Hillary Clinton has unveiled a plan to improve college access, and few can doubt the urgency of the task. (If you are one of the few, read this by Professor Sean Reardon.) For example, more than 80 percent of new community college students say they want at least a bachelor’s degree but after six years only 15 percent of them have managed to obtain one. Why?

Navigational nightmares and complexity

The process of choosing classes at many community colleges is a nightmare. As Thomas Bailey, Shanna Jaggers, and Davis Jenkins show in their book, Redesigning America’s Community Colleges, navigating through a large number of courses can knock many students off track.

In theory, it sounds good to offer students hundreds of different pathways. But not all students who enter community college—or a four-year college, for that matter—immediately know what they want to study and which set of courses they should take to reach their desired goals, even if they know what these are.

Instead, students at community colleges “develop information [about academic paths] by taking courses almost at random.” Many discover, too late, that “exploratory courses” don’t count towards their major.

Community college students often have to make complex decisions with minimal guidance. This increases the importance of social “know-how,” precisely the type of knowledge that many community college students lack.

Richer kids have fewer options and more guidance

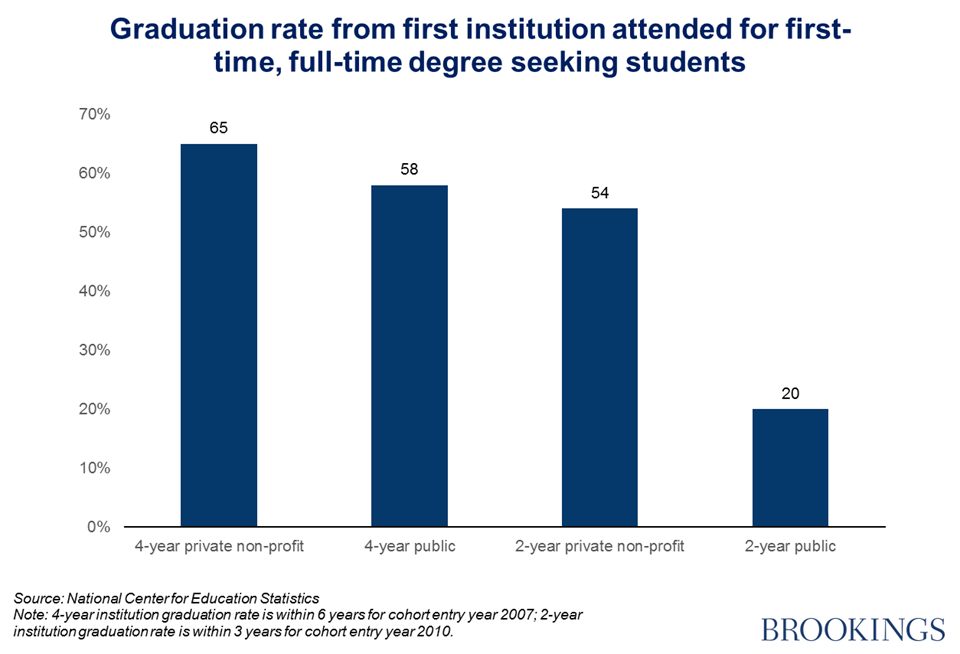

Students at many liberal-arts colleges, meanwhile, enjoy a “guided pathways” approach to navigating higher education. Majors consist of a cohesive set of courses, which build upon one another as students acquire a deeper understanding of the field. It’s easy to track progress along relatively linear course completion and prerequisite paths. Although community colleges offer a somewhat different path from their 4-year counterparts, that shouldn’t be an excuse for giving 2-year students a harder path. Complexity may be one reason completion rates differ so greatly by institutional type:

Here is just one example from the book: In 2011, Harvard offered 43 majors, helped students explore the ones that interested them through core classes, and then helped them chose one through intensive advising. Meanwhile, nearby Bunker Hill Community College had more than 70 degree and certification programs in almost as many academic and applied fields, but limited advisory resources and no required core curriculum.

Consequences of inadequate guidance

As well as worsening drop-out rates, the lack of coherence can hinder students transferring to a four-year institution. Students who can transfer most of their credits (90 percent or more) are 2.5 times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree than students who transfer fewer than half of their credits. But only 58 percent of students fit into the first category, while 15 percent of students virtually had to start over.

There are two kinds of solutions at hand:

- Make community college easier to navigate

Colleges can streamline their course lists into more coherent programs—like majors—that focus on building specific skill sets or preparing students for transfer to 4-year institutions. They could also design “default course progressions” that keep undecided students on track.

Queensborough Community College, for example, now requires full-time students to enroll in one of five “freshmen academies,” ranging from STEM to business and the liberal arts. The common curricula give students a shared academic identity and ready-made peer support groups.

- Turn students into better navigators

Students need help to see the big picture to know where they’re going and how to get there. Most community colleges are able to fund one academic adviser per 800 to 1,200 students; greater state funding and more counselors would give students more face-to-face help.

Needless to say, these reforms are necessary but not sufficient. We also need a radical transformation of post-secondary funding and access. But in the debate over higher education we should remember that details and design matter, too.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Memo to Hillary Clinton: More choice can thwart community college students

August 12, 2015