Just like a good book can make you laugh or cry, a powerful policy narrative can stir the emotions of the public, sometimes sparking controversy along the way. In the summer of 2021, education leaders found themselves on the receiving end of this phenomenon. Across the country, angry parents and community members turned normally mundane school board meetings into chaos after hearing stories of a supposed new threat in schools: critical race theory (CRT).

To education leaders, this was shocking. CRT is a legal and academic theory that scholars have used for nearly 40 years to examine how institutions and legal systems continue to perpetuate racial inequality today. However, conservative activists and politicians had a different story to tell about CRT. Christopher Rufo, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, is viewed as introducing the CRT narrative to the public. Rufo warned that CRT would teach children to “hate each other and hate their country” and that they are “defined by their race, not as individuals.” This produced heated debates about whether CRT should be taught in school—even as the CRT that conservatives described bore little resemblance to the theory used in academic research.

But was that outrage confined to a small-but-vocal group of people, or was the impact more far reaching than that? Could a story—a partisan reframing of a decades-old academic theory—have the power to shape policy opinions, and ultimately, policies?

Anti-CRT narratives and public support for a CRT ban

To examine some of these questions, we identified 11 policy narratives that Republican legislatures and governors used to justify CRT bans during the first wave of bans in 2021. Examples of these narratives are that “CRT indoctrinates children,” “CRT teaches children to be racist,” and “CRT teaches children to feel bad.” We then surveyed 1,500 Michigan adults through the Institute for Public Policy and Social Science Research (IPPSR) State of the State Survey, asking how often they heard these narratives. The survey was completed during September and October 2021, just as the Michigan legislature was debating two bills that would have banned CRT in the classroom.

In our study, we found that these narratives were widespread. On average, respondents reported hearing half of these narratives (with 22% hearing all 11 of them). And hearing these narratives was positively related to support for a CRT ban; the more narratives people heard, the more they expressed support for the legislative ban. Specifically, for every additional narrative that an individual reported hearing, they were six percentage points more likely to support a ban on CRT in schools.

