The No Surprises Act (NSA) created a final-offer arbitration process called the independent dispute resolution (IDR) process to settle disagreements about what insurers must pay providers for certain out-of-network services. On June 13, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released a second tranche of detailed data on outcomes under the IDR process. This tranche encompassed disputes resolved during the third and fourth quarters of 2023. CMS released data for the first half of 2023 earlier this year.

This analysis uses the new data to update our prior analysis of IDR outcomes, which examined disputes resolved in the first half of 2023, to examine the second half of 2023. In doing so, we largely follow the methods we used previously, with some exceptions described in the appendix, and we refer readers to our prior analysis for a full description of our methods. In brief, however, we examine disputes involving three broad categories of professional services—emergency care, imaging, and neonatal/pediatric critical care—and examine the same 49 service codes falling within those three categories that we examined previously. These services accounted for 72% of the claim line items adjudicated in IDR during the second half of 2023, similar to the share they accounted for during the first half of the year.

Following our prior analysis, we express the prices emerging from IDR as a multiple of the prices Medicare would pay for the same services. We do so for three reasons. First, this approach offers readers a familiar unit of measurement, as provider-insurer contracts for physician services commonly specify prices as a multiple of Medicare’s, and researchers commonly report estimates in this form. Second, it offers a simple and tractable way to compare the prices emerging from IDR to pre-NSA prices. Namely, we compare our estimates to previously published Medicare ratios for similar (though not identical) collections of services, which we adjust to reflect changes in the overall level of the prices paid by commercial insurers relative to Medicare over time. This approach takes advantage of the fact that related services tend to be priced at similar Medicare ratios, which likely reflects the role that Medicare’s prices often play in private contracts. Third, the comparison to Medicare may be of direct policy interest, as setting out-of-network prices as a multiple of Medicare’s would be an administratively simpler alternative to the current IDR process.

Our findings for the second half of 2023 are similar, but not identical, to those for the first half the year:

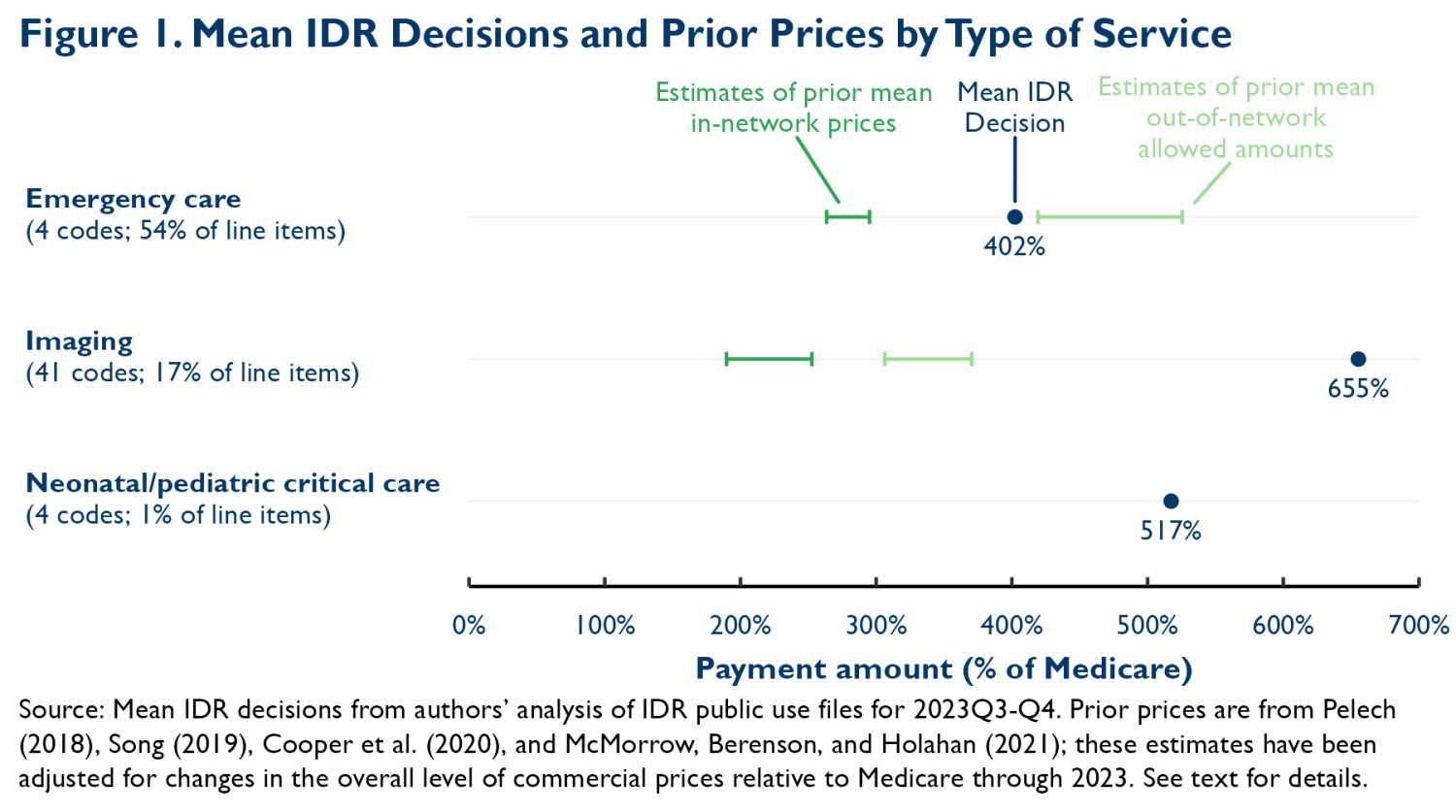

- The mean prices emerging from IDR were higher than the mean in-network prices paid before the NSA—and to a greater degree than in the first half of 2023.1 For emergency services, the prices emerging from IDR during the second half of 2023 averaged 4.0 times what Medicare would pay; for comparison, adjusted estimates of pre-NSA mean in-network prices for similar services range from 2.6 to 3.0 times Medicare. The discrepancy was even larger for imaging services, where prices emerging from IDR during this period averaged 6.6 times Medicare, whereas adjusted estimates of pre-NSA mean in-network prices for similar services ranged from 1.9 to 2.5 times Medicare. The prices emerging from IDR were closer to pre-NSA out-of-network mean allowed amounts, although for imaging services, the prices emerging from IDR greatly exceeded even those prices. For all three types of services, our estimates for the second half of 2023 are higher than the estimates we previously reported for the first half of 2023, with imaging services seeing a particularly large increase, from 5.0 to 6.6 times Medicare.2

