Below is Chapter 1 of the 2026 Foresight Africa report, which brings together leading scholars and practitioners to illuminate how Africa can navigate the challenges of 2026 and chart a path toward inclusive, resilient, and self-determined growth.

Leveraging Africa’s natural resource wealth to bridge the financing gap

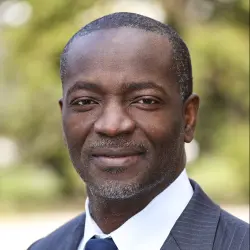

Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly and Wafa AbedinDespite sluggish global economic growth prospects, Africa is demonstrating resilience in the face of a series of major global shocks, from the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to disruptions caused by geopolitical conflict and trade policies. Economic growth in sub- Saharan Africa is projected to remain steady at 4.1% in 2025 with a modest increase in 2026.1 At the same time, the continent’s population continues to expand rapidly and will double by 2050. This demographic momentum and economic resilience present both significant opportunities and formidable challenges, foremost among them the need to scale up investment to create jobs at scale and expand social and economic opportunities. Among the obstacles, none is arguably more important than financing for development. We estimate that sub-Saharan Africa needs at least an additional $245 billion per year in financing. With national savings subdued and external financing dwindling, it is now imperative to explore innovative ways to unlock domestic resources. The natural resource endowment of the region, valued at over $6 trillion in 2020,2 offers the largest untapped potential and the most promising pathway to mobilize domestic financing at scale.

Global aid in decline

The global aid framework is currently at an inflection point, marked by tight borrowing conditions and a deterioration of available external financing. Official development assistance (ODA) fell by 9% in 2024, according to OECD estimates, and it is projected to decline by another 9-17% in 2025,3 reflecting a broader rethinking of global aid priorities among donor countries. The dissolution of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)—previously the world’s largest development agency—illustrates this shift.4

Africa urgently needs substantial financing to accelerate its development agenda—highlighting the imperative of strengthening domestic resource mobilization.

Borrowing on international capital markets offers little relief. The era of ultra-low global interest rates that once encouraged private borrowing has ended, leaving limited fiscal space and far higher borrowing costs. More than 50% of low-income countries in Africa are either in or at high risk of debt distress.5 Annual expenditure on debt service in the region exceeded $101 billion last year,6 crowding out spending on health, education, and social protection. Foreign direct investment flows also remain subdued and increasingly volatile, amid heightened investor risk aversion.

The deterioration in external financing conditions comes precisely at a moment when Africa urgently needs substantial financing to accelerate its development agenda—highlighting the imperative of strengthening domestic resource mobilization.

The imperative of domestic resource mobilization

The challenges facing the continent in financing its development agenda are substantial. Over the next five years, sub-Saharan Africa’s financing gap is projected to average at least $245 billion annually, reflecting the widening gap between investment needs and available resources.

Figure 1 shows that domestic savings rates averaged under 20% of GDP and are expected to remain at around this rate in the coming years.7 Accordingly, investment rates have remained subdued at just over 20% of GDP. This rate is significantly below the minimum 30% investment rate generally required over time to finance development.8

This sizable financing shortfall cannot be addressed with external financing alone, not only because of its volatility, but also because it would leave African economies vulnerable to economic instability from large current account deficits, high indebtedness, and balance of payment crises.

Policy options to boost domestic revenues

There are a few promising approaches to boost domestic resources. The first is optimizing the collection of tax revenues which currently falls short of the tax capacity. Brookings research shows that sub-Saharan African countries have a relatively low taxation capacity at 20% of GDP, which largely reflects a narrow tax base due to the high share of the informal economy. Even so, tax revenues only average about 15% of GDP. Improving governance in revenue collection, including combatting corruption and strengthening transparency, can raise tax revenues by 3.9 percentage points closer to the 20% capacity.9 This would mobilize roughly $94 billion dollars, on average, over the next 5 years.

Recent international efforts to promote fair taxation and curb illicit financial flows also have the potential to boost domestic resources. UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that Africa loses about $90 billion annually from illicit financial flows, reflecting the critical importance of addressing tax avoidance by multinational enterprises and creating a more equitable international tax system.10 Both the OECD Inclusive Framework and the U.N. Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation are important efforts in this regard. While the ongoing efforts at the local and international levels will go a long way to fill the financing gap, the underleveraging of Africa’s natural resource wealth offers, arguably, the largest untapped potential to unlock domestic resources.

