Two challenges uppermost on the agenda of the Biden administration, COVID-19 and climate change, are issues of both domestic and international import. The international elements—help for countries in mitigating the health and economic impact of COVID-19, ensuring access to vaccines, and preventing future pandemics, and help in mitigating and adapting to the impact of climate change—are inherently matters of global development. International progress is imperative for success on these issues domestically. Addressing the international aspects of these transnational crises must be grounded on sophisticated analysis and deployment of resources that strengthen countries long term while reducing the impact of the crises. This requires ensuring that the development mindset is given full consideration as the U.S. develops its strategy and policymaking, but security considerations and diplomatic short-term interests often hold sway, because the short-term political gains are more certain and apparent and the bureaucratic structure works to their advantages.

To elevate the U.S. contribution to global development, the authorities and capabilities of the lead development agency, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), must be strengthened and the agency assigned the prominence that has always been implied by the concept of national security resting on the three-legged stool of defense, diplomacy, and development. Further, USAID must adopt strategies and policies that reflect the priorities of the administration, relevant programs and responsibilities should be assigned to USAID, and the agency personnel system must be rebuilt.

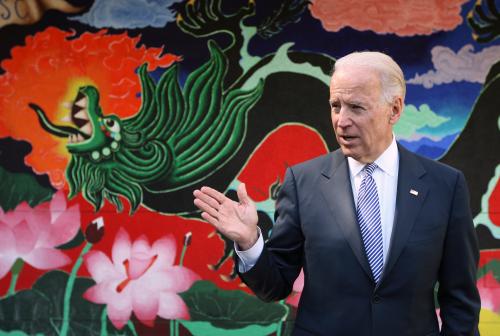

“Give it the resources and support it needs to become once again the world’s premier development organization of the 21st century.”

– Remarks by Vice President Joseph Biden on the 50th anniversary of USAID, November 4, 2011

Challenge

Conceptual and practical. The challenges to assigning development (i.e., USAID) its proper role alongside defense and diplomacy are both conceptual and practical. At the conceptual level is the tension between development being both an element of U.S. foreign policy and national security and a standalone objective. On the one hand, development cooperation and the principal instrument of its implementation—foreign assistance—are used to advance U.S. interests, such as helping to stabilize allies and build market economies.

At the same time, work in development stems not just from its contribution to our national economic and security interests, but from our moral imperative as individuals and as a nation. Public opinion polls consistently demonstrate that the American people are supportive of foreign aid used for public goods such as educating children, meeting health needs, responding to disasters, because it is the right thing to do.

There is no inherent conflict in these two concepts of the role of development cooperation and foreign assistance. Many individuals hold both views. Where the tension comes is in practice—in the tussle of bureaucratic power and control in Washington and in understanding how development best contributes to foreign policy—sometimes in support of a specific foreign policy but more often simply in advancing good development.

In Washington power and prestige, USAID is not in the league of the Department of State and the Department of Defense (in contrast to USAID being held in considerable esteem in many developing countries where it works). The secretary of state is by statute the first member of the cabinet in line of succession to the presidency. The Department of Defense is responsible for what is considered the essential function of government—providing for the common defense—and its budget overwhelms (by a multiple of 14) that of State and USAID.

But prestige and budget size are not the core of the problem. USAID lacks sufficient control and authority over development policy and budgets. Much of its authorities are delegated by the secretary of state. It controls only 60 percent of the foreign assistance budget, with major programs assigned to the departments of State and Treasury and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). Further, a fundamental tension is how diplomats and development experts see their respective roles1, or more precisely that many diplomats fail to understand and respect the unique expertise of the development expert and that development in and of itself advances U.S. interests.

Stripping away USAID’s authorities and role. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy and his advisers, observing the incoherence and dispersion of responsibility for foreign assistance programs, proposed consolidation. The outcome was Congress enacting a new statutory base for foreign assistance, the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, and the president by executive order consolidating foreign assistance programs in a new single agency, USAID.

The subsequent 60-year history has been one of gradual dispersion of responsibility for assistance programs and reduced influence for USAID. It is a complex, iterative story with three principal inflection points.

