President Barack Obama is welcoming Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan to the White House this Wednesday and Gabonese President Ali Bongo on Thursday. Later this month, First Lady Michelle Obama embarks on her second official solo trip, this time to South Africa. While oil geopolitics play a role in the U.S. president’s agenda, the heightened emphasis on sub-Saharan Africa, and especially on its economic progress, is in stark contrast to how the region was cast in the past. For decades sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) was inappropriately cast by many in the West as a wholesale “basket case”; an abjectly poor, economically stagnant and corrupt region entrenched in perennial violent conflict. We had rejected such an “afro-pessimist” view in the past, and now the pendulum has swung to the other extreme. The region’s overall performance in recent years – featuring economic growth and reductions in poverty and child mortality rates, among other achievements – has many heralding Africa’s “new dawn”.

Yet, our analysis suggests that while progress in a number of African countries has been laudable, one should be wary of premature exuberance. The African countries on Obama’s diplomatic agenda in coming weeks not only demonstrate the continent’s achievements in areas like democratic consolidation (South Africa), but they also illustrate some of the region’s major challenges such as democratic accountability and high levels of corruption (Gabon). The high variance in governance and development performance across the SSA warrants further analysis beyond regional averages and comparisons with the past. Contrasting the performance of African countries with that of other emerging economies provides added insight into the challenges facing the continent.

Africa is a Diverse Continent

Too often sub-Saharan Africa has been viewed as a singular unit rather than a conglomeration of 48 individual countries. While income per capita in the region grew at an average rate of 2.1 percent annually over the last decade, per capita growth rates ranged from -6.0 percent in Zimbabwe and -4.1 percent in Eritrea to 15.3 percent in oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, 7.7 percent in oil-rich Angola and 6.2 percent in Sierra Leone. A high variation across countries in Africa is also evident on a variety of other economic and governance indicators.

Radelet (2010) explores cross-country differences by distinguishing between groups of countries based on economic performance, classifying SSA into four groups – emerging (17 countries, such as Ghana and Ethiopia), threshold (six countries, such as Liberia and Benin), oil exporting (nine countries, such as Angola and Congo) and other, which we re-label as fragile (16 countries, such as Somalia and Zimbabwe). [1] According to Radelet, countries in the emerging category have experienced economic growth and poverty reduction since the mid-1990s, while threshold countries have seen similar, though less dramatic, economic changes. Oil exporters have experienced uneven and volatile progress, and fragile countries have seen few economic improvements.

On average, incomes per capita among Radelet’s group of 17 emerging SSA economies grew at 3.2 percent annually over the last decade. Growth in emerging economies outpaced threshold (1.7 percent growth) and fragile (-0.5 percent growth) countries, though not oil producing ones (4.5 percent). However, it is important to note that even among this elite group of emerging countries there is a high variance in both economic and governance performance. [2]

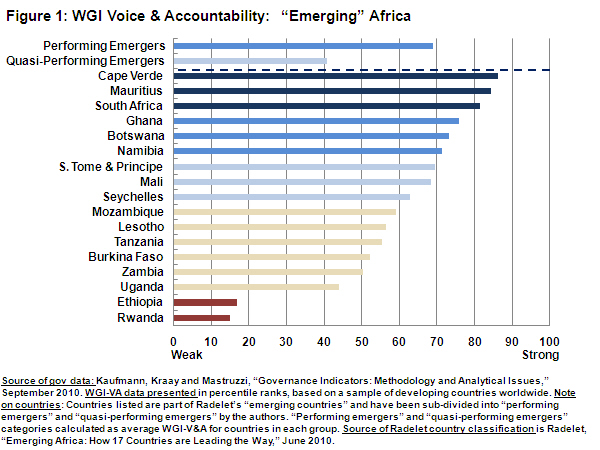

Since research has shown that the quality of governance impacts long-term growth and development, it is particularly important to emphasize governance alongside short-term economic performance. We have reviewed the performance of SSA countries on a broad range of governance indicators, including voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption from the Worldwide Governance Indicators, and political rights, civil liberties and press freedom from Freedom House. We find that the 17 emerging economies category can be split into at least two groups – those that we label as performing emergers, which have had adequate growth rates and relatively satisfactory levels of governance, and the quasi-performing emergers (Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia), which have exhibited adequate per capita income growth in recent years but where governance performance remains subpar.

The quality of governance across countries in the region differs considerably, and even among the “emerging” group of countries in SSA we observe substantial variation in voice and democratic accountability (Figure 1). On average the group we label performing emergers rates in the top half of all developing countries; by contrast, the group of quasi-performing emergers rates in the bottom half of all developing countries on this important governance dimension. To illustrate, among the 17 emerging SSA economies some stellar countries like Mauritius and South Africa (performing emergers) exhibit voice and democratic accountability on par with Slovakia and Brazil, while countries like Rwanda and Ethiopia (quasi-performing emergers) are on par with Afghanistan and Azerbaijan. Further, according to Freedom House, while the 13 performing countries among the emergers have either a free (39 percent) or at least a partly free press (61 percent), with the exception of Uganda (partly free), the press in “quasi-performing” countries is rated as un-free.