Leveraging natural resource wealth

Sub-Saharan Africa’s natural resource wealth was estimated at over $6 trillion in 2020, with renewable resources valued at over $5.17 trillion and nonrenewable natural resources valued over $840 billion.11 These estimates, however, are likely undervalued as the available data do not account for the numerous resource discoveries in recent years. The continent holds at least 30% of the proven critical mineral reserves and, by some estimates, Africa could boost its GDP by at least $24 billion annually with the right investments12 (For more on unlocking Africa’s mineral wealth, see Chapter 3.)

While Africa holds vast reserves of critical minerals essential for the energy transition, much of this wealth is exported as raw materials with little value addition. By scaling local processing and moving up the value chain, Africa can capture greater value from its resources, finance its development agenda, and create jobs. The IMF estimates that global revenues from the extraction of copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium will total $16 trillion (2023 dollars) over the next 25 years, and sub-Saharan Africa is poised to reap over 10% of these revenues, or nearly $2 trillion (2023 dollars).13

Africa’s fossil fuel abundance represents another major opportunity for economic growth. The continent holds 7.2% and 7.5% of the world’s proven oil and gas reserves, respectively.14 The ability to harness this wealth should not be constrained by the global agenda on decarbonization. While limiting carbon emissions is a collective responsibility, Africa’s share of emissions remains relatively low at about 3-4% of global CO2 emissions,15 despite constituting 20% of the world’s population. Given the region’s relatively low emissions footprint, it should be supported to take advantage of these resources without compromising its decarbonization plans. In fact, it could be a more effective way to transition to net zero. The continent also has tremendous potential in renewable energy sources, with renewables like solar, wind, hydropower and geothermal energy capable of supplying over 80% of new power generation capacity.16 However, the development of renewables is constrained in large part by a lack of adequate financing. A dual-track strategy that facilitates the development of fossil fuels coupled with a reinvestment of a share of the proceeds in renewable energy could offer the most promising pathway to net zero. (For a more in-depth discussion of Africa’s energy future and its present energy challenges, see Chapter 3.)

Contracts from mineral and fossil fuel extraction should also be negotiated in fair, progressive, and transparent terms that ensure that the region benefits when prices and profits rise. Many countries have historically seen limited returns from their natural resources due to imbalanced agreements and weak oversight. For example, the region loses between $470 to $730 million annually in corporate tax revenues from profit shifting in the mining sector alone.17

Utilizing sovereign wealth funds

Finally, policymakers should set up sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) to better manage the revenues from natural resources. Currently, sub-Saharan Africa has a few SWFs which hold around $100 billion in assets-under-management.18 However, most resource-intensive countries do not have SWFs. Among the advantages, SWFs help stabilize the local economy from external shocks, such as swings in commodity prices, and help contain currency appreciation that can adversely impact the competitiveness of the broader export sector. When managed well, SWFs turn nonrenewable revenues into long-term financial assets for the benefit of both current and future generations and serve as a source of funding for the broader development agenda.

While African SWFs are primarily invested overseas, evidence suggests investing these resources domestically could help overcome financing constraints, provided these funds are governed transparently and managed professionally.19 Investments should focus on assets with the highest social and financial returns and should be subject to independent oversight and transparency. Investments should also be undertaken in partnership with arm’s-length institutional investors, such as the private sector, pension funds, and development banks.

Conclusion

The deterioration of the global aid framework undoubtedly poses challenges as Africa seeks to sustain progress on its development agenda. It is a reminder that mobilization of domestic resources is now imperative. Yet it also presents an opportunity to look inward and leverage the continent’s inherent comparative advantage. Opportunities to enhance domestic resource mobilization abound, including strengthening tax revenue collection systems, curbing multinational enterprise tax avoidance, and harnessing the potential of SWFs, local pension funds, and national development banks. By seizing these opportunities, African economies can secure a more stable and reliable source of funding for their development agendas.