The first major step in dispersion and loss of control and influence followed the demise of the Soviet Union. The political opening that commenced with Poland and Hungary led the George H.W. Bush administration to propose legislation in 1989 to assist reform in those two countries. Fearful that the Congress would not support foreign aid for what were then still communist countries—Section 620(f) of the Foreign Assistance Act prohibits assistance to communist countries—the administration proposed providing the funding out of domestic accounts for programs to be run by domestic agencies. This evolved into, for example, rather than USAID alone on the front line in those countries, the Labor Department operating free labor programs, the Environmental Protection Agency environmental programs, and Commerce business development programs. Concerned that the spread of assistance across multiple agencies would result in confusion, the Congress wrote into the authorizing legislation, the SEED Act, an assistance coordinator at the Department of State. The FREEDOM Support Act, enacted in 1992 to support the transition of the countries of the former Soviet Union, followed that model of a State Department assistance coordinator. The intent was to provide policy consistency, but the authority of the coordinators to allocate budget among the agencies led to the locus of control centering in the coordinators’ offices.

The second notable moment, a frontal attack on USAID’s independence, came in the 1990s during the Clinton administration with the effort of Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) to reduce government bureaucracy by folding three independent agencies into the Department of State— the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA), and USAID. He succeeded on the first two. The implementing legislation2 that transferred those two agencies into the State Department also affected USAID’s position. It strengthened USAID by establishing it as a statutory independent agency, but weakened it by substituting its line to the president and to the Office of Management and Budget with formal reporting to the secretary of state—maybe not so different on the policy end, as USAID had always received foreign policy guidance from the secretary of state, but significant in the Department of State having a formal review of the USAID budget that too frequently delves into micromanagement.

The third notable dispersion of authority for foreign assistance programs came with three decisions of the George W. Bush administration. Two new assistance programs, the MCC and President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), were established outside of USAID in 2004. The third—stemming from Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s frustration at the inability of the bureaucracy to produce an accurate governmentwide tally of total assistance funding for democracy—was the 2006 establishment at the State Department of the Office of Foreign Assistance (referred to as F), which was joined by removal of responsibility and much of the staffing for policy and budget from USAID to F. Under the initial configuration, the new office was headed by a director, with the rank of undersecretary, who also served as administrator of USAID. This dual hatting worked to the disadvantage of USAID under the first individual to hold the two titles, Randall Tobias, as his approach was more that of the foreign policy perspective of the Department of State, but to its advantage with his successor, Henrietta Fore, who had a greater appreciation of the role of development and spent the majority of her workday at her USAID office. Subsequent administrations ended the dual hatting, with the head of F being a non-Senate confirmed Department of State official. The reach of F has extended from broad review over USAID’s budget to delving into what many development observers view as unproductive, time-consuming oversight of policy, programs, and budget.

Development and USAID were given a more prominent role in the Obama administration, and some of the agency’s responsibilities for policy and budget restored, but basic authorities were not changed.

Limits of historic and existing policies

1) Strategy, policy, priorities

Budgets and structure should follow purpose—fit form to function—which means strategy, policies, and priorities should drive budget and structure. Strategic analysis and frameworks facilitate and make for smarter, more effective policymaking and budgeting.

Strategy. The U.S. government has never had a comprehensive strategy for how to approach development.

The national security agency that represents that model is the Department of Defense. Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act of 1997, the Defense Department has issued five Quadrennial Defense Reviews (renamed National Defense Strategy for the sixth in 2018) that analyze strategic military threats and objectives. The Department of State and USAID attempted to replicate that model in two Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Reviews (QDDR) in 2010 and 2015, but these were restricted to a limited number of policy priorities along with implementation recommendations rather than providing a broad strategy identifying and addressing diplomatic and development challenges and objectives. In 2010, the White House issued a presidential policy determination on global development that provided interagency guidance on key administration development policies and priorities but was not a comprehensive strategy identifying strategic challenges and opportunities.

Policies. Policies are the instruments for ensuring there is coherence in the implementation of a strategy and for articulating administration priorities. Some 30 policies are linked on the USAID registry of policies. Some are a decade or more old and need updating. Others were adopted by the Trump administration and range from the quite good Digital Strategy to the Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Strategy that is a step back and needs to be taken down and rewritten.