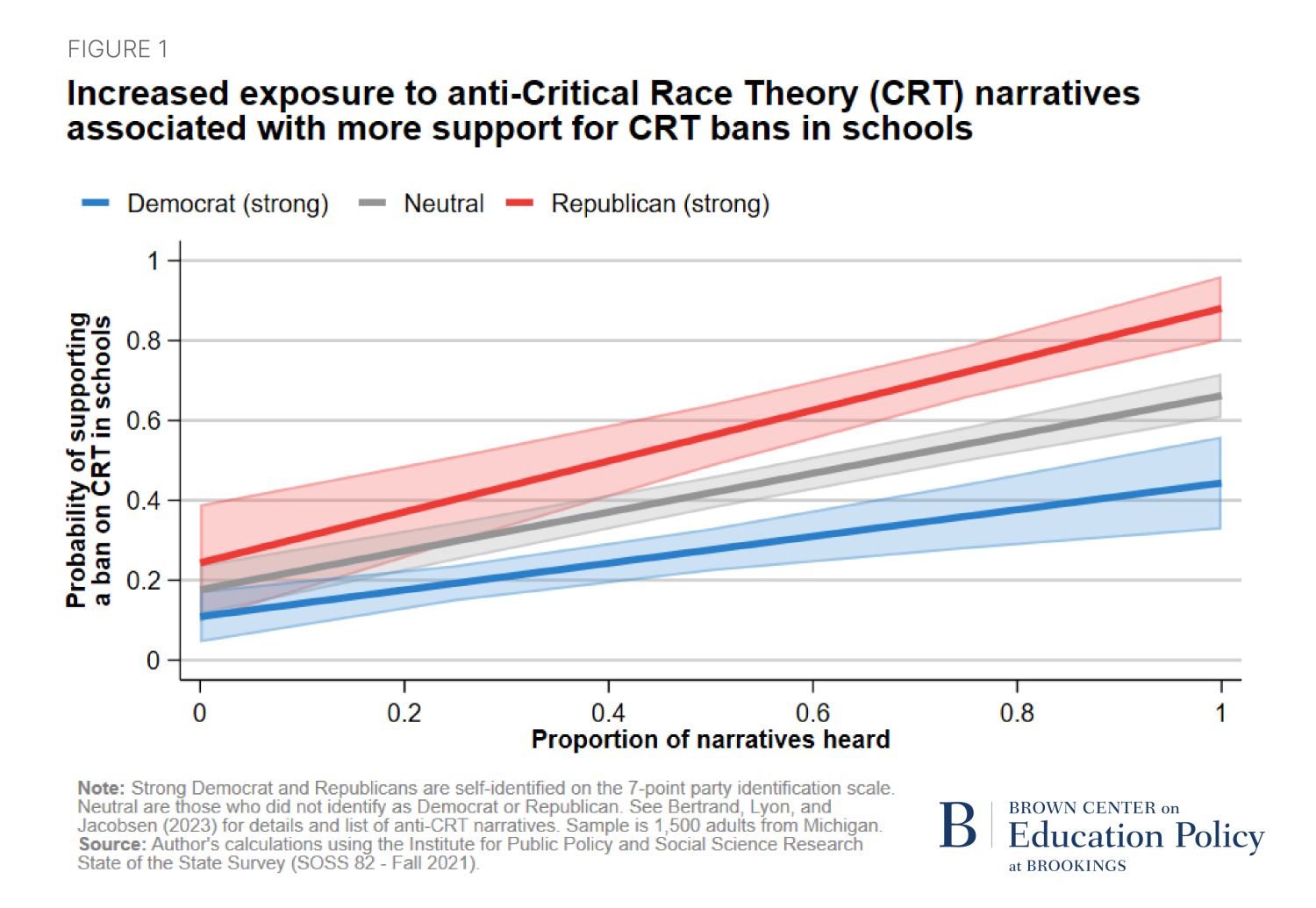

Whether exposure to the narratives caused these differences in attitudes is hard to say. Perhaps people who were predisposed to support an anti-CRT ban (given their strong partisan affiliations) were also more likely be exposed to more anti-CRT narratives (given differences in media consumption habits). Notably, though, we find that all respondent groups’ likelihood of supporting a CRT ban increased with exposure to more anti-CRT narratives.

Figure 1 shows how, across political groups, more exposure to anti-CRT narratives (x-axis) is associated with more support for CRT bans (y-axis). It also shows some differences across parties. If respondents reported hearing none of the CRT narratives, the probability of supporting a CRT ban was not terribly different between strong Democrats (10%) and strong Republicans (24%). However, as respondents reported hearing more narratives, large partisan divides appeared. A strong Democrat who reported hearing all the narratives had a 44% probability of supporting a CRT ban. A strong Republican who heard all the narratives had an 88% probability of supporting a CRT ban.

Anti-CRT narratives and trust in schools

While we might expect a policy narrative to shape opinions of closely related policies, especially on an issue as unfamiliar to the public as CRT, exposure to emotionally charged policy narratives might also shape how we view our schools and teachers more generally. The public has traditionally held high levels of trust in their local schools even while rating the nation’s schools unfavorably. We examined the relationship between exposure to anti-CRT narratives and the public’s perceptions of schools, schooling, and teachers.

For every additional ban-CRT narrative that people reported hearing, they were about two to three percentage points less likely to report trusting their local teachers and schools to discuss race and racism with their students. The relationships weren’t just limited to teaching about race and racism. For example, every additional narrative heard was associated with a four-percentage-point decrease in trust in teachers to supplement their curriculum with additional materials.

As mentioned above, the causal relationships between these factors are unclear. However, our findings are consistent with the possibility that emotionally charged policy narratives could undermine long-held beliefs about schools.

What does this mean for public education?

Although debates about CRT in the classroom may not be as prevalent today as they were in 2021, many school districts are still navigating the fallout from those debates. The proliferation of these narratives has led to at least 18 states and at least 150 school districts adopting CRT bans—bans that limit what schools can teach about race and racism and what resources kids can access about those topics in schools. These new laws have facilitated a wave of efforts to ban books that focus on race and racism while also placing additional stress on teachers at a time when teacher job satisfaction has dipped to historically low levels.

Notably, too, the anti-CRT narratives were quickly followed by narratives attacking how gender and sexuality is discussed in schools. In addition to CRT bans, new regulations at the district and state level are restricting how teachers can discuss gender and sexuality. Together, they have the potential to further undermine trust between the public and local schools. Declining trust poses a serious threat to the education system if, for example, it materializes in less support for public education funding.

However, as much as narratives can undermine long-held beliefs about schools, counternarratives may be able to rebuild and strengthen trust in public schools. Already, we have seen countermobilization at the local level, resisting book bans and flipping back board seats previously held by Moms for Liberty-supported candidates. Public education advocates have an opportunity to instill a reinvigorated sense of pride in U.S. public schools. To do so, advocates would do well to remember the impact that powerful narratives can have in shaping public opinion.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).