Toward self-reliance: Financing health beyond aid in Africa

Omer ZangIn 2025, major cuts to external aid for developing countries were announced, especially impacting health systems. Development assistance for health (DAH) provided by the United States, United Kingdom, and France is projected to decline, with overall DAH expected to decrease at least 20% from 2024 levels.20 Over 90% of the projected DAH decline will be through the off-budget channel, currently accounting for two-thirds of health’s foreign financing envelope.21 Funding cuts from donor countries have also forced the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to suspend or wind down health services globally, including in African countries such as Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Mozambique.22

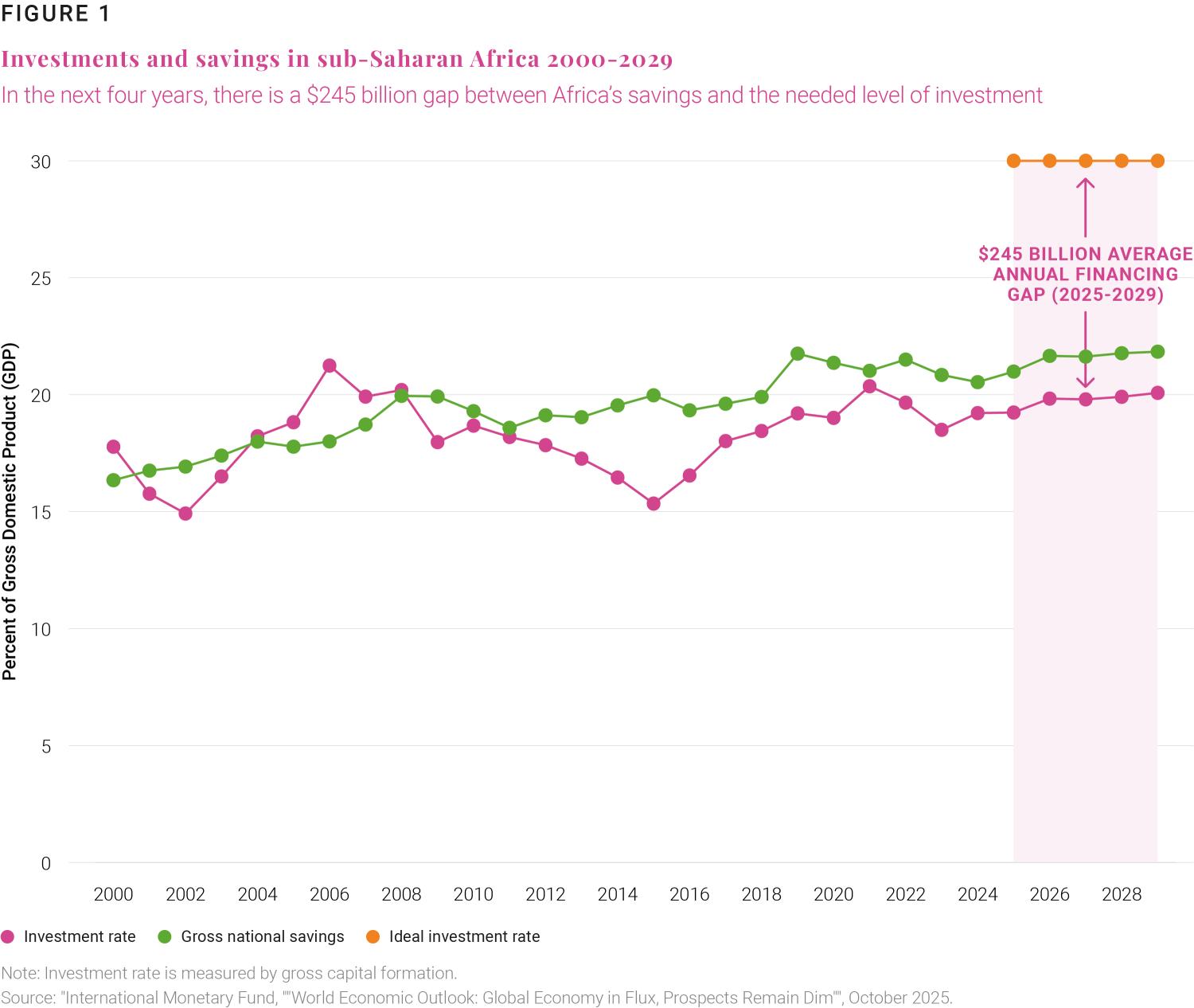

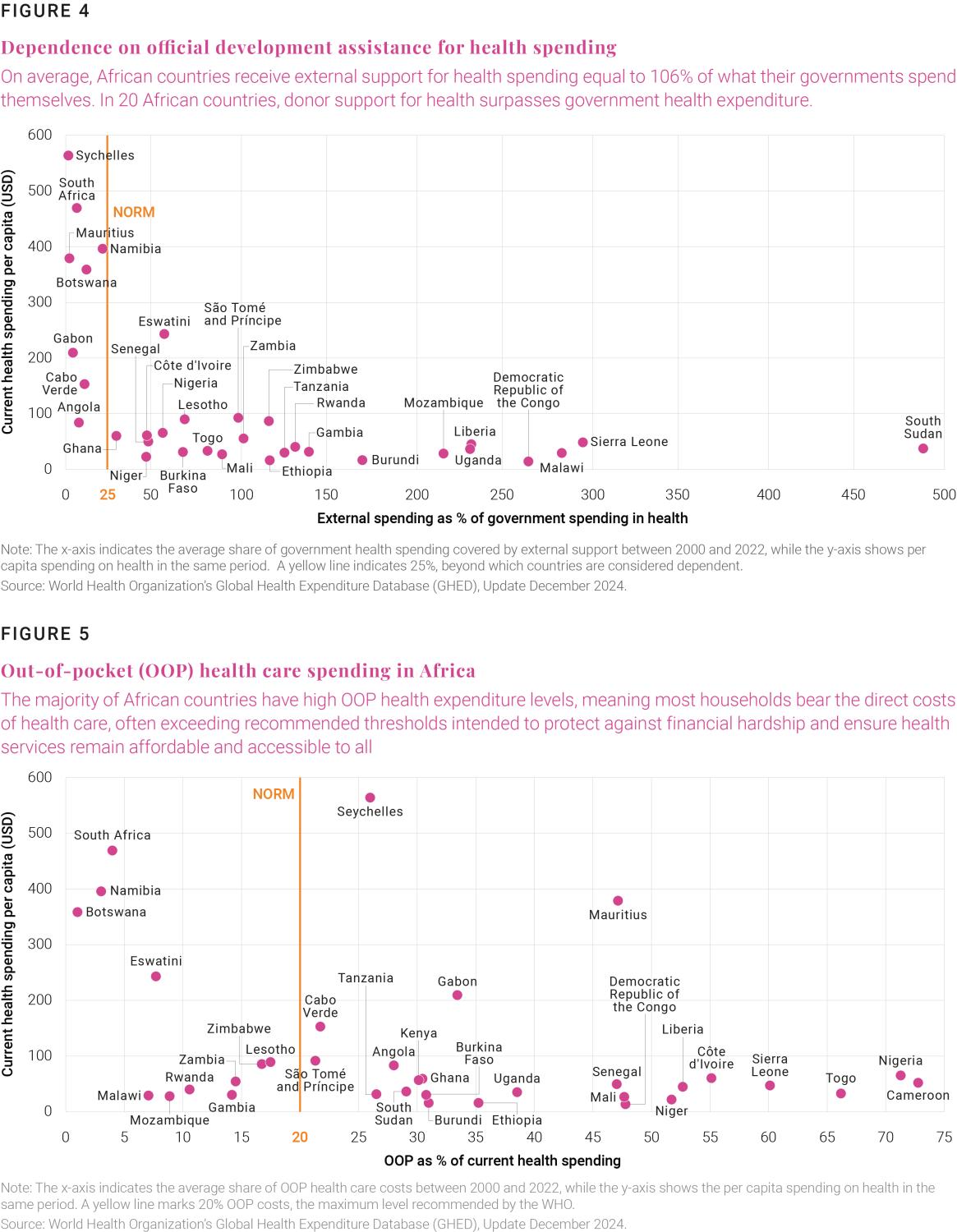

Health systems in low-income countries and those facing fragility, conflict, or violence, still rely heavily on DAH. If we consider countries that rely on DAH for over 25% of public health expenditure to be reliant,23 then about 79% of African countries experience long term reliance on DAH (Figure 4). The impact of the current DAH cuts on each country depends on its donor mix, the extent of the aid reduction, and its proportion allocated to service delivery.