Priorities. Every administration has specific priorities and initiatives that define its legacy, typically formed by signature programs—PEPFAR and MCC for the Bush administration; Feed the Future and Power Africa for Obama. Two priorities are already clear for the Biden administration—climate change and responding to COVID-19. Urgent for USAID is developing its contribution to implementing these priorities.

After dismantling the Obama global health security structure, the Trump administration failed to come up with a substitute, but well into its last year it engaged in internal deliberations on a deeply flawed plan that was not implemented. The core of that plan would have shifted critical international health-related responsibility from USAID to a coordinator in the State Department. It would have burdened the State Department with a role for which it has neither the staff expertise nor rigorous processes for operating a multibillion-dollar health program. To put it in charge would add an unproductive bureaucratic overlay on U.S. programs to advance global health security.3 An appropriate model is Feed the Future, with operational management at USAID and a State Department Global Food Security Coordinator bringing diplomatic clout to the program.

President Biden has issued the framework for an international COVID-19 response in National Security Memo #1. The memo determines the United States will rejoin the World Health Organization and support COVAX and the ACT Accelerator, and gives the secretary of state, in collaboration with USAID and other departments and agencies, the charge to develop a governmentwide plan to combat the global COVID-19 pandemic. Interagency coordination will rest with the NSC senior director for global health security and biodefense. This offers USAID the opportunity to present itself as the agency with the experience and expertise in how to assist countries in building their health systems, doing so in a collaborative manner that combines its strengths with the assets of other agencies, civil society, and the private sector.

2) Structure

The structure and responsibilities of government agencies should fit their missions, objectives, and expertise. Determining the appropriate role of USAID requires understanding the shortcomings of the dispersion and nonstrategic mix of responsibilities among multiple agencies and acknowledgement of a few basic premises.

The current fragmentation of responsibility for development cooperation, spread over some 25 government agencies, prevents the U.S. from having coherent policies and programs, resulting in inconsistent and even contradictory policies and uncoordinated and duplicative activities; creates confusion among partners as to what agency to address on a particular issue; deprives the U.S. of presenting a unified position toward partner countries and in international fora; and wastes valuable, scarce government human resources.

The private sector and the military have long understood that smart, timely decisionmaking and accountability are facilitated by definitive lines of authority and empowering those closest to the customer, closest to the action. Fragmentation and overlap prevent clear lines of authority. Coordination among agencies and programs, while at times essential, is a second-best solution to singular lines of responsibility. Further, localization is widely recognized as best practice in development, as programs can be effective only when fit to the local context and engaging local actors. USAID is structured for this reality as it is fundamentally a decentralized agency with considerable authority and expertise resting in country missions, which are most effective when they have the authority to fit their activities to local priorities and adapt them to changing circumstances.

3) Budget

Budget authority. Two problems in the management of the foreign assistance budget in particular hamstring the agency. One is that USAID lacks full authority to manage its budget, yet is held accountable by OMB, the Congress, and the media.

The State Department Office of Foreign Assistance (F)4 was preceded by the Office of Resources, Plans and Policy, which functioned to ensure foreign policy input into relevant elements of the foreign assistance budget, ranging from providing a foreign policy perspective into USAID-managed budgets (development, health, humanitarian, disaster assistance) to more in-depth oversight of State Department security/foreign policy focused funds (ESF or Economic Support Funds, and security assistance). State’s engagement on ESF, driven by foreign policy priorities but some 80 percent implemented by USAID, was focused at the policy level and the amount of assistance allocated to specific countries, not on management and implementation by USAID. That process worked relatively well, ensuring coordination and foreign policy input to the degree appropriate without unnecessary and intrusive duplication of USAID implementation. The approach changed with F. While designed to be a central locus of data on foreign assistance and to coordinate assistance across the government, it has never performed the latter function, in part because other departments such as Defense, Treasury, and Agriculture do not view the State Department as a “neutral arbiter” and refuse to submit to its purview. Its “coordination function” has essentially been limited to going beyond coordination to exercising authority over USAID in what is often unproductive bureaucratic layering.

Budget timeliness. The second budget problem is the lack of timeliness in USAID receiving authority to obligate its budget. As analyzed in a 2018 GAO report, the process for allocating foreign assistance following enactment of the annual State, Foreign Operations appropriations is dysfunctional and a major barrier to the timely allocation of assistance funds. Through the process established pursuant to Section 653(a) of the Foreign Assistance Act process, after enactment, the administration is charged with aligning each budget line item with the appropriated level and securing appropriations committee consent to the alignment. The process took 230 days in 2015 and 80 days in 2016, and in the last two years 265 and 178 days.