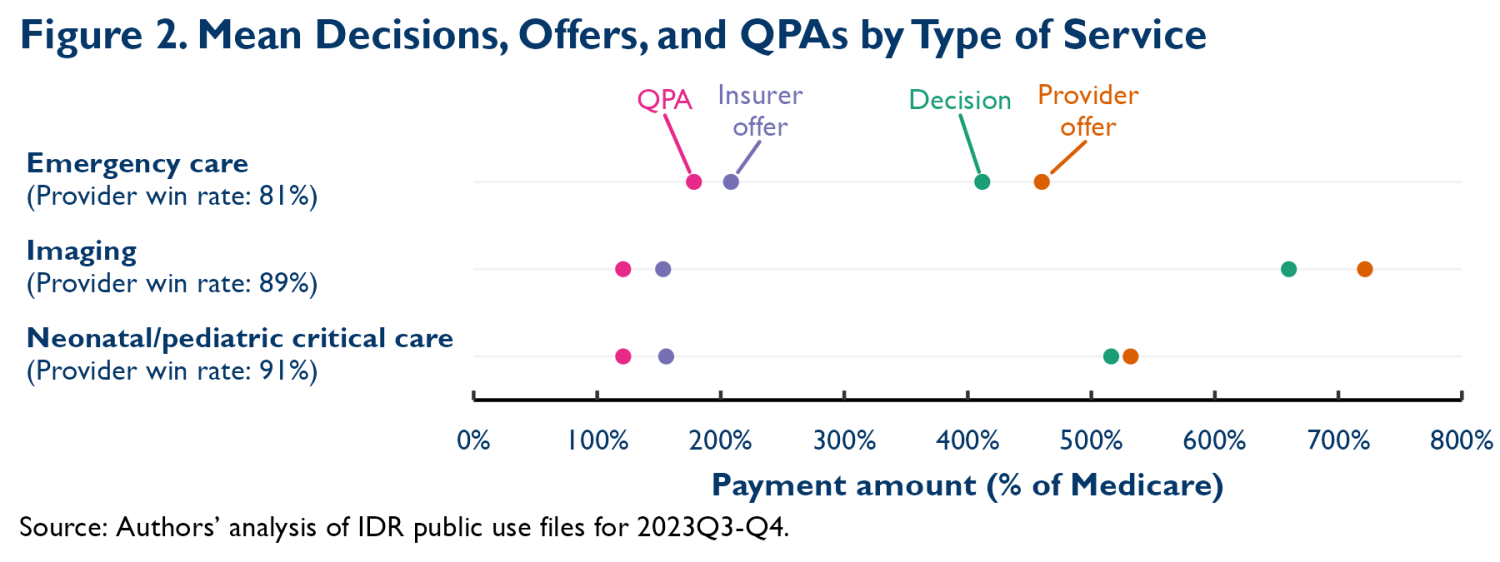

- Insurers’ offers were, on average, slightly above the qualifying payment amount (QPA), the median of the insurer’s contracted rates for the relevant service in 2019, adjusted for inflation. Providers submitted much higher offers, on average, and prevailed at least four-fifths of the time.3 This pattern of offers and decisions is qualitatively similar to what we observed for the first half of 2023; IDR decisions were nevertheless higher in quantitative terms because provider offers, provider win rates and, in some cases, insurer offers were higher. Notably, for both emergency care and imaging services, our estimates of mean QPAs are more than 30% below the adjusted estimates of pre-NSA mean in-network prices presented in Figure 1. That finding echoes what we found in our prior analysis. As we discussed then, this differential could reflect the fact that the QPA is a contract-weighted median (rather than a volume-weighted mean), insurer failures to comply with the rules governing calculation of the QPA, patterns of insurer and provider behavior that cause cases with low QPAs to be more likely to end up in IDR, or some mixture of all three.4

These estimates offer a picture of how IDR has operated to date, but, as we noted previously, they leave at least two important questions unanswered. The first is how arbitrators are reaching decisions. The answer to this question may help inform ongoing debates about what, if any, guidance the federal government should give arbitrators and shed light on why the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) prediction that IDR decisions would hew close to the QPA has not been borne out.

A second key question is what these results portend for the average prices of the affected services and, in turn, insurance premiums. The answer continues to depend on multiple factors, including: whether the IDR outcomes observed so far are representative of what typical provider-insurer pairs would see in IDR; how the parties’ behavior and arbitrators’ decisionmaking evolve in the future; and how IDR outcomes will affect negotiations over in-network prices, all of which remain uncertain. Nevertheless, given that IDR decisions have remained well above prior in-network prices and comparable to or higher than prior out-of-network prices, we continue to see little chance that the law will meaningfully reduce prices and premiums, as CBO had predicted at enactment, and see a realistic possibility that the law will actually raise prices and premiums, in contrast to both CBO’s predictions and the stated goals of the law’s drafters.

Appendix 1: Methodological Details

This analysis uses the same methodology as our prior analysis, with some minor exceptions.

