Not everyone knows what an Inspector General (IG) does, but surely Americans of all ideologies can get behind their stated mission: to improve the integrity, efficiency, and effectiveness of government. The 72 IGs throughout the federal government oversee vastly different agencies, but each carries out similar functions, including conducting audits of government programs, investigating fraud both within and outside agencies, reviewing contract, personnel, and management practices, and guarding against waste, fraud, and abuse in all activities of the agency they oversee.

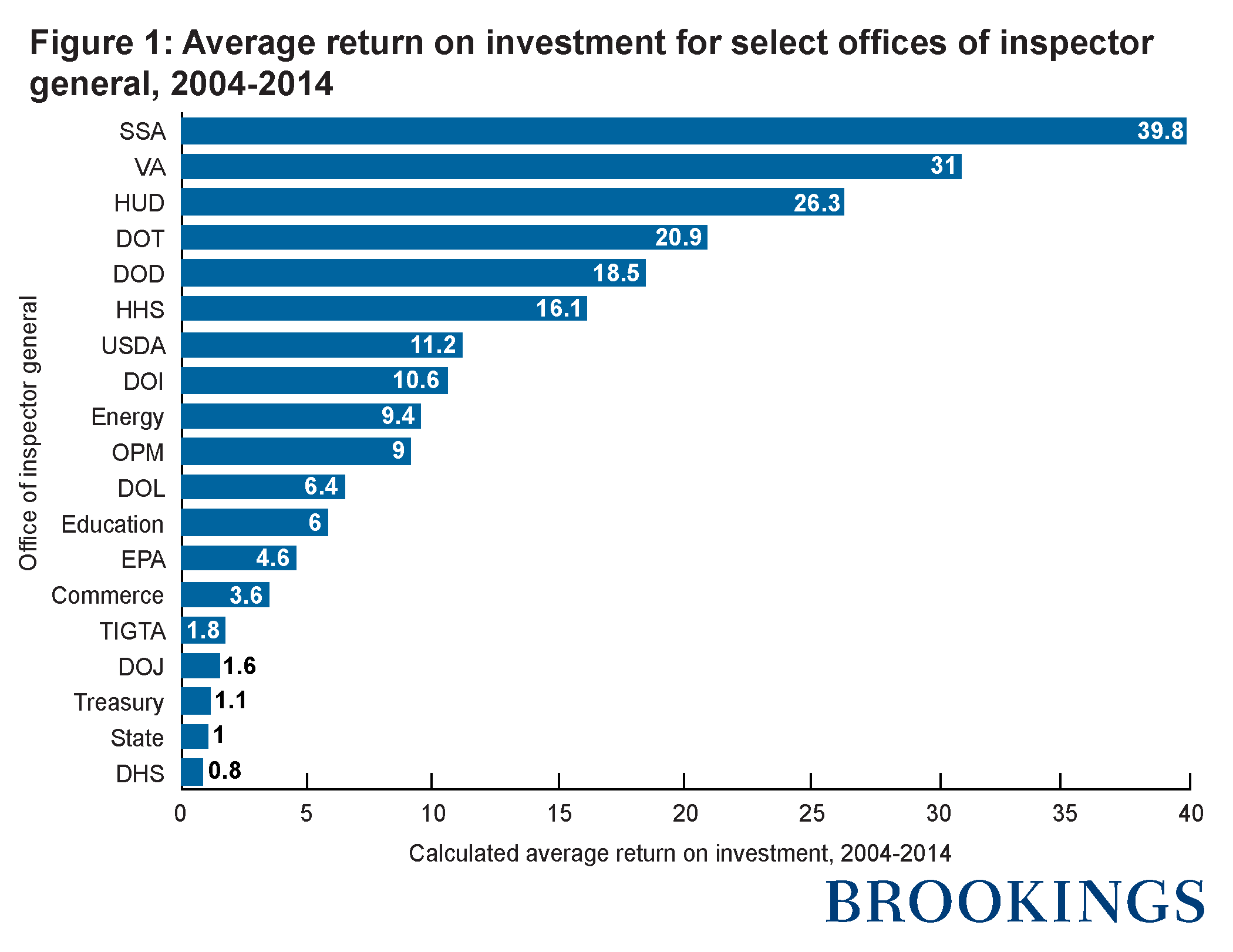

The impacts of IG activities are substantial and diverse, but a great deal of IGs’ work involves fund recovery—one of the ways they improve efficiency of government programs. Because of this, John Hudak and I developed a simple measurement of IG effectiveness: return on investment (ROI). ROI is measured by dividing the total funds an IG brings back to the government in a year by the operating budget of the IG that year.

We found that of the IGs we studied (those at cabinet-level, and other large agencies’ IGs), most had a positive return on investment—in some cases greater than 20 to one.

Despite being an effective measure of effectiveness, ROI does not reflect all IG activities or benefits. The non-monetary benefits that IGs bring to government are crucial and substantial—they take the form of improving operations, safety, preventing discrimination and promoting fair hiring practices, and much, much more. These activities are difficult to quantify across different contexts, and are therefore not reflected in ROI (for a more detailed discussion of the metric, see our earlier paper.)Because these activities are difficult to quantify, it’s likely that our measure of ROI probably vastly understates the positive impact of IGs on governance.

Unfortunately, though, not all IGs are able to do their jobs as well as we’d hope. Recent accounts suggest that agency actors do not always cooperate with IG investigations—either intentionally, or through a culture of stonewalling and lack of communication. But rather than rely on anecdotes, we decided to test the proposition that political influence impedes IG performance. Spoiler alert; it does.