Further, the budget planning process starts two to three years before funds are available to be spent. Beyond notional planning, what is the value of setting funding years ahead in rapidly evolving contexts, especially given fragile environments and the frequency of unexpected events like civil conflict and a pandemic?

4) Personnel

USAID will reach the oft-articulated goal of being a premier development agency only to the extent it is staffed with the right personnel who are motivated by the mission, respected by their leaders and peers, and have opportunities for professional development and career advancement.

USAID staffing has declined from some 15,000 in the 1970s to a few thousand today, while the level of funding the agency manages has increased multifold. Many functions that are inherently governmental that should be assigned to full-time government employees are contracted out through costly hiring mechanisms.

In the last several years, USAID staffing has been depleted by a hiring freeze and a historic level of departures. Particularly in the last year, disruptive political leadership has led to a nadir in morale. An effort was initiated in 2008 in the Bush administration by Henrietta Fore to rebuild staffing, with an aspirational goal of doubling the number of foreign service personnel. The effort continued under Raj Shah in the Obama administration. But USAID foreign service personnel fell from a level of around 1,800 in 2016 (1,850 if foreign service limited hires are counted) to some 1,600 in 2019, and civil service personnel hit a low of 1,233. Thanks to increased funding for administrative expenses by and pressure from congressional appropriations committees, USAID targeted on reaching a foreign service complement of 1,725 by the end of fiscal year 2020 (the level funded in the FY 2020 appropriations bill is 1,800) and 1,500 civil servants.

Particularly with the administrator sitting in the National Security Council and the increased demands of interagency meetings, USAID lacks sufficient staff to properly address a broad range of issues, such as climate change and development finance. Further, it lacks the strategy, resources, and “training float” to backfill positions on detail that are needed to invest in the professional development of its personnel. In contrast, the Defense Department comes to the interagency backed by months of planning, deep support teams, and reams of information and data, and on an annual basis has some 10 percent of its personnel in professional development programs.

Political appointees bring fresh ideas and talent, serve to align agency and administration policy, and often provide an agency high-level access to other political appointees, the Congress, and important stakeholders outside government. However, effective management of an agency’s responsibilities depends principally on the deep expertise and experience of career staff. The proportion of political appointments has crept dangerously high in recent years. Section 625 of the Foreign Assistance Act authorizes USAID 110 positions that are “administratively determined” (i.e., political appointments). Recent administrations have utilized this authority to fill approximately 70 positions, principally by individuals with specific technical and policy skills. But the number in the Trump administration reached 109, many without relevant skills and experience and appointed at lower levels that typically are reserved for career professionals, and some with an extreme ideological bent in conflict with USAID culture and policies. A heavy overlay of political appointees stifles career advancement, discouraging talented officers from remaining in public service.

USAID is in the midst of a commendable workforce planning exercise to improve its personnel system. The rework seeks to create a more agile hiring system, including an effort to collapse some 25 cumbersome and costly hiring mechanisms into a few that are more flexible and nimble.5

However, what the agency needs is a fundamental reenvisioning of its personnel system for the 21st century. USAID (like State) has a personnel system modeled on the military—enter the service as a junior officer and work up or out. Is this the relevant model for the 21st century? Long-term career service is important for core USAID managers to develop experience with agency and governmentwide rules, processes, and policies, but USAID is also dependent on staff with highly honed and constantly advancing technical skills that do not require years of service in a bureaucracy; in fact, such skills can become dulled from constant dealing with agency rules and regulation, paperwork, and a focus on program management. If USAID is to perform as a foremost development agency, it needs a more adaptable personnel system with greater ability to bring in experts for periods of two to five years and mid-career skilled technical professionals who can contribute to putting the agency at the forefront of technical knowledge and leadership. Moreover, the agency must have a diverse workforce that represents the face of America. An effective personnel system today must account for millennials having multiple careers; for working spouses; for foreign service families needing a break in Washington or back in their hometown for a few years to support aging parents or children through the period of teenage schooling.