Modified procedure for selecting CPT/HCPCS codes

To maximize comparability between our new estimates and our prior estimates, we analyzed the same 49 CPT/HCPCS codes as in our prior analysis rather than selecting codes using the same criteria we used previously. Of these 49 codes, 9 codes would not have satisfied the selection criteria used in the prior analysis, all because they failed to satisfy the criterion of accounting for at least 200 line items. Applying the selection criteria used in the prior analysis in the new data would also have selected 1 additional code that was not included in the prior analysis.

Modified distributional “trimming” procedure

A limitation of the IDR public use files released for the first half of 2023 was that the file that reports payment amounts (the “payment file”) includes limited information about each line item. Thus, we could not directly exclude two types of line items that were outside the scope of our analysis: (1) line items pertaining to facility, rather than professional, services; and (2) line items that are part of bundled disputes that include multiple services from a single episode of care. Instead, we used the file that did provide information on these characteristics (the “characteristics file”) to estimate the share of the line items for each service code that fell in one of these categories and then excluded the corresponding share of line items from the top of the distribution of payment amounts when analyzing the payment file.

We modified this procedure in a few ways for this analysis:

- The public use files released for the second half of 2023 directly identify line items that are part of bundled disputes in the payment file. Thus, we now directly exclude those line items from our analysis rather than using the indirect trimming procedure described above.

- In our prior analysis, the main way that we identified line items pertaining to professional services in the characteristics file was to match the national provider identifier (NPI) reported for the line item to the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES). We assigned professional status to a line item if the primary taxonomy code for that NPI indicated that it was an “individual” provider. While manually inspecting data for the second half of 2023, we identified some NPIs with “individual” primary taxonomy codes that we suspect are being used to bill for facility services delivered by freestanding emergency departments (because a separate provider that appears to be the physician group associated with these facilities also appears in the data). For line items associated with these providers, we override the NPPES match and assign them facility status.5 This causes us to assign facility status to an additional 2% of the line items we analyze.

This exclusion has a modest, but not trivial, effect on our estimates. The largest effect is on the estimate of the mean Medicare ratio for imaging services reported in Figure 1, which is 7% lower than it would be without this adjustment. The effects on the other estimates in Figure 1, as well as on the medians reported in Appendix Figure A1 are all 2% or less. We note that excluding these providers would have had a smaller effect on the estimates we reported for the first half of 2023, as these providers accounted for a somewhat smaller share of line items in those data.

- When calculating the “trimming” shares in the characteristics file, we would ideally limit the sample only to those line items that report valid payment amounts in the payment file. In the files released for the first half of 2023, we had to use various indirect indicators to identify line items that would likely have missing values in the payment files. The new version of the characteristics file identifies which line items have missing payment amounts more consistently, so we can directly exclude those line items when calculating the trimming shares. As a result, for analyses that examine all line items with a valid IDR decision amount (i.e., those reported in Figure 1), the characteristics file sample is now only 8% larger than the payment file sample, compared to 9% in the prior analysis. For analyses that involve all payment amounts (i.e., those reported in Figure 2), the difference in sample size is also 8%, compared to 16% in the prior analysis. The remaining difference primarily reflects line items for which payment amounts are suppressed in the payment file due to small cell sizes, which we remain unable to identify in the characteristics file.

Adjustments to estimates of pre-NSA prices

As in our prior analysis, we compare the prices emerging from IDR to previously published estimates of pre-NSA Medicare ratios for similar services (see Figure 1). In our prior analysis, we presented the estimated Medicare ratios without adjustment. However, the prices that commercial insurers pay for professional services have risen somewhat more quickly than Medicare’s prices since the years examined in these studies. Adjusting for these changes may better approximate the Medicare ratios that would have arisen in a counterfactual world without the NSA, the comparison of primary interest here.