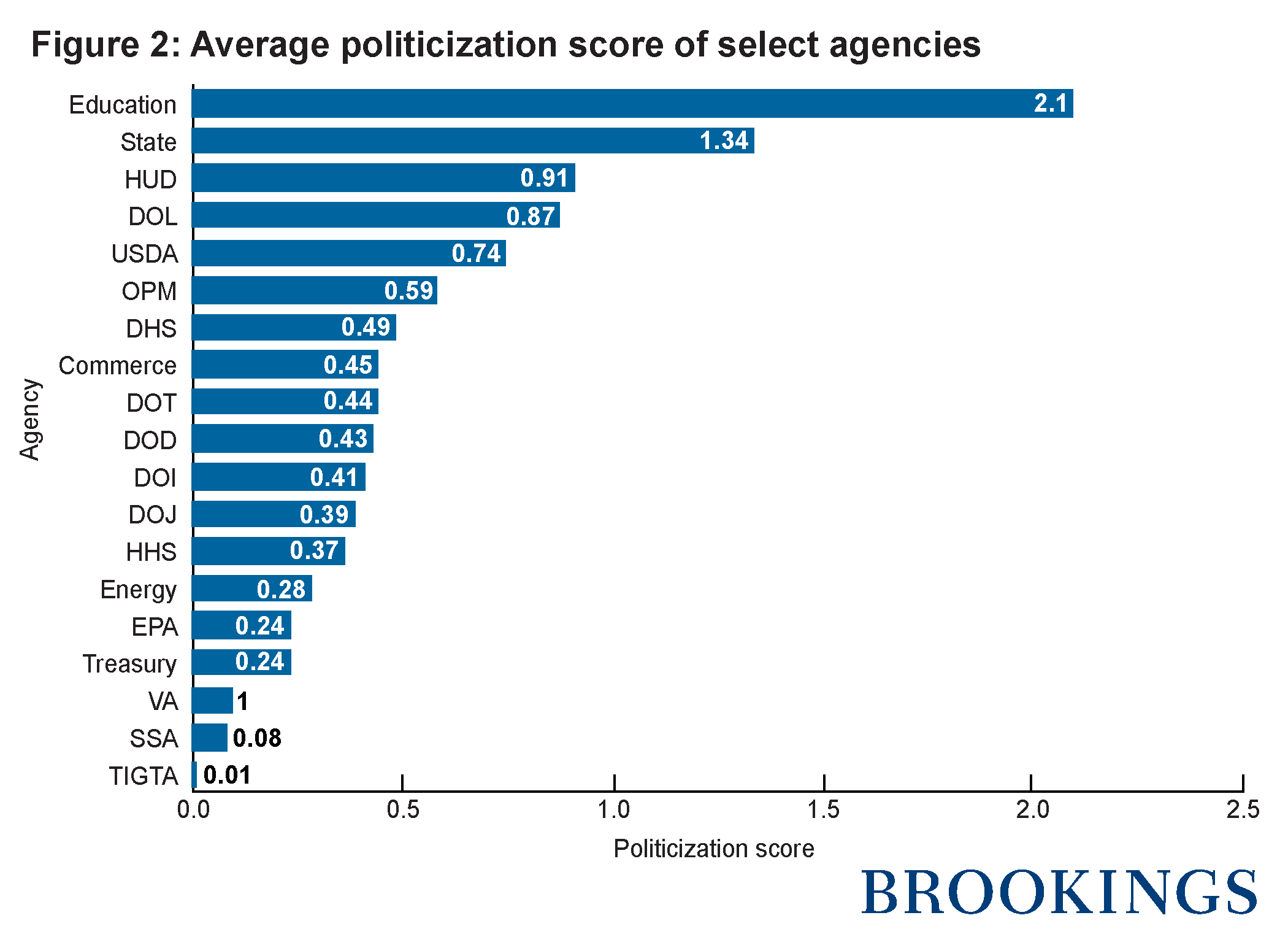

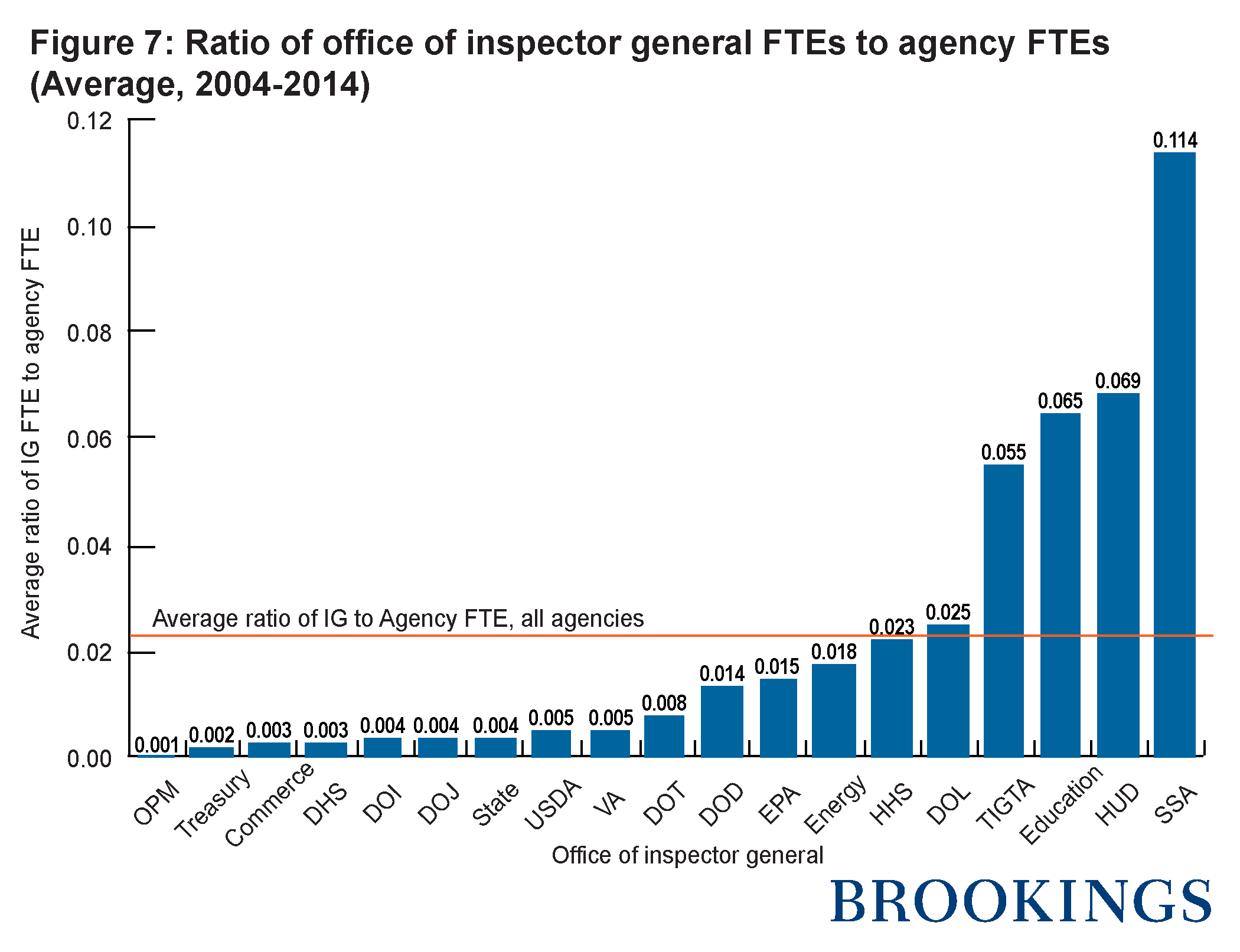

We used three measures to quantify the political influence present in any given federal agency—an overall politicization score, the number of political appointees in the agency, and the number of senate-confirmed appointees in the agency. We tested the impact of each on the ROI of the associated inspector general each year. We found that, while each measure of politicization was associated with decreased IG ROI, the level of Senate-confirmed appointees had the strongest negative effect. Furthermore, we found that negative effects of politicization were most pronounced in IG offices that were relatively understaffed.

For example, the Department of Education topped the list with a politicization score of 2.1. In addition, the Department of Education IG had average staff of only 279 (well below the average of 532). Based on our analysis, we expect this IG would have been particularly negatively impacted