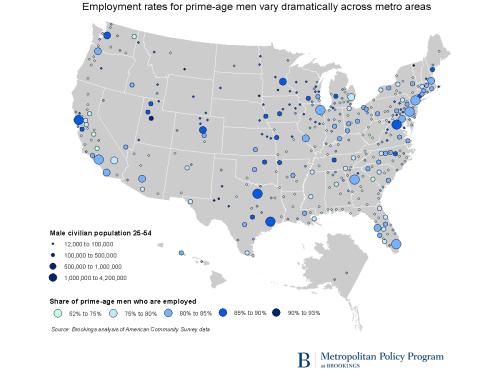

The job market is much better than it was during the worst of Great Recession. The acute pain is past, but chronic problems remain. About 7 million American men between the ages of 25 and 54 – mostly too old to be in school and too young to retire – are neither working nor looking for work; another 2 million are looking for work but haven’t found it. Add them together and more than one in seven men in their prime working years are not working. Fifty years ago, about 5 percent of men between 25 and 54 weren’t working; today, it is around 15 percent. This is bad for them, for their families (if they have any) and for the economy as a whole.

The abrupt onset of the Great Recession and the subsequent sluggish recovery have been our major preoccupation during the Obama years, and rightly so. But we have made substantial steps towards economic health: By the end of 2013, gross product per capita finally rose above pre-recession 2007 peak. In early 2016, unemployment fell below 5 percent. But the presidential campaign – supported by a close scrutiny of the economic data – shows that the U.S. still was far from achieving widely shared prosperity. Despite a recent and welcome surge, the inflation-adjusted income of the median American household ($56,516) was still slightly below the 1999 level. And the fraction of prime-age men without work remains substantially larger than it was before the Great Recession or the previous six decades for which we have comparable government data. (The story for women is a little different: huge numbers of women went to work in large numbers in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, but that trend levelled off in the 1990s. But that’s for another time.)

The fraction of prime-age men without work remains substantially larger than it was before the Great Recession or the previous six decades for which we have comparable government data.

Who are these guys on the sidelines of the economy? They are disproportionately not married; men without work don’t make very attractive spouses. They are disproportionately native born, not immigrants. They are disproportionately African American. And they are far more likely to have gone no further than high school: A prime-age man with only a high school diploma is more than twice as likely to be out of work than one with a four-year college degree.

Why aren’t they working? Some are collecting government disability benefits, but that’s a small share of the total. Some, though not many, are being supported by their wives. Less than a quarter of the men who aren’t even looking for work have a working wife and this fraction has been decreasing for 50 years. Some have prison records, and we know that often is an obstacle to finding work. Some have tried to find jobs, but have given up. And some, to be blunt, aren’t really interested in work.

What are they doing? Jason Furman, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, says time-use studies show that “They’re not spending any more time on child care, not spending any more time on chores. They are spending a lot more time watching TV than men who are in the labor force.”

Why should we care? Some men can afford not to work, and choose not to. That’s great for them. But for most, dropping out of the work force not only means a lack of income and a loss of the dignity that comes with not working, it’s associated with drug use, alcoholism, suicide, and all sorts of other bad outcomes. These men would be better off if they worked, and so would society as a whole. We’d be wasting less human potential. We’d be less vulnerable to the labor shortages that loom as the Baby Boomers retire. And we’d be collecting more tax revenues.

These men would be better off if they worked, and so would society as a whole.

What can the next president do about it? Other advanced economies also have seen a downward trend in the number of prime-age men who are working as the forces of globalization and technology have made the lesser-educated, lesser-skilled less attractive to employers, but none of the other countries have seen a trend as severe are ours, one indication that government policy matters.

A few steps are obvious, though difficult to implement. Government disability programs should be revamped to protect the truly disabled, but provide better incentives to those who can work to do so – perhaps part-time, perhaps with the sort of accommodations prescribed by the Americans with Disabilities Act, perhaps with government wage subsidies. If we found alternatives to prison for those convicted of crimes, we’d have fewer people with prison records that interfere with employment.

Other steps will be even more challenging. Many men simply don’t have the skills or experience to make themselves attractive to employers. Improving our training and job-search programs would help, and a better education system would help prepare more workers for the good 21st century jobs that are available.

Finally, making work more attractive to these men could make a big difference: Stagnant wages, particularly at the lower tiers of the labor market, discourages work. Paying them more–particularly with an expanded earned-income tax credit that gives low-wage workers a cash bonus without boosting employers’ costs–could get at least some of them off the couch.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).