To make such an adjustment, we relied on estimates of average commercial prices for physician services relative to Medicare published annually by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). MedPAC’s estimates only extend through 2022, so we used the payer-specific Producer Price Indices for physician services published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics to project MedPAC’s 2022 estimate forward to 2023. We then multiplied each pre-NSA estimate by the ratio of the (projected) MedPAC estimate for 2023 to the MedPAC estimate for the year of the data used to produce the pre-NSA estimate.

The resulting Medicare ratios are presented in Figure 1. These estimates are somewhat higher than the unadjusted estimates we used previously. For emergency care, the adjusted in-network ratios range from 2.6 to 3.0, whereas the unadjusted ratios ranged from 2.5 to 2.6; for out-of-network services, the adjusted range is 4.2 to 5.3, compared to the unadjusted range of 3.9 to 4.7. For imaging services, the adjusted in-network ratios range from 1.9 to 2.5, whereas the unadjusted ratios ranged from 1.8 to 2.4; for out-of-network services, the adjusted range is 3.1 to 3.7, compared to the unadjusted range of 2.9 to 3.3.

We note that even these adjusted estimates of pre-NSA Medicare ratios are an imperfect guide to the prices that would have prevailed in 2023 in a counterfactual world without the NSA, as they do not account for changes over time that are specific to the services that we study here. For example, they do not account for changes in the relative prices Medicare sets for different services (although the fact that changes in relative prices in Medicare tend to spur commensurate changes in relative prices in the commercial market may limit the degree to which this is a concern). Similarly, they do not account for changes in market conditions or provider and insurer negotiating tactics specific to these services that may have affected commercial prices. The direction of any bias is unclear, but we doubt that accounting for these factors would meaningfully alter any of the qualitative conclusions we reach here.

Appendix 2: Supplemental Figures

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

We thank Richard Frank for helpful comments, Vani Agarwal and Chloe Zilkha for excellent research assistance, and Chris Miller for assistance with web posting. All errors are our own. This work was supported by a grant from Arnold Ventures.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

