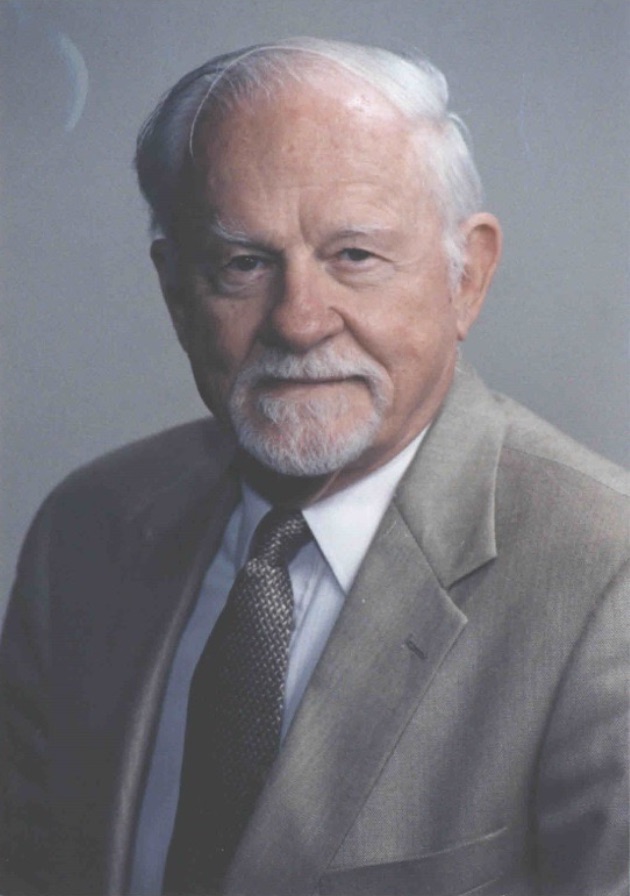

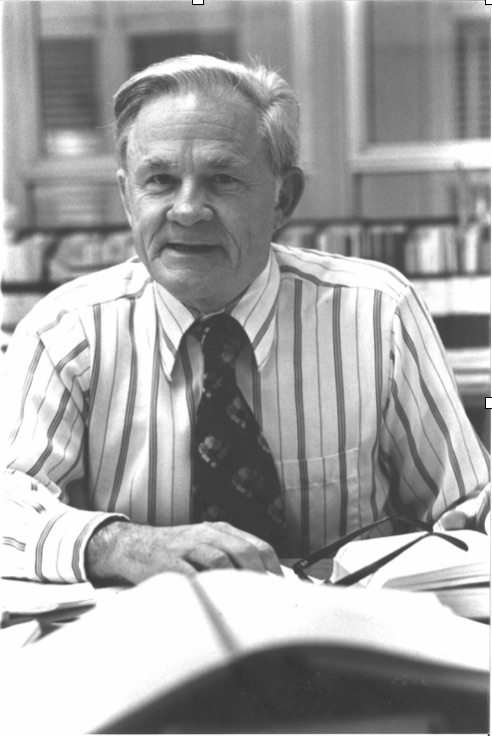

The Brookings community mourns the death of beloved scholar and economist Charles L. Schultze, who passed away on Tuesday, September 27, 2016 at his home in Washington, DC. He was 91.

A public servant

Schultze, known as Charlie to his family and colleagues, started his tenure as a senior fellow at Brookings in 1968, serving as director of the Economic Studies program from 1987 to 1990. He has been a senior fellow emeritus since 1996. Before and during his career at Brookings, Charlie served in three presidential administrations: as assistant director of the Bureau of the Budget under President Kennedy; director of the bureau from 1965-68 under President Johnson; and chairman of President Carter’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA). In 1984, Charlie served as president of the American Economic Association.

