Just in time for tomorrow’s celebration of Pi Day, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nevada) has given the Senate its own special math problem. Reid filed cloture motions yesterday on 17 nominees to the U.S. District Courts currently pending on the Senate’s Executive Calendar. If Democrats secure sixty votes on each cloture vote, the Senate would be facing 510 (17×30) hours of “post-cloture” debate before reaching final confirmation votes on each of the nominees. For a chamber that often starts the day with Morning Business at 2 pm, this could be a really long month for the most deliberative body in the world. (Fortunately, the Senate doesn’t have much else on its plate this year.)

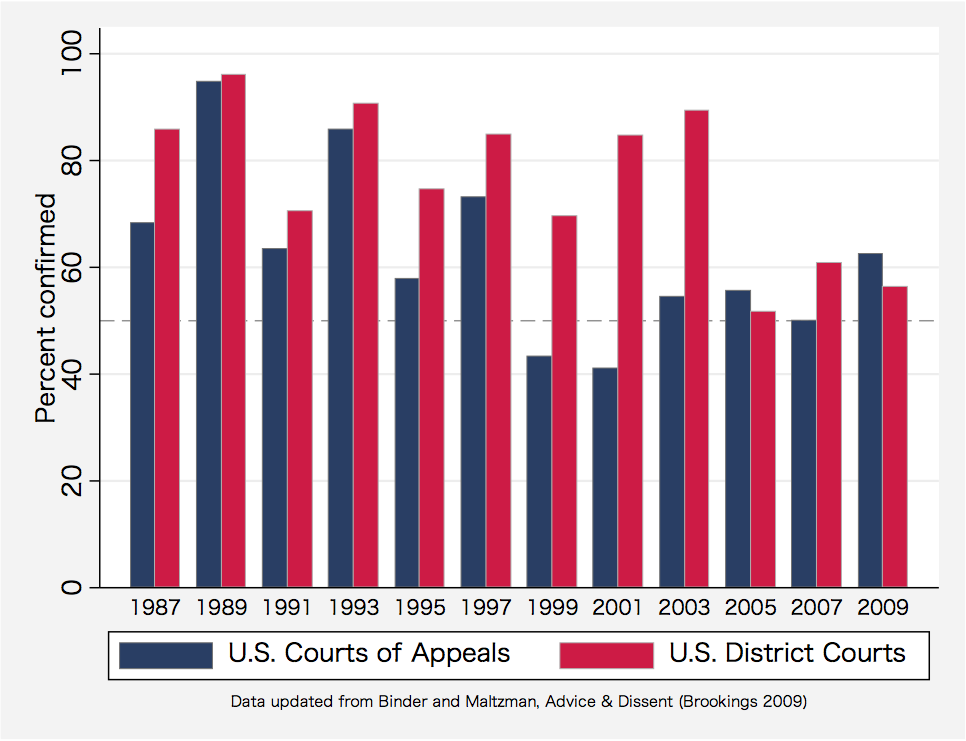

Reid is unlikely to secure sixty votes on each of the nominees, and it’s still possible that Reid and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) reach an agreement to guarantee confirmation votes for a small handful of the pending nominees (although that might require a commitment from the president not to make any more contentious recess appointments). Regardless of the immediate outcome, Reid’s move is noteworthy because it shines a light on a new feature of advice and consent: the spread of partisan conflict to the Senate’s consideration of federal trial court nominees. For most of the Senate’s postwar history, nominees for vacancies on the district court have been immune from the ever-rising partisan heat over advice and consent for judicial nominations. No longer. Some recent Senates have shown only a bare difference in confirmation rates between appellate and trial court nominees:

This sea change has not gone unnoticed in the Senate, as Democrats have bemoaned Republicans’ more aggressive tactics against trial court nominees. In their excellent piece on Obama’s judicial appointments in Judicature last spring, Sheldon Goldman, Elliot Slotnick, and Sara Schiavoni spoke with staff on both sides of the aisle about the increased scrutiny of trial court nominees. One Democratic aide worried that:

They have approached district court nominees with the same exacting inquiry standards that used to be reserved for the Supreme Court and for controversial circuit court nominees, not even all circuit court nominees. But now it extends to every lifetime appointment….It used to be that district court nominees, unless quite extreme, quite unusual, were accorded a different path forward. And now, that’s changed.

Republican staff happily owned up to the new strategy, making plain the policy consequences of giving trial court judges a free pass to the bench:

Each nominee is assessed on his or her own merits regardless of the position in the court system to which they are nominated because this is a lifetime appointment…They [district court judges] deal with serious issues. They deal with Proposition 8, they deal with “don’t ask, don’t tell,” they deal with terrorism cases, health care, and that’s my boss’s view of it…When President Bush was in power and you didn’t want to do this and you just rubber stamped District Court nominees, that’s your problem.

In some ways, the GOP strategy is just tit for tat—retaliating against Democrats for their foot dragging over Bush’s second term trial court nominees that began in 2005. One Republican strategist has also suggested that Obama’s relatively moderate Court of Appeals nominees—and the White House’s sluggishness in sending nominations up to the Senate—leaves relatively few appellate targets for Republicans to oppose. So to some degree, this year’s slowdown on district court nominees—and Reid’s salient push to confirm them—is situational. But we shouldn’t expect the heat over the district courts to go down anytime soon, as both parties now realize the policy implications of every vacant judgeship.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edMath, Senate Style

March 13, 2012