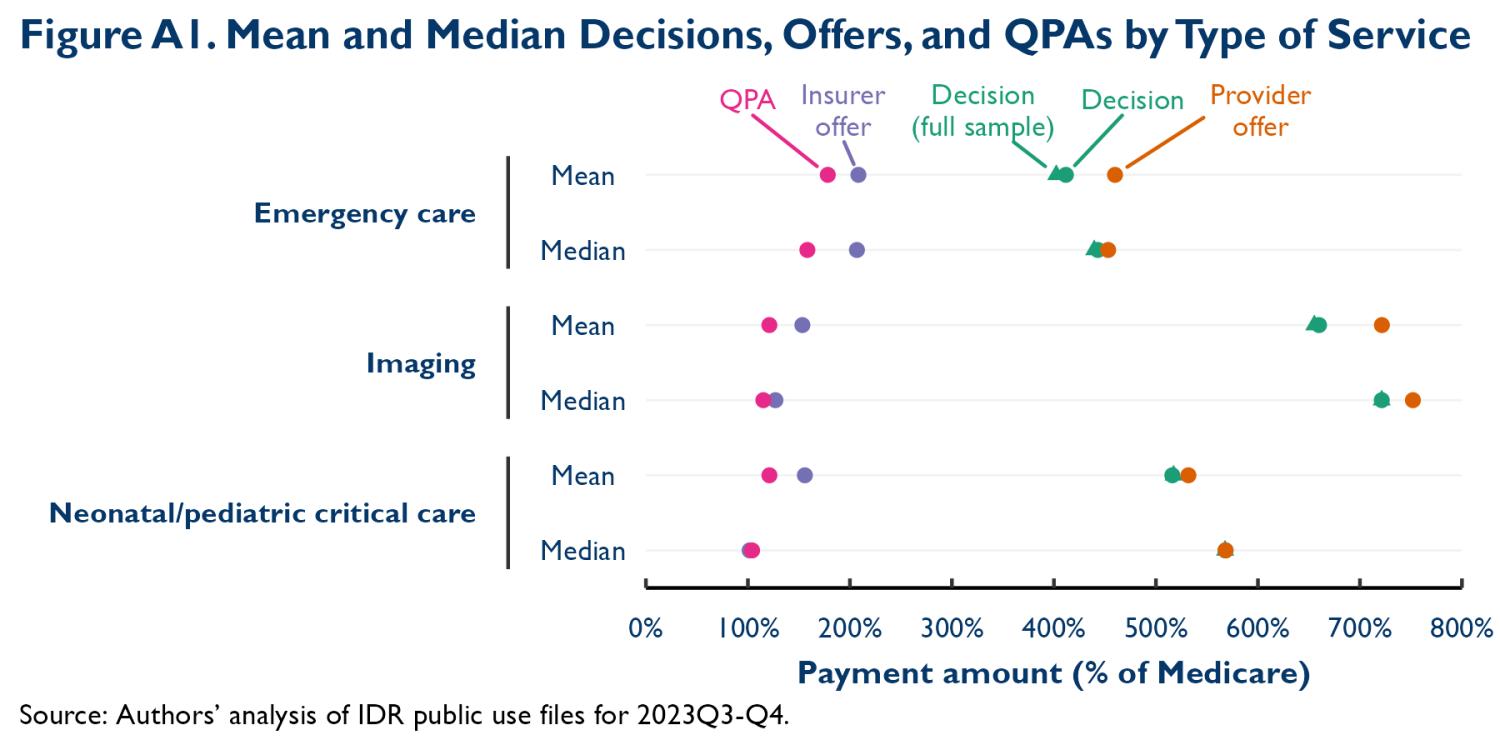

- In our original analysis, we focused on the median prices emerging from IDR and reported means in an appendix because medians were less likely to be distorted by some types of data quality problems. Because we have somewhat higher confidence in the quality of the data reported for the second half of 2023 and because means are the more useful measure for many purposes, we have elected to focus on means in this analysis, although we continue to report medians in Appendix Figure A1. In any case, our main qualitative conclusions would be the same for either measure, as was also the case in our prior analysis.