While it may be tempting to generalize and hail sub-Saharan Africa’s “new dawn”, it may be more accurate to hail it as: a dawn of a select few performing emergers with strong growth and good governance. This group represents only a quarter of the region’s countries and a fifth of its population.

Cross-Regional Benchmarking Provides Insights

We have noted that several SSA countries have seen improvements in social and economic indicators over the past decade. But benchmarking against other developing countries and regions provides additional perspective.

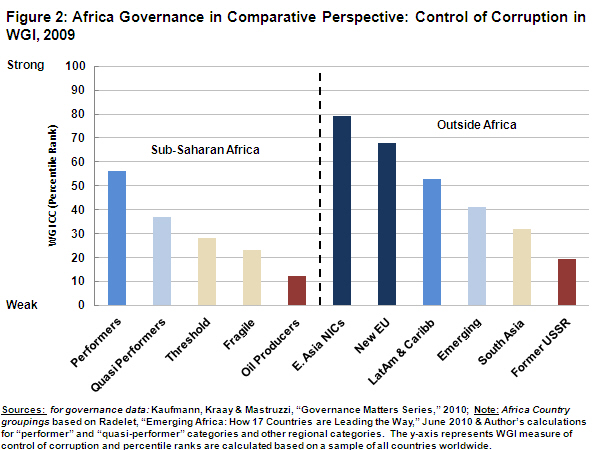

Some sub-Saharan African countries exhibit strong economic performance relative to countries in other regions, though several do not. Over the last five years, average per capita incomes in SSA grew slower than in any other developing region (2.3 percent growth). On the one hand, the growth performance of SSA’s performing emergers (3 percent growth) was on par with the regional average for all countries in Latin America (2.9 percent growth) and with the new European Union countries (3.2 percent growth). On the other hand, countries in SSA’s “threshold” (2.2 percent growth) and “fragile” (0.2 percent growth) groups performed well below these groups and on par with countries that were either generally misgoverned or harder hit by the recent global financial crisis.

A similar pattern emerges when comparing governance across world regions. As Figure 2 suggests, the extent of control of corruption among performing SSA economies is similar to that of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), but below the levels of East Asian newly industrialized countries and newly acceded EU countries. Quasi-performing emerging economies of SSA display governance levels similar to those of developing East Asian countries, and threshold and fragile countries have governance levels on par with South Asia and Former Soviet Union economies. Notably, SSA oil producers have the weakest control of corruption among any of these groups (Figure 2).

Our assessment of economic and governance progress in SSA countries points to both encouraging and sobering news. About a quarter of the region’s economies are performing well relative to their neighbors as well as their competitors worldwide in areas such as growth and governance. Yet the majority of sub-Saharan African countries are still lagging behind, in growth, voice and democratic accountability, control of corruption and other important dimensions of governance (including political stability, rule of law and government effectiveness).

A key question is how to foster continued progress in performing countries and promote growth-and development-enhancing change in non-performing ones. Rather than providing a long list of recommendations—which would be futile given diversity of the countries— we put forth some principles to spur a discussion on priorities for reform.

Focus on Targeted Proposals

The challenges facing many African countries are complex, ranging from low productivity to high unemployment and from an underdeveloped middle class to poor health outcomes. It is often tempting to draw up a long list of reforms trying to tackle each one. But, not every sectoral constraint is best addressed through an isolated intervention, and resources, political capital, and institutional capacity are limited. Each country also has its own first-order priorities. Therefore, a country should focus on key reforms that are mostly likely to have the largest impact at every stage. While recognizing the importance of other areas, we focus on governance, which affects all economic sectors and is central to achieving sustainable development.

Fundamental and proximate causes of underdevelopment differ. The numerous causes of underdevelopment in SSA can be divided into two categories: proximate and fundamental. For instance, many countries in the region lack a strong middleclass, which may hinder domestic savings and investment. While it is impossible to “inject” a middle class into Africa, it is possible to foster its development by tackling the underlying constraints that hinder its growth.

A fundamental cause of underdevelopment is poor governance. Research shows that good governance fosters sustained growth in the longer term through domestic and foreign investment, private sector development, improved public sector management and sectoral development. Additionally, voice and accountability, political stability, corruption control and rule of law are crucial for equitable growth and middle class development. The latter are often identified as key constraints to progress in sub-Saharan Africa, but they represent proximate causes.

Governance has a large development dividend. Through various channels improvements in governance may spur progress in areas that are currently hindering development in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions.

• Improved governance facilitates incomes growth. Previous research suggests that there is a large development dividend to improved governance. In the long run, on average incomes could rise three-fold if the very weak control of corruption in Zimbabwe was improved to those of Senegal, or then from those of Senegal to the middling levels of countries like Botswana. Figure 3 clearly shows the strong positive relationship between control of corruption and income per capita over time. Improvements in other aspects of governance, including political stability and rule of law have similar effects on incomes, and causality has been found to run from improved governance to higher incomes (rather than the other way around).