In a 2010 oral history interview with The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, he called being the budget director “the greatest job in government.” A 1967 Georgetown University Alumni Association magazine profile noted that, at the time, he was the youngest person to ever hold that post. “He is a demanding boss,” the magazine reported, “but his demands upon himself are the stiffest. He works an eleven- or twelve-hour day, and then takes work home three or four nights a week. He is a no-nonsense executive, impatient with the ‘symbols’ of power, such as a fancy office or two-hour-with-cocktails lunches, and he is likely to smoke, or chew gum at work.”

While nearly everything of importance in government crossed the budget director’s desk, Schultze noted that the CEA job was much tougher, because the position meant he had to fight for standing in the White House.

Colleagues remember

His colleagues at Brookings remember his leadership, humor, and contributions to economic policy understanding and practice.

Charlie Schultze became for me the model of what an economist should be and do. As part of my job on the staff of the Council of Economic Advisors half a century ago, I sat in on budget review sessions chaired by Lyndon Johnson’s budget director, Charles Schultze. Quick, witty, deeply informed, using economics to sharpen decisions regarding billions of public spending, parrying with the extraordinary staff who worked for him, he dazzled a wet-behind-the-ears newby from graduate school. My admiration for his insight, good sense, balance, and tenacity, strong then, never faltered. That image of Charlie was who I aspired to be when I grew up and, in many ways, still do.

— Henry Aaron, senior fellow, Economic Studies

I came to Brookings a bit starry-eyed seeing some legendary economists roaming the halls. But it wasn’t long before Charlie went from legendary economist to colleague and friend, thanks to his kindness, wit, insightfulness, and willingness to share policy war stories (and they were great stories indeed!). On a number of occasions, while reading about a new proposal, I’d roam over to Charlie’s office to hear him explain how the idea was actually a rehash of something he grappled with previously in government. He’d then take apart the idea using clear economic reasoning, combined with deeply informed knowledge of the workings of government, all presented with wit and good humor. I will miss him.

— Ted Gayer, vice president & director, Economic Studies

[as related by Charlie Schultze to Michael O’Hanlon]

When he was LBJ’s budget director, he was down at the Texas ranch one Christmas break to prepare the budget, and a few congressmen were visiting too. Walking with the president, they happened upon some wet concrete. Johnson insisted that everyone write their name in the concrete before it dried. After the congressmen had finished, LBJ said, “come on Charlie, you too.” Unfortunately, Charlie miscalculated, and ran out of room before he could put the letter “e” onto his last name, so the name read like the Snoopy author rather than Charlie’s correct spelling. Johnson saw it, and called out to the congressmen, saying, “guys, you wonder why we have so many problems in Washington? I have a budget director so damn stupid he doesn’t even know how to spell his own name.”

– Michael O’Hanlon, senior fellow, Foreign Policy

Charlie was the quintessential Brookings economist: well-grounded in theory, fully informed about the facts, a creative and careful thinker who had a gift for cutting to the essence of a problem, explaining it in a crystal clear way, and drawing out the implications for what we should do. He was the proverbial gentleman and scholar. I will cherish memory of our interactions and the many things I learned from him.

— Bill Gale, senior fellow, Economic Studies

Charlie Schultze was a splendid economist, public servant, and Brookings fellow. When such a splendid colleague leaves us, my thoughts turn to a John Donne passage:“All mankind is of one author, and is one volume. When one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language. And every chapter must be so translated. God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God’s hand is in every translation. And his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again, for that Library where every book shall lie open to one another…”

The images of related chapters and of fine books lying open to each other in a great Library are comforting when acknowledging our loss of Charlie. Charlie’s chapter in the great Library of life has been outstanding. His publications and reports alone merit a prominent place. His devoted commitment to public service is legendary. Maybe the greatest emphasis of all should be on his humane, generous, and caring traits as an individual. He was an exemplary colleague and friend whose inner light illuminated all those around him.

— Ralph Bryant, senior fellow, Economic Studies

I have lost a wonderful colleague and friend; Brookings has lost a valued, long-time leader; the economics profession has lost one of the most brilliant and able in its ranks. But Charlie Schultze will always be remembered with the greatest fondness as that rare combination–a great and a good man.

