Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

It’s fair to say that newly-elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi took most Indian and international observers by surprise by embarking on a highly visible global tour to build relationships during his first year in office. Racking up both air miles and international newspaper column inches (to say nothing of Twitter mentions), Modi travelled far and wide, concentrating on two sets of countries: India’s neighbours and the major powers, especially in Asia—a category which, in Modi’s view, includes the United States. The highest profile visits were to Tokyo, Washington and Beijing, while both Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping came to New Delhi.

Seen through one lens, the series of visits updated an old Indian strategy – that of remaining “non-aligned” with the competing great powers on the world stage. It was updated, in that during the Cold War ‘non-alignment’ was about keeping India’s distance from the two superpowers. The India-Russia relationship has clearly survived transitions in contemporary geopolitics; the India-China relationship continues on its dual track of strategic competition and economic cooperation; and the India-US relationship has now been building over the course of almost two decades. The difference now is that India sees itself—and is seen by others—as one of the great powers, or at least a rising and potential member of that category.

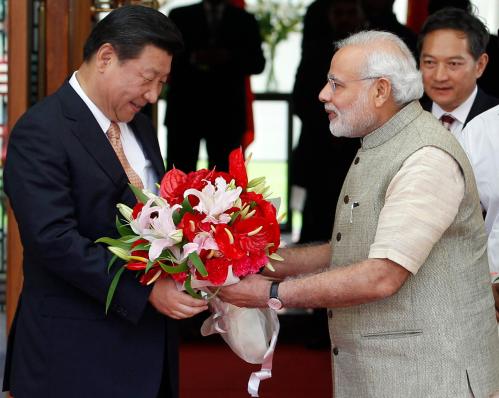

The India-China relationship is perhaps the most complex here. Before Modi travelled to Beijing, President Xi visited India in September 2014. The trip was supposed to cement closer economic ties, but ended up being overshadowed by military manoeuvres along the contested India-China border in the Himalayas. Xi’s decision to mount those manoeuvres at the time of the visit (no other explanation is credible), perhaps to pressure Modi, backfired and the visit produced a shift in the balance of diplomatic power—in India’s favour. Modi’s May 2015 trip to Beijing was more successful, but on India’s terms.

Download the Complete Briefing Book

Among the apparent ‘non-aligned’ pattern of Modi’s travels, two trips stood out, and suggest a different sub-theme. These were his trip to Washington, and President Barack Obama’s unprecedented return visit to New Delhi, in less than six months, for the Republic Day. These trips renewed cooperation on issues like defence ties and reignited business interest. More importantly, they were a clear signal of a decisive upshift in the relationship away from the on-again, off-again flirtation of the last two decades to a more sustained strategic engagement.

Thus while ‘non-aligned’ was one frame for Modi’s travels, another dimension was being developed in the India-U.S. track, one that Modi himself described by invoking the term “natural allies”.

Indian diplomats and officials have long rebuffed a quasi alliance, concerned that the U.S. would be an unreliable friend and that too close an association with Washington would alienate Beijing without bringing genuine strategic advantages. As India’s neighbour China looms large in Indian calculations, especially now that Chinese growth has so spectacularly outstripped India’s (to the point where the Chinese economy is five times larger than the Indian economy.)

Modi clearly sees that the India-China relationship is not likely to move off its long-established pattern of what former Indian National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon calls “duality” — deepening economic cooperation not necessarily leading to lessening strategic tension. So while closer ties with the United States might irritate China, it would not change the fundamentals and might bring benefits in the wider Asian balance. What’s more, Modi has been able to deepen the relationship with Washington without sundering India’s long-standing ties with Moscow.

So far so good. There’s nothing officially contradictory about having a “natural alliance” with Washington and maintaining a ‘non-aligned’ stance more generally with the full suite of major powers; natural allies are not treaty allies. As long as great power relations remain moderately stable, India won’t be squeezed between these two views.

But what will happen if wider relationships deteriorate—as they seem set to do. What happens if U.S.-China tensions over maritime boundaries and naval tactics escalate? India is far from neutral on the issues over which China and America will tangle. What happens if Russia and the United States/Europe escalate tensions on Russia’s western border? India doesn’t have to get drawn into that set of issues operationally, but Washington can at times be pretty intolerant of its friends remaining neutral when core issues are at stake. And what will Washington do if its ‘natural ally’ comes under greater pressure, for example along the India-China border? Will Washington actually prioritize the impact on India over its Afghanistan and Pakistan policy?

For now, there’s no tension for India between great power speed-dating and a deeper relationship with the United States. But as events unfold, the tensions are sure to grow. And if the United States wants the India relationship to deepen, it’s going to have to be prepared to make some hard choices.

Modi has had a terrific first year in foreign policy. But in his great power relationship strategy, as with many of his other initiatives, much remains to be seen about how the strategy will play out and where we will be one year from now. Watch this space.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edNon-aligned, or natural allies?: Modi and the challenge of great power relations

IndiaGov@365

June 1, 2015