Policy recommendations

The Biden-Harris administration has launched America’s reengagement in the world with an experienced foreign policy team with a history of working together and advancing U.S. interests with vigor but respect for the perspective and interests of other nations and peoples, foundational to securing broad coalitions in support of America’s approach to global challenges. Especially notable for development is the early nomination of the administrator of USAID, Ambassador Samantha Power, bringing to USAID an experienced, respected thought leader with a history of speaking out for what is right in the world and who, formally as a member of the National Security Council and informally as part of the inner national security circle, will bring a strong voice to deliberations not just on development but to related foreign policy issues. It also has made important decisions on the U.S. engaging internationally on climate and COVID-19 response.

To build on this constructive start, there are a number of ways in which the administration can elevate development and move USAID toward the often-articulated goal of being a preeminent development agency.

1) Strategy, policy, and priorities

Strategy

U.S. global development strategy. The administration should work with the Congress to enact legislation to require each administration in its first year to issue a comprehensive U.S. Global Development Strategy6 as to how the U.S. will address the range of global challenges. The strategy would extend across government agencies and be produced through consultation with Congress and civil society and with leadership from the NSC and USAID.

Global development policy. A narrower approach is for the administration, following the example of the Obama administration, to issue a governmentwide development policy covering priorities for both bilateral and multilateral development cooperation. Its development would be led by the NSC and USAID.

USAID mission director strategic role. Under the framework of the development strategy or policy, given the large number of agencies represented at embassies, many engaged in delivering assistance programs, the USAID mission director should be designated the assistance coordinator to the chief of mission and charged with coordinating a country-level strategy that encompasses the development cooperation activities of all U.S. government agencies operating in the country.

Policy

Besides updating old policies, the principle USAID policies and frameworks adopted under the outgoing administration (see Box 1) need to be reviewed to ensure consistency with Biden administration policies and priorities. Several broad policies and frameworks are particularly relevant for the priorities of COVID-19 and climate, the recently released policy on women and gender must be rewritten, and a policy on civil society is needed:

|

Box 1. USAID policies and frameworks adopted 2016-2020 USAID Policy Framework Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Policy Clear Choice |

The Journey to Self-Reliance (J2SR). The J2SR framing is administrator Mark Green’s signature imprint on USAID’s approach to development. It represents an updating and laser focus on USAID’s long-standing work to build local capacity in partner countries in order for them to be able to take charge of their own development and reduce their dependence on foreign assistance. It has become the governing framework for USAID’s operations. The new administration should carefully review the framework to ensure it accounts for its priorities and approach to development.

USAID policy framework. This document is important in serving as an overlay of all policies and should be reviewed to reflect the new administration’s policies and priorities.

Over the horizon. This was a quick exercise in 2020 to create a frame for USAID’s medium- to long-term response to COVID-19. The new administration should mine this effort for lessons learned for how USAID can anticipate and analyze country needs. For example, COVID-19 affects all aspects of development and all countries, not just the 15 identified as priorities.

Clear choice. Likely the most fraught conundrum that the new USAID leadership will have to work through is the agency’s role in the global power struggle with China. Never articulated in an official document, the outgoing USAID leadership did seek to embed an approach in rhetoric and programs, employing the unfortunate term “clear choice,” suggesting countries can work with us or the Chinese, but if the latter then we leave the playing field. In fact, the policy should be for the United States and USAID to step up, not back. The agency needs a policy frame of collaborating with China where possible7 (climate change and humanitarian issues) but offering an alternative to the Chinese approach through its grant assistance model of development based on transparency, localization, and equity for the often forgotten. Further, it can engage with allies in the OECD Development Assistance Committee, World Bank, World Health Organization, and other international institutions to ensure that it is the principles of the Paris Declaration and rigorous analysis that drive official development assistance and use the weight of allied donors and institutions to pressure China into a more constructive use of its deep financial resources.

Gender equality and women’s empowerment policy. USAID has a strong and respected history of advancing women’s empowerment and gender equality. The new policy was rushed through at the end of the Trump administration without due consideration to the considerable input offered from within the agency and from civil society. The policy represents a step back in time, this at a moment when the coronavirus is revealing all too clearly the extent of gender inequality and the social/economic burden on women, including heightened gender-based violence. The policy should be taken down and the prior policy reinstituted while extensive consultations are undertaken on a new policy8.