For many African countries, the sudden aid cut is aggravated by the failure to mobilize enough financing for the third Sustainable Development Goal on universal health coverage (UHC).24 Government and donor financing in Africa are already insufficient to cover the costs of basic high priority healthcare, and expanding to UHC goals is predicted to more than double the cost from $36 billion per year to $71 billion in low-income countries.25 Since 2015, progress in UHC pillars—access to and quality of healthcare and financial protection— has either plateaued or declined.26

Compounding this problem is the fact that a decline in DAH may potentially increase out-of-pocket payments (OOP). OOP is a health financing channel that is regressive, discourages service use, and reduces financial protection for low-income and vulnerable groups. Based on the WHO’s recommendation that OOP should account for less than 20% of total health expenditure,27 81% of African countries have excessive OOP (Figure 5).

To craft effective policies for the emerging crisis, countries should first pinpoint weaknesses in their current health financing systems. Health financing systems in many African countries struggle to mobilize sufficient resources, limiting both effective service purchasing and pooling (i.e. the accumulation and management of prepaid funds to enable redistribution and spreading of financial risk28) (Table 1). Government health spending also faces constraints from low revenue and competing fiscal priorities with more urgent issues such as food insecurity, epidemics, and debt distress.29 Given these recurring systemic shortages, African nations should address the impending crisis by optimizing all existing health financing mechanisms— without neglecting any of them (see Table 1).

|

Mobilization |

Pooling |

Purchasing |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Government health spending |

Volume constrained by weak revenue capacity | Underprioritized and poorly executed, undermining pooling | Mostly passive, input-based |

| Compulsory national health insurance | Payroll-based contributions from a narrow formal sector | Weak informal‐sector enforcement, delayed reimbursements | Predominantly passive, Diagnosis- Related Groups /fee-for-service payments |

| Voluntary national health insurance | Mobilizes only limited funds | Small, limited enrollment and adverse selection | Mostly fee-for-service and passive purchasing |

| Foreign in-budget | Volatile, disease-earmarked | Partially pooled on-budget, but still heavily earmarked and fragmented | Input-based and rigid, mostly passive purchasing |

| Foreign off-budget | Can be large, NGO-run | Fragmented, projectized, vertical | Mostly passive purchasing |

| Private health insurance | Voluntary, low coverage, focused on wealthy groups | Small, fragmented pools for wealthier groups | Selective contracting with private providers on fee-for-service, limited spillover |

| Micro health insurance | Tiny, voluntary schemes with low premiums and limited benefits | Small community-based pools | Purchasing basic primary healthcare with limited benefits, weak purchasing leverage |

| Group self-insurance (health) | Optional on health, flat-rate, small community pools | Small and limited cross-subsidization | Passive purchasing with narrow networks and limited bargaining power |

| User fees/out-of-pocket payments | High, regressive, facility-funding | Minimal to no pooling | Used to fund facility drugs/ operations, passive purchasing |

Source: Author’s compilation based on existing evidence and deductions

Strategies to optimize existing health financing mechanisms

First, African governments need to spend better and more on health. In line with the launch of the recent Accra initiative reset for global health governance, the recent decline in donor aid should trigger a sense of self-reliance among African governments. The rest of Africa can learn from the experience of Burkina Faso, which introduced free primary healthcare in 2016, funded by increases to government spending rather than donor reliance.30 Also, this year, Nigeria’s lawmakers proposed a 25% increase in the federal government’s health budget in response to DAH cuts.31 Health administrations in countries should succeed in positioning health spending as a domestic investment that delivers economic growth by building human capital and job creation.32

Advocacy should also aim to direct additional resources toward equitable service of a high priority package that provides the highest value for money and is affordable. There is evidence that low-income countries and many lower middle-income countries can raise their tax-to-GDP by 9 percentage points simply by broadening the tax base and strengthening their tax administration capacity.33

The health sector can also contribute to the tax base through excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks, which aim to discourage consumption and thereby reduce the negative health impacts of these products. Estimates indicate that these “health” taxes could boost government health spending by up to 40%, if the funds are allocated to healthcare.34 In addition, health budget execution can be improved by coordinating health and finance administrations to address bottlenecks, which could avoid losses in public health spending.

Second, there is an urgent need to define “new compacts” for the remaining DAH in African countries. As an example, Ethiopia has initiated compacts for reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health services’ commodities and non-communicable diseases where donor and private sector resources complement domestic financing.35 These new compacts should include health aid for urgent or humanitarian needs.

