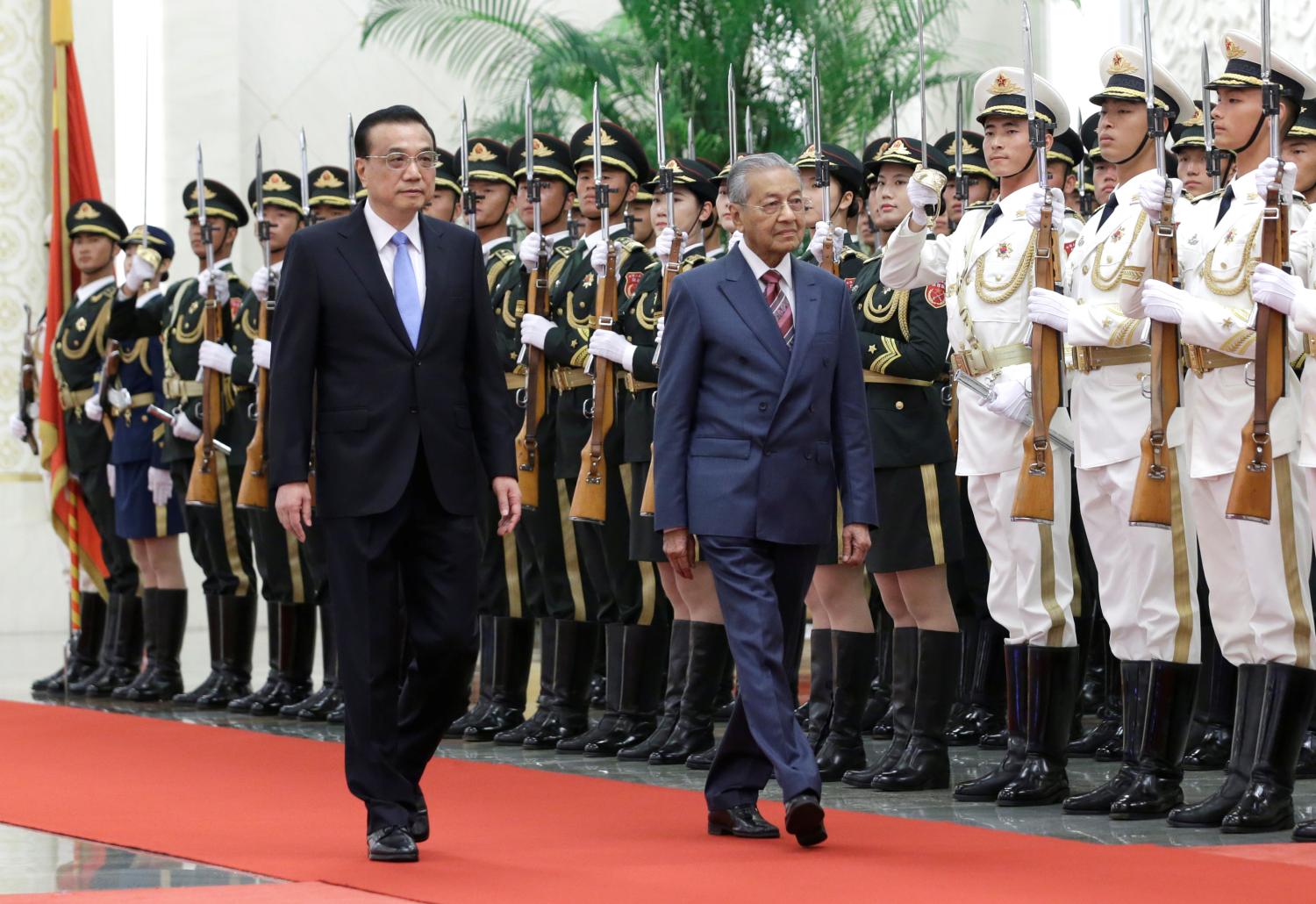

This paper explores how growing geopolitical competition in Asia, increasingly defined by Sino-U.S. rivalry, is affecting governance trends in Southeast Asian countries. The paper begins by describing the geopolitical context itself—especially China’s rising influence and related policy initiatives in the region, as well as changes in U.S. policy toward Southeast Asia under the Trump administration. Then the paper examines how this competition is affecting two states in Southeast Asia representing different population sizes and regime types: Cambodia (small and increasingly autocratic) and Myanmar

(medium-sized and struggling with democratic transition and consolidation). Finally, the paper concludes by assessing the relative weight of these external drivers on domestic governance trends in the region, as compared to long-present domestic

currents within the countries themselves.

Analysis of escalating Sino-U.S. rivalry has focused largely on the security realm and divergent efforts to define the broader regional order, but this great power competition may also be impacting political trends in individual Southeast Asian countries. Despite its official policy of non-interference, China is becoming more involved in the domestic affairs of Southeast Asian countries and is presenting itself as a “new option” for other countries wanting to speed up their development. These efforts appear to be reinforcing or encouraging authoritarian trends (as in Cambodia) and inhibiting democratic consolidation (as in Myanmar), but aren’t necessarily causing other countries to emulate the Chinese model in

particular. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has labeled China a strategic competitor and warns countries in the region that Beijing is using economic inducements and influence operations to advance its political and security agenda. At the same time, the administration has downgraded the pro-democratic posture of the United States and no longer presents America as a beacon of democratic governance, in Asia or elsewhere.

Yet, irrespective of these trends in Chinese and American foreign policy, we see domestic drivers in Southeast Asian countries fueling a democratic resurgence in Malaysia and continued democratic practice and consolidation in Indonesia. At the same time, deeply rooted internal drivers are helping to move things in the opposite direction in the countries discussed in this paper. For instance, the political role of the Burmese military has been institutionalized over many decades and probably exceeds that of the Indonesian military under Suharto, which took many years to unwind. It is therefore critical to keep these internal drivers in mind when considering the impact of U.S.-China rivalry on domestic governance trends in Southeast Asia, or the likely effects of U.S. foreign policy initiatives more specifically.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).