Civil society. USAID under the Trump administration issued a policy on the private sector and engaged in an internal exercise of how best to frame/conceptualize its relations with governments (Redefining our Relationship). But it did not articulate the agency’s approach to the third principal actor in its development programs—civil society. The Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network (MFAN) issued a set of principles to guide an approach to engaging civil society and held conversations with career USAID staff that can serve as the basis for USAID developing a policy on civil society9.

Priorities

COVID-19. Building on National Security Memo #1, the administration should assign lead responsibility for international assistance policy and management to USAID, based on its capacity for planning and implementation of programs in developing countries to deal with the broad ramifications of COVID-19. USAID, working with the interagency, should develop a plan that deals with the political, economic, and social impact of the pandemic and accounts for the capabilities of other government departments and agencies. For example, in the area of heath it should encompass the narrower but deeper health expertise of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services, and the diplomatic clout of the Department of State.

Climate change. Learning from the foundation laid during the Obama administration and under the overall strategic leadership of Climate Envoy John Kerry, USAID should lead the development, with extensive interagency participation and civil society consultations, of a governmentwide development strategy to deal with mitigation and adaptation to climate change. Like COVID-19, climate change is a global bad that must be addressed through coordinated and consistent domestic and international efforts. Starting points for USAID are the administration’s climate change frame and reviewing all USAID strategies, policies, and frameworks to ensure that they account for climate change and to identify the multiple avenues for U.S. government agencies to address climate and environmental issues.

Sustainable Development Goals. With growing international and domestic commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including in the Democratic Party Platform, the issue for USAID is how to build the SDGs into policies and programs. The SDGs are used by donors in varying ways, from being the frame for a donor’s development strategy, to linking programs and activities to the relevant SDGs, to reporting on impact.

Democracy, human rights, and anti-corruption. Promoting democracy and human rights has long been a central tenet of U.S. foreign policy and development cooperation, unfortunately, undercut by the outgoing administration. After a flowering of democracy in the 1990s, democracy has suffered setbacks the past decade or more. President Biden has called for a Summit of Democracies, and Ambassador Power has specifically highlighted corruption as a priority. USAID will need to determine its role in advancing democracy and human rights and its contribution to the democracy summit. A good starting place is the USAID Strategy on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance. However, that strategy was written in 2013, prior to much of the current backtracking on democracy, closing of space for civil society, spread of nativism and misinformation, explosion of the internet and social media, use of modern technology to track citizen activity, and authoritarian regimes taking advantage of the COVID pandemic. USAID should revisit the strategy to account for current trends and administration priorities of climate and building back from COVID-19. Particularly relevant, USAID brings to the task experience and understanding of how digital both advances and undermines democracy and how corruption weakens democracy, including in serving as a tax on the most vulnerable, deprecating government services, and eroding trust and confidence in government, the bedrock of democracy.

Digital initiative. Under COVID-19 humanity is living and working on-line. That won’t go away when the pandemic is defeated. Digital has the power to create and undermine—to make economic production more efficient and inclusive, but Russia, China, and other autocracies are weaponizing digital tools. The U.S. can launch a major multi-donor public/private global digital initiative10 to bring developing countries into the digital age that will have a trifecta of benefits: development advancement for partner countries; foreign policy/strategic gains as a counter to Chinese aggressiveness on 5G and Russian disinformation; U.S commercial gains. USAID’s new Digital Strategy is a solid foundation on which to build the initiative.

2) Structure

There are several actions the Biden administration can take to reduce the dispersion and assign USAID the appropriate role in advancing U.S. development policies and programs.

Permanent membership of the Administrator of USAID on the National Security Council. Done! This is a significant recognition of the importance the Biden administration is placing on having the development voice at the table when major international issues are considered.

Cabinet status for USAID administrator. Considering that USAID is a major contributor to U.S. national security and economic objectives, assign it the elevated status it deserves and needs both within the interagency and internationally by designating the USAID administrator a Cabinet-level officer. The Biden Cabinet includes Vice President Harris, the secretaries of 15 departments11, and the heads of nine agencies and offices.12 The importance of USAID easily ranks with this group of government leaders.

