Last week, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee released their proposed update to the country’s passenger rail legislation. The Passenger Rail Reform and Investment Act (PRRIA) of 2014 not only reauthorizes the federal program for four years, but it also contains a broad suite of sensible reforms to meet Subcommittee Chairman Jeff Denham’s goal of Amtrak running “more like a business.”

Yet, it also continues to avoid the system’s glaring Catch-22. Congress perennially blasts Amtrak for its annual losses on long-distance routes—namely, those stretching over 750 miles—but federal law requires Amtrak to run these same routes.

To address these efficiency and equity issues, federal and state policymakers must have an open and honest debate about whether these benefits are worth such significant financial losses. Otherwise, the country will kick the can down the road yet again on a key infrastructure issue, failing to provide needed guidance, certainty and funding.

To be sure, much is going right for American passenger rail. Overall Amtrak ridership grew an astounding 55 percent between 1997 and 2012, easily surpassing the growth rate in domestic aviation and even inflation-adjusted GDP. And with 88 percent of passengers boarding in the country’s largest metropolitan areas, it’s not a surprise that short-haul corridors—including the Northeast Corridor—are attracting more passengers every year.

While market forces have supported additional growth in short-haul service, federal and state partners have ensured trains are there to meet this newfound demand. Following the previous passenger rail legislation passed in 2008, states have stepped up to cover operational losses on all short-distance corridors outside the Northeast Corridor. This shared responsibility has provided greater financial security for passenger operations, while also incentivizing improved operational efficiencies.

PRRIA doubles down on federal and local reforms like this. It creates fascinating station and corridor development programs, which would increase private sector collaboration and the ability to generate new revenue. It also attempts to make better use of underutilized federal loan programs, offering another method to increase investment and forge new federal-state partnerships.

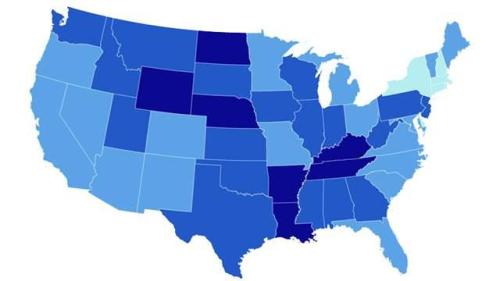

Unfortunately, the bill fails to take a position on the issue of long-distance costs. As our work found in 2013, these routes contribute a disproportionate share of Amtrak’s operational losses and low ridership. And while PRRIA recognizes this area of concern by requiring an independent evaluation, the public already knows the overarching result: It’s the 21st century, and most people simply do not want to travel long distances by train.

That leaves Congress, and states, with a difficult debate, but one that has two clear choices. On the one hand, the country can maintain a truly national rail network that offers geographically-broad coverage, but will invariably come at an operational loss. On the other hand, policymakers may opt for a more limited network focused on large metro-to-metro connections, with smaller losses, but geographic inequity. Given the ongoing fiscal constraints in Washington and beyond, we can’t have it both ways, and our leaders must work together to explore what’s best for the country.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

New Amtrak Bill Still Means the Same Old Funding Debate

September 16, 2014