The new compacts should also foster greater coordination between donor support and national priorities. Donors’ self-alignment to local priorities has not always worked well in the past. Such alignment succeeded only with firm support from local authorities. Foreign in-budget financing is appropriate when well-functioning public finance systems exist and policy options are clearly defined, actionable, and endorsed.

Development assistance for health (DAH) provided by the United States, United Kingdom, and France is projected to decline, with overall DAH expected to decrease at least 20% from 2024 levels.

Foreign off-budget support should ideally be utilized only to pilot or reinforce initiatives with strong evidence of cost-effectiveness, market viability, or fiscal and institutional absorbability. The outlook for pharmaceutical manufacturing in specific African countries or regions is a notable example of such an initiative, given its potential market viability in the private sector, an opportunity that is further strengthened by the continued progress of the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Third, compulsory national health insurance should be implemented after an enforceable plan for integrating the informal sector is in place. A study of six African economies shows that about 37% of informal sector households can save for the long-term and contribute to social protection, while 18% remain vulnerable but are able to make precautionary savings.36 The former category are labeled non-poor informal. Strategies based on innovation and technology are required to expand this group’s engagement with formal prepaid health financing schemes. Also, to expand coverage, compulsory national health insurance and voluntary national health insurance need reliable, long-term subsidies for the poorest.37

Fourth, micro health insurance and self-insurance groups exhibit considerable potential in various contexts and present opportunities for further development. Contributions to micro health insurance or self-insurance groups provide a pool of funds mobilized beyond the amounts that would otherwise be available for health care. The main strengths of micro health insurance and self-insurance groups are the degree of outreach penetration achieved through community participation. They have emerged against the backdrop of severe economic constraints, political instability, and lack of good governance. The full potential of these strategies may therefore be realized if certain design limitations are resolved. Key actions include: (i) gaining a deeper actuarial understanding of these small-scale schemes—especially the self-insurance groups—to inform effective risk transfer or reinsurance strategies, (ii) integrating them with formal financing mechanisms and health service provider networks, and (iii) addressing financial challenges—such as liquidity constraints in rotating savings and credit associations—to incentivize higher participation in health-related risk.

Fifth, the north star for effective public health expenditure should be continuous assessment and enhancement of health service quality across both public and private providers. Quality of health care is essential to a health system’s technical efficiency and crucial for increasing participation in protective health financing schemes. Many countries use performance-based financing to strategically purchase health services, encouraging public spending on defined benefit packages adjusted with a quality index.38

In total, this unforeseen sharp decline in DAH may present an opportunity for Africa to implement critical reforms and foster innovation in protective health financing. Let us not let this “good crisis go to waste.”

Related viewpoints

-

Footnotes

- “Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa” (Washington, International Monetary Fund, 2025).

- Valuation is based on the 2024 Edition of the World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations database.

- “Cuts in official development assistance: OECD projects for 2025 and the near term,” (Paris: OECD, 2025).

- Germany has also implemented significant overseas aid cuts as part of its fiscal tightening, redirecting funds to in-country migrant and humanitarian needs. Similarly, the United Kingdom is reducing ODA to help finance higher defense spending, while France is scaling back amid fiscal pressures and growing domestic political opposition to overseas aid.

- “List of DSAs for PRGT-Eligible Countries, As of September 30, 2025,” (Washington: International Monetary Fund, 2025)

- “International Debt Statistics 2024,” World Bank, accessed December 10, 2025.

- “World Economic Outlook, October 2025,” International Monetary Fund, p. 151, accessed November 18, 2025.

- Brahima S. Coulibaly and Dhruv Ghandi, “Mobilization of tax revenues in Africa: State of play and policy options,” Brookings Institution, October 2018.

- Brahima S. Coulibaly and Dhruv Ghandi, “Mobilization of tax revenues in Africa: State of play and policy options,” Brookings Institution, October 2018.

- “Africa could gain $89 billion annually by curbing illicit financial flows,” UNCTAD, September 28, 2020.

- Estimates are based on the 2024 Edition of the World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations database. Renewable natural capital includes agricultural land, forests, mangroves, marine fish stocks, and hydropower. Nonrenewable natural capital includes oil, natural gas, coal, and metals and minerals. Data is available for 39 countries in sub-Saharan Africa; Cabo Verde, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, South Sudan, and Seychelles did not have available data.