Consolidation of key functions. Consolidate into USAID key development programs:

- PEPFAR: Has remained mostly an emergency humanitarian program for over a decade and should be transitioned into a development program helping countries to take ownership and develop essential health systems, so should be joined with USAID’s programs to assist countries in building comprehensive healthcare systems; its consolidation into USAID was proposed in the 2011 QDDR.

- MCC: Has made a significant contribution to U.S. development practice, advancing the use of data, rigorous analysis, local ownership and execution of programs, transparency, and accountability. However, as neither the U.S. government nor the development challenges in 2021 are the same as they were at the creation of the MCC, the MCC business model is in need of a refresh. The administration and Congress should review whether to maintain MCC as a separate agency or merge it as a semi-autonomous office within USAID similar to OFDA. Should consolidation be undertaken, close attention should be given to key elements of the MCC model: 1) upfront funding for the life of a country program, allowing investments in infrastructure and long-term systems; 2) accountability measures that place immutable time and budget limits on partner governments that hold them accountable for program delivery and incentivize ownership; and (3) governance criteria that partner countries must satisfy to maintain funding through the course of the program. Moving MCC within USAID and the MCC CEO reporting to the USAID administrator could improve strategic and program coordination of assistance at the global and country levels.

- Other programs: Sort strategically through programs common to both State and USAID (such as humanitarian and refugee assistance, democracy promotion, and human rights), and other agencies, to determine which development-like programs should continue to be managed by one of the other many agencies or transferred to USAID.

Chair of the Development Finance Corporation. The BUILD Act designates the secretary of state as the chair and the administrator of USAID as the vice-chair of the DFC board. As the business of the DFC is directly related to that of USAID and secretaries of state frequently have not attended board meetings, the law should be amended to make the administrator the chair and the other agencies (State, Treasury, and the Trade Representative) represented at the deputy level. Barring that, in the absence of the secretary of state, the USAID administrator should hold the gavel and her responsibilities as vice chair clearly enumerated.

Interagency coordination. Use the authority of section 640(b) of the Foreign Assistance Act to stand up the interagency Development Coordination Committee (DCC) and designate the USAID administrator as the chair.

USAID restructuring—PRP Bureau. Administrator Mark Green led USAID in a thorough review of the agency’s organizational structure. The resulting Transformation plan is a generally well-thought out organizational restructuring that mainly needs a focus on proper implementation. The one outstanding congressional approval of the multiple pieces of the Transformation puzzle as of the end of 2020 was the merger of policy, strategy, and budget into a new Policy, Resources and Performance (PRP) Bureau. The merger is central to the restructuring as it addresses the current disconnect between policy, strategy, and budget. With a sleight of hand in early January, Secretary Pompeo overrode congressional holds on eight congressional notifications, including the hold on the PRP Bureau. Although the agency can now technically move ahead with establishing the new bureau, it should consult with and address the concerns of congressional committees, including by designating the head of the PRP Bureau a Senate-confirmed position and moving expeditiously to staff up the agency to appropriated levels.

3) Budget processes

Several actions can be taken to overcome USAID’s lack of adequate authority for the funds that it administers.

USAID budget authority. For the accounts it manages, USAID should be assigned full budget authority13 and responsibility for the 653(a) process of aligning funding allocations with appropriate levels and for dealing with congressional committees on reprogramming funds.

Scope of F. Reconfiguring the mandate of F is central to giving USAID budget authority. The mandate of F should be designated to: (a) serve as the secretary’s locus of information and advice on all things foreign assistance, specifically what assistance is being deployed on what programs by what agencies; (b) coordinate and oversee assistance programs managed by State; (c) serve as the liaison with USAID’s proposed PRP Bureau to coordinate policy and State Department input into and review of USAID budgets; (d) but not purport to exercise interagency coordination of assistance, as to date that function has never been effectively performed, nor oversight of USAID budget implementation.

4) Personnel

Career appointments. USAID should reserve a significant portion of senior positions for career staff because many positions need the experience and knowledge of career professionals and to provide opportunities for career staff advancement.

Diversity. USAID has a draft policy on diversity, equity, and inclusion that should be finalized and implemented. The policy should address the agency’s need to enhance respect and opportunities for those traditionally marginalized, including women and minorities. It should set forth ambitious goals to increase diversity and inclusion in the civil service and foreign service and an action plan to achieve those goals, with an annual review to measure progress and determine forward action. The plan should cover recruitment, retention, leadership opportunities, and agency culture, and have clear mechanisms for accountability.