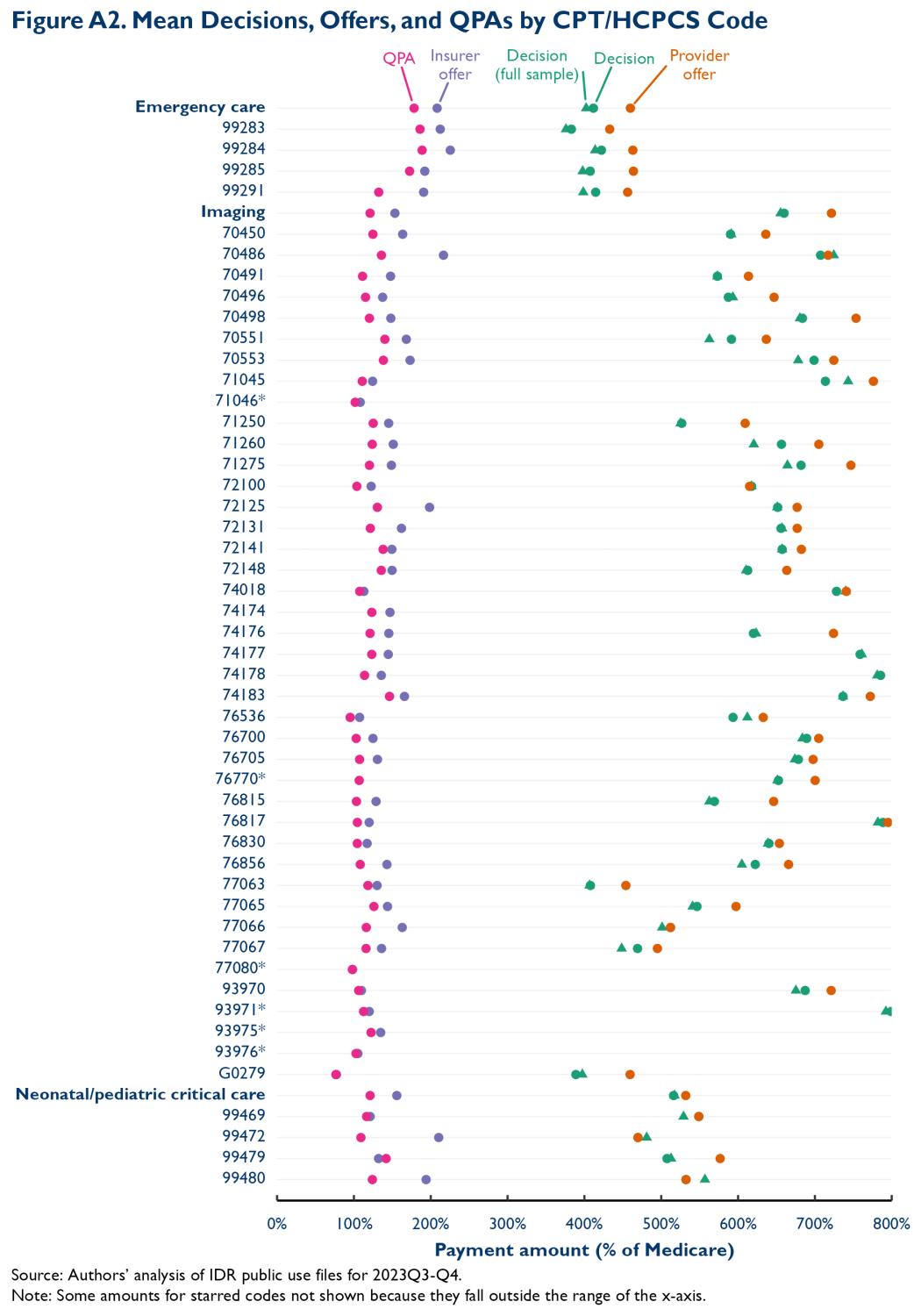

- Because of the methodological changes described in the appendix, the estimates in this analysis are not exactly comparable to our prior estimates. However, the effect of those methodological changes is likely relatively modest and may actually be muting the observed increase from early to late 2023. Additionally, changes in the mix of service codes appearing within each category do not appear to be a major contributor to the difference between the estimates for the two halves of 2023. When we reweighted the data for the second half of 2023 to reflect the mix of services observed in the first half of 2023, our estimates were almost identical. This reflects the fact that the compositional changes that did occur were small and the fact, depicted in Appendix Figure A2, that the estimated Medicare ratios vary only modestly across different services within the same category.

- Whereas the analyses underlying Figure 1 include all line items that report the IDR decisions amount, the analyses reported in Figure 2 reflect the sample of line items that also report valid offers from both parties and the QPA. Appendix Figure A1 shows that mean IDR decisions during the second half of 2023 are nearly identical in the two samples. Our prior analysis found that this was also the case for the first half of 2023.

- An additional potential driver of this gap is the fact that the QPA is adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI), whereas, as described in the appendix, the estimates of mean pre-NSA in-network prices we present here were (implicitly) adjusted based on the actual trend in the prices that commercial insurers pay for physician services. In practice, however, this is likely a minor factor: Producer Price Index data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that the prices private insurers paid for physician services were about 7% higher in 2023 than in 2019, whereas the CPI-derived increase in the QPA was approximately 8% for 2023.

- We take this approach for providers with names that: (1) include the phrase “emergency center”; or (2) include the phrase “memorial village” but do not include the word “physician.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Outcomes under the No Surprises Act arbitration process: A brief update

July 31, 2024