- See Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez et al., “Leveraging US-Africa critical mineral opportunities: Strategies for success,” Brookings Institution, September 29, 2025.

- Wenjie Chen et al., “Harnessing Sub-Saharan Africa’s Critical Mineral Wealth,” International Monetary Fund, April 29, 2024.

- Deloitte, “From Promise to Prosperity: What Will It Take to Unlock Africa’s Clean Energy Abundance?” Forbes, March 25, 2024.

- International Energy Agency, “Africa: Countries and Regions,” accessed November 25, 2025.

- International Energy Agency, Africa Energy Outlook 2022, World Energy Outlook Special Report, Revised May 2023

- Albertin et al., “Tax Avoidance in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Mining Sector,” African and Fiscal Affairs Departments, International Monetary Fund, 2021.

- “Global Sovereign Wealth Fund Tracker,” Global SWF, last updated November 2025.

- Samuel Wills et al., “Sovereign Wealth Funds and Natural Resource Management in Africa,” Journal of African Economies 25, no. 2, 27 (2016): ii3–ii19.

- Angela E Micah et al., “Tracking Development Assistance for Health and for COVID-19: A Review of Development Assistance, Government, out-of-Pocket, and Other Private Spending on Health for 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2050,” The Lancet 398, no. 10308 (2021): 1317–43.

- Anurag Kumar et al., At a Crossroads: Prospects for Government Health Financing Amidst Declining Aid, Government Resources and Projections for Health (GRPH) Series (World Bank Group, 2025), 34–35.

- Allen Maina, “UNHCR: Funding Cuts Threaten the Health of Nearly 13 Million Displaced People,” UNHCR, March 28, 2025.

- Kaci Kennedy McDade et al., “Reducing Kenya’s Health System Dependence on Donors,” Brookings Institution, March 2, 2021.

- United Nations Trade and Development, SDG Investment Trends Monitor, Issue 5 (2024).

- David A Watkins et al., “Resource Requirements for Essential Universal Health Coverage: A Modelling Study Based on Findings from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition,” The Lancet Global Health 8, no. 6 (2020): e835.

- World Health Organization and World Bank, Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2025 Global Monitoring Report (World Health Organization and World Bank Group, 2025).

- World Health Organization et al., eds., The World Health Report: Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage (World Health Organization, 2010).

- Inke Mathauer et al. “Pooling Financial Resources for Universal Health Coverage: Options for Reform.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 98, no. 2, 29 Nov. 2019, pp. 132–139.

- World Bank, Global Economic Prospects: June 2025 (World Bank Group, 2025).

- Frank Bicaba et al., “National User Fee Abolition and Health Insurance Scheme in Burkina Faso: How Can They Be Integrated on the Road to Universal Health Coverage without Increasing Health Inequities?,” Journal of Global Health 10, no. 1 (2020): 010319.

- Dyepkazah Shibayan, “Nigerian Lawmakers Approve $200 Million to Offset Shortfall from US Health Aid Cuts,” AP News, February 14, 2025.

- World Bank, A Fresh Take on Reducing Inequality and Enhancing Mobility in Malaysia (World Bank Group, 2024).

- World Bank and UNESCO, Education Finance Watch 2024 (The World Bank and UNESCO, 2024).

- The Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health, Health Taxes: A Compelling Strategy for the Challenges of Today (2024).

- Solomon Tessema Memirie et al., A New Compact for Financing Health Services in Ethiopia, Policy Paper (Center for Global Development, 2024).

- Melis Guven et al., Social Protection for the Informal Economy: Operational Lessons for Developing Countries in Africa and Beyond (World Bank Group, 2021).

- Watkins et al., “Resource Requirements for Essential Universal Health Coverage.”

- Omer Zang et al., “Impact of Performance Based Financing on Health-Care Quality and Utilization in Urban Areas of Cameroon,” African Health Monitor, no. 20: Special Issue on Universal Health Coverage (October 2015); Yogesh Rajkotia et al., “The Effect of a Performance-Based Financing Program on HIV and Maternal/Child Health Services in Mozambique—an Impact Evaluation,” Health Policy and Planning 32, no. 10 (2017): 1386–96.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).