Personnel level. Permanent USAID staffing needs to match the level of funding the agency manages and policy and program responsibilities, specifically having permanent staff perform responsibilities that are of an inherently government nature. An assessment in the Obama administration determined that for the foreign service that would be a level of 2,400. Further, USAID has much of the relevant expertise and experience to handle the range of urgent global political/economic development issues, but to meet the increasing demands of interagency processes, especially now that the administrator sits on the National Security Council and with heightened interaction between domestic and international aspects of climate change and COVID-19, it needs additional personnel. A review should be undertaken to assess the level of permanent staffing required for the agency to properly execute its responsibilities.

Foreign Service Nationals. USAID would be strengthened by an enhanced role and career track for Foreign Service Nationals, who provide the bedrock of a USAID mission due to their long-term “memory” of mission activities, knowledge of the country, technical expertise, and ability to function in the local culture. They should have opportunities to serve in senior mission positions and be granted greater decisionmaking authority,14 the need for which is made starkly apparent by their expanded responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Career development. USAID should establish a career-long professional development program, with sufficient staffing levels and a budget that permits a 10 percent “float” of staff in professional development/training programs.

Budgeting for staff. The administration and Congress should review the manner of funding staff through the OE (Operating Expense) budget. USAID’s staffing resources are constrained by being one of the few agencies which funds part of its human resources in a separate OE budget and part from program resources. Recognition needs to be given that much of the agency’s staff is a core part of the development it delivers, not just administrative overhead. The agency should engage OMB and the appropriations committees about the most propitious way to fund human resources.

New personnel system. The administration and Congress should engage the Academy of Public Administration to partner in designing a 21st century personnel system. A starting point for reenvisioning USAID personnel is to consider all options, such as Anne-Marie Slaughter’s concept of a Global Service, removing the distinction between foreign service and civil service and drawing talent from across the government and throughout America.

Conclusion

The saying “culture eats strategy” I would expand to “culture eats strategy and structure.” Central to the goal of elevating development to the status and influence implied in the concept of the 3-Ds and required for USAID to reach its full potential in contributing to U.S. global interests is a change in culture, across the interagency. Bringing about that change will require the leadership of all related departments and agencies articulating and respecting the role of development, ongoing staff training, and extensive Goldwater-Nichols-type programs of staff serving a tour in another agency.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

While the content of this paper is the sole responsibility of the author, he would like to acknowledge the review and comments that strengthened the paper by Susan Fine, Patrick Fine, Larry Nowels, and Tony Pipa.

-

Footnotes

- For more elaboration on this distinction, see George Ingram, “Making U.S. Global Development Structures Fit for Purpose: A 2021 Agenda”. November 2020. Brookings Institution.

- Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act of 1998, found in Division G of the omnibus bill at https://www.congress.gov/105/plaws/publ277/PLAW-105publ277.pdf

- For detailed analysis, see https://thehill.com/opinion/international/512317-usaid-should-lead-global-pandemic-response-in-an-age-of-great-power

- Originally named the Office of Foreign Assistance Resources.

- Adaptive Personnel Project

- In 2017 Senators Todd Young and Jeanne Shaheen introduced S.1228 to require a National Diplomacy and Development Strategy.

- As stated by President Biden on his February 4thaddress at the Department of State – “But we are ready to work with Beijing when it’s in America’s interest to do so.”

- For more detail, see George Ingram and Nora O’Connell, “USAID’s draft policy retrenches on gender equality”. September 10, 2020. Brookings Institution.

- Another relevant document is “Development Assistance Committee Members and Civil Society”.

- Outlined by the author in “The Digital World”, Brookings Institution.

- Includes the Justice Department, led by the Attorney General.

- White House Chief of Staff, the US Ambassador to the United Nations, the Director of National Intelligence, the US Trade Representative, and the heads of the Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Management and Budget, Council of Economic Advisers, Office of Science and Technology Policy, and Small Business Administration.

- Provided in recent appropriations bills but not honored in executive branch execution.

- The difficulty is this would require agreement with the State Department, which views FSNs in a different light; USAID employs local hires with technical skills in positions of professional responsibility.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).