• Voice and democratic accountability promote equitable and sustained growth. Recent events in and around the region have highlighted the importance of voice and accountability. Countries in North Africa that experienced high growth in recent years, such as Tunisia and Egypt, have recently experienced social unrest and undergone regime change. Instability in the region has stemmed from popular dissatisfaction with the governance deficit, highly inequitable growth, unproductive or non-existent job prospects and corrupt institutions. While the realities and challenges of SSA differ some from those of North Africa, many countries in SSA still face a large democratic governance deficit and corrupt institutions, even within the emerging group (Figure 1). The risk of unrest is real in a number of SSA countries.

Such social unrest and prolonged civil wars also undermine economic and social development. Research has shown that conflicts reduce growth rates, even during post-war recovery, and have a severe negative impact on human health. In fact, nearly half of Radelet’s fragile economies can be considered conflict or post-conflict countries.

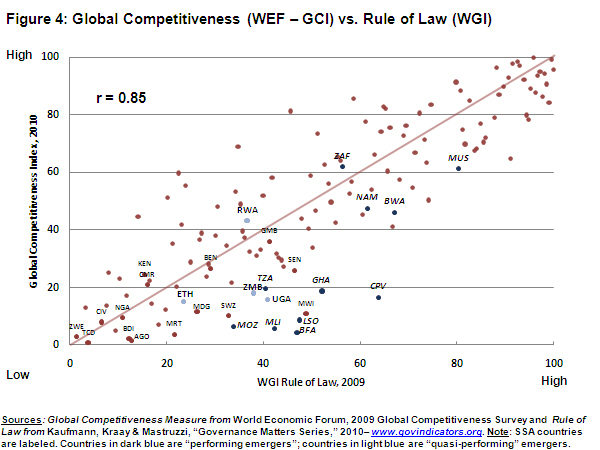

• Good governance promotes competitiveness and investments. Numerous studies have found a positive relationship between private investment and high regulatory quality and control of corruption. Weak regulations and high corruption create uncertainties in the economy and may discourage investment and result in ineffective allocation of resources and a diversion of funds. Other components of good governance are also strongly connected to private sector growth. As Figure 4 indicates, countries with stronger rule of law are more competitive.

Furthermore, if we look at specific constraints to private sector development, such as infrastructure, the issue of governance again arises. A recent World Bank report on transportation prices and costs in Africa found that high transportation costs in Africa were driven more by poor regulations than by poor infrastructure. Regulations currently impose substantial barriers to entry, thus allowing existing transport companies to maintain a monopoly and charge prohibitively high prices.

• Good governance also has a positive impact on human development. As a result of increased government transparency and public accountability, the portion of allocated public expenditure that reached schools in Uganda rose from 13 percent in 1991 to nearly 80 percent in 2001. Good governance, and particularly female empowerment, helps reduce child and maternal mortality rates, which continue to be unacceptably high in many countries. Gender equality and female empowerment are likely to feature prominently in Michelle Obama’s agenda as she travels to South Africa later this month.

Donors can signal their commitment to governance. Continued donor engagement in sub-Saharan Africa is critical. At the same time, improving the allocation and effectiveness of this aid is in the interest of both donor and recipient countries. Currently, the lion’s share of aid is allocated to poorly governed countries, many of which have not been making concerted strides toward good governance. Figure 3 suggests the extent to which quasi-performing emerging countries (such as Ethiopia and Uganda) as well as fragile countries (such as the DRC) and some oil producers (Sudan and Nigeria) receive more aid than performing countries, such as South Africa. Enhancing aid selectivity, finding better instruments to channel aid, and linking it to concrete governance improvements can help ensure that donor aid to recipient countries is used effectively, while sending a message to all countries that good governance will be rewarded.

There is reason to be optimistic about Africa’s future and the region’s successes are expected to be highlighted by President Obama and the first lady during their upcoming meetings with the leaders of Nigeria, Gabon and South Africa. Many African countries are now recording positive (and sometimes substantial) growth, reducing poverty rates and attracting more foreign investment. However, it may be premature to declare success across the African region. As Figure 3 indicates, about a quarter of SSA countries, including South Africa, are performing well. These emerging economies demonstrate that economic, social and institutional change is possible. Yet, most of the remaining SSA countries still face substantial governance and economic constraints to growth. It is important to recognize that performance is very varied across the African region and that many countries, like Gabon, still face daunting governance challenges.

Editor’s Note: In March, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies convened a conference on the factors that have contributed to Africa’s accelerated growth over the past decade. Daniel Kaufmann contributed to the panel on governance. This article builds on that presentation.

Footnote:

[1] In his contribution, Radelet classifies these countries as “other.” For the purposes of this piece we have renamed this group as “fragile,” having taken into consideration both growth and governance in these countries.

[2] The group of 17 emerging countries consists of: Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ghana, Lesotho, Mali, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Seychelles and South Africa remain in the emerging category (although their income per capita growth rates drop below 2% if considering the period 1996-2009 or 2010 rather than the original 1996-2008 period).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edOn Africa’s New Dawn: From Premature Exuberance to Tempered Optimism

June 7, 2011