— Ambassador Stuart E. Eizenstat, excerpted from his tribute on the Brookings website.

An influential body of research

Schultze was instrumental in launching the original Brookings series “Setting National Priorities” in the early 1970s. These highly influential volumes became standard college texts for years and also influenced the creation of the Congressional Budget Office. One of his chief collaborators on this project, Alice Rivlin, now a Brookings senior fellow, became the first director of the Congressional Budget Office in 1975.

Some highlights of his important body of work while a Brookings scholar include the 1992 volume “Setting Domestic Priorities: What Can Government Do?” (Brookings, 1992). In it, Schultze and co-editor Henry Aaron offered the independent analysis that is a hallmark of Brookings scholarship. They wrote that: “This book is a pragmatic blend of conservative and liberal approaches” to some of the problems of the day, including wage stagnation, child poverty, and cynicism about government and elected officials. The book, they continued, “is not built on the belief that government can fix every problem” but “it is grounded in the idea that government can take specific actions to make some things better.”

In 1993, Schultze authored a series of imaginative “memos to the president” on economic principles and policy issues. Published as “Memos to the President: A Guide through Macroeconomics for the Busy Policymaker” (Brookings, 1993), the short memos remain instructive today. Answering a question, “Why the ‘Macro’ in Macroeconomics?” for example, Schultze advised the president that “Many commonsense notions that are perfectly plausible when applied to the behavior of firms and individuals can be quite wrong when transferred to the world of macroeconomics.”

Schultze was able to translate his deep technical knowledge of economics into accessible language for a wider audience of readers, as evidenced by one particular article for the “Brookings Review” magazine. In the Summer 1989 edition, his wittily titled “Of Wolves, Termites, and Pussycats; Or, Why We Should Worry About the Budget Deficit” deployed the curious “economic bestiary” to explain three competing views of the budget deficit. He counted himself, and the majority of economists, as “the termites in the basement.”

His other works include, “An American Trade Strategy: Options for the 1990’s,” co-edited with Brookings Senior Fellow Robert Z. Lawrence (Brookings, 1990); “American Living Standards: Threats and Challenges,” co-edited with Lawrence and Robert E. Litan (Brookings, 1988); “Barriers to European Growth: A Transatlantic View,” with Lawrence (Brookings, 1987); “Economic Choices 1987” (Brookings, 1986); and “Other Times, Other Places: Macroeconomic Lessons from U.S. and European History” (Brookings, 1986).

Schultze also contributed a number of articles to the “Brookings Papers on Economic Activity,” a leading journal of economics published by Brookings since 1970.

His last Brookings paper, “Clean Energy: Revisiting the Challenges of Industrial Policy” (2012) was co-authored with Senior Fellows Adele Morris and Pietro Nivola. In it, Schultze and his co-authors discussed the economic efficiency of the Obama administration’s green energy program.

In the midst of this serious policy analysis, Charlie made time for lighter moments, including an appearance on comedian/impersonator Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Da Ali G Show” on HBO in 2007. Watch Charlie fist-bump “Ali G” and offer the advice, “Don’t be high when you are buying and selling stock.”

—

A native of Alexandria, Virginia, Charlie graduated from Gonzaga High School (1942) and received both his bachelor’s (1948) and master’s (1950) degrees in economics from Georgetown University. He was awarded a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Maryland in 1960.

In 1943, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served for three years in the infantry. He was awarded both a Purple Heart and Bronze Star during service in the European theater of World War II. Charlie was married to Rita Hertzog for 67 years before her death in 2014. He is survived by his six children, 16 grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

Read his “Washington Post” obituary here. A memorial service will be held at Brookings at 2:00 p.m. on November 4. In lieu of flowers, donations are requested for Best Buddies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

On the passing of Charlie Schultze: Brookings economist, public servant, WWII veteran

September 27, 2016