by the politicization of the agency. The data bear this out—the Department of Education IG had an average ROI of only 6:1, compared with an average of 13:1 across IGs.

On the other hand, the Social Security Administration and Veterans Administration were among the least politicized, and have the two highest ROIs.

Policymakers would be wise to heed a few lessons from these findings. First, the relative staff level of the Inspector General makes a difference into how impervious to political influence that office is. IGs currently vary wildly in size. Raising the IG staff relative to the agency staff would be a simple mechanism to reduce the power of politicization and improve government.

Not surprisingly, in times of fiscal austerity, IG budgets get cut along with everyone else’s. Given the importance of IGs, and the positive effect they have on the federal government’s bottom line, highlighting ROI in the appropriations process may encourage Congress to keep IG funding at an appropriate level. In addition, creating an IG integrity fund, where a small percentage of IG recoveries are rolled into an account for future investigations, may help IGs smooth the bumps in the appropriations road.

Furthermore, Congress has the power to decide which positions in a commission, department, or agency should be Senate-confirmed. As our findings in the paper illustrate, Congress should avoid concentrating a high number of Senate-confirmed appointees, as doing so can have the adverse effect of reducing IG effectiveness, and therefore allowing waste, fraud, and abuse to continue in the federal government.

Ultimately, if Congress is serious about saving taxpayer dollars, protecting the integrity of government operations, and reducing fraud and abuse in the executive branch, protecting IGs from political influence would be a good first step.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Political appointees harm the integrity and efficiency of government

April 13, 2016