This blog is based on a paper co-authored with Julia Ruiz-Pozuelo of Oxford University and based on a joint survey design and implementation effort with Dr. Mary Penny, director of the Instituto de Investigacion Nutricional in Lima, Peru.

Does hope matter? While we know that individuals and families typically make key decisions based on a desire to achieve a result, we know very little about the role of hope and optimism in determining future behavior or about the links between these beliefs, behaviors, and economic outcomes.

It seems intuitive that attitudes and beliefs determine many behaviors and future choices such as education, occupation, or investments. These attitudes and beliefs also interact with objective factors such as capability and talent, leading to virtuous—or vicious—circles. Yet it is also possible that optimists mis-predict their futures, resulting in frustration and unhappiness in the long run.

What do we know about hope?

Several studies support the first hypothesis. In early work on this topic, I found that higher levels of residual happiness—e.g., the happiness of each individual that was not explained by observable socioeconomic and demographic traits—was correlated with higher levels of income and better health in future periods. Since then, several studies (see here and here), using a range of metrics, from twin and sibling comparisons to lab experiments, have confirmed such a channel, finding again that optimists have better outcomes from the health to the labor market to the social engagement.

In forthcoming work, Kelsey O’Connor and I use panel data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics for the U.S. to study cohorts born between 1935 and 1948—and includes measures of the respondents’ optimism from young adulthood (1962) onward. We find that the respondents with higher levels of optimism were more likely to be alive in 2015, with education being a mediating channel.

Another issue is whether hope mirrors expectations or predictions. We posit that hope is a separate emotion that may operate through independent if related channels. Hope reflects optimism about the future regardless of realistic prospects and/or capabilities. Aspirations, while entailing a clear degree of hope, tend to focus on particular future outcomes and incorporate people’s expectations of what they think they can achieve with effort. Resilience combines hope on the one hand and determination on the other.

Some of my work with Sergio Pinto based on the United States finds that poor blacks, who are objectively more deprived than most other poor groups (in this case whites and Hispanics), are by far the most optimistic of all racial and income groups. While the current levels of life satisfaction of poor blacks fluctuated over time as it did for all groups (from 2008-2015), their high optimism levels did not. We also found that the corresponding desperation, stress, and worry among poor whites linked to their rising rates of premature mortality, due to drug overdose, alcohol poisoning, and suicide.

Some recent experimental studies, based on simple interventions that evoke hope, find significant resulting changes in behavior. One such study finds that the provision of modest assets—such as a cow or other livestock—to poor people in developing countries results in increased work effort. Another study explored the potential of self-affirmation in lessening the mental toll of poverty. The authors asked respondents in U.S. soup kitchens to recall a time they felt positive about themselves, and that in turn resulted in more effort in playing simple games for fun compared to those who did not receive the optimism prompt.

The driving channel in all these cases—as well as in other experiments—seems to be the provision of a hope channel where one previously did not exist. While these studies cannot reveal how long the behavioral changes last, they are, at the very least, suggestive of a virtuous circle.

Raised aspirations without agency, meanwhile, can lead to significant frustration.

Young adults show how hope effects aspirations and investments in the future

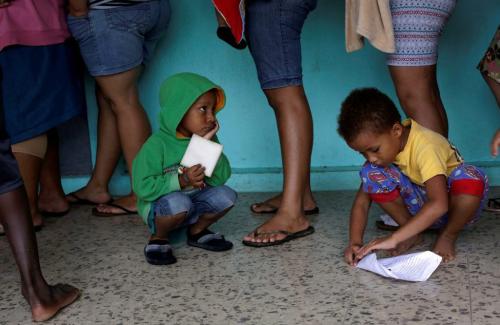

Using a novel survey of poor and near poor urban young adults in Peru, Julia Ruiz-Pozuelo and I attempt to shed light on these questions. We use data on respondent’s aspirations for future education, past shocks and experiences, past and present life satisfaction, as well as other indicators (i.e., self-efficacy, discount rates/impatience, proclivity to risky behaviors) to understand the determinants of optimism. We differentiate between those that relate to objective circumstances (such as higher income or better health) and those that stem from innate character traits and resilience.

In parallel, we exploited the existing data in the Young Lives (YL) survey for Peru, a longitudinal study following two cohorts of children from 2002 to 2014. The YL survey is comprised of five rounds of interviews of children born in the millennial year, their older siblings, and their parents. The Lima segment of the Young Lives survey was conducted in the same neighborhood and by the same survey team as our survey (not coincidentally), and the profiles of the households interviewed are very similar. The round four older cohort in the YL, meanwhile, is the same age (18-19 years old) as our respondents.

This longitudinal study provides us with a benchmark for our survey results and allows us to explore whether optimists typically achieve their aspirations or mispredict their futures. To that end, we examine the earlier round responses to questions about respondents’ future life satisfaction and education aspirations and compare them to their outcomes in these same areas in later rounds. We find a very modest downward adjustment of aspirations, and at the same time a much more robust and positive association between high aspirations in early survey rounds and more positive educational outcomes in the latest round.

Our survey, meanwhile, while not the same respondents in the YL panel (as we could not intervene in the panel), essentially mirrors that population, in terms of the neighborhood, ages of the respondents (the older cohort in the YL), and distribution within the neighborhood. We focused on 18-19 year olds as they are at a point in their lives where they have sufficient education and experience to observe, and yet are at a critical juncture in making key life choices. Our aim with the survey design was to explore the past predictors of aspirations and life satisfaction today, based on battery of questions about past experience, education and health status, relationships with parents, friends, and family, as well as about negative shocks. We also included questions on current and past life satisfaction, internal and external locus of control, self-esteem, discount rates, optimism, and education aspirations. Some of the questions were in the Young Lives survey; many are additional.

We found remarkably high levels of resilience and education aspirations among our survey population. Eighty-eight percent of our young adults aspire to completing college or post-college education. In addition, most of the respondents in this high aspirations category had experienced one or more negative shocks in the past. Respondents in the high aspirations categories are also far less likely to partake in risky behaviors, such as smoking or having unsafe sex. This provides additional evidence suggesting that individuals with high aspirations and/or hope for the future are more likely to invest in those futures as well as to avoid behaviors that are likely to jeopardize their futures.

What we still do not know about hope

There are several questions that we cannot answer, at least not until we repeat our survey next year. The first is whether the high levels of hope and resilience of our respondents are due to innate character traits or to objective circumstances and opportunities. Given the conditions that our respondents grew up and live in, plus the prevalence of negative shocks among the high aspirations group, we believe that there is a strong role for innate traits.

At this point, we do not know whether these high levels of hope and educational aspirations are misguided and will results in frustrations later on. We tested the question to the extent we could in our parallel analysis. We started from previous work based on the YL surveys—from Ethiopia in 2017 and Peru in 2016, 2017, and forthcoming data from Sarah Dickerson. All of this research provides evidence that the life satisfaction/optimism of parents and children in early years are associated with better health and education outcomes (and fewer risky behaviors) in the adolescent years. In this case, we explicitly explored the question whether education aspirations accurately predicted education outcomes in later years.

We do not find much evidence of misprediction. Using past aspirations at different points in time and education level attained in 2013, we find that less than 20 percent of the sample achieved a lower education level than they had hoped for (defined as the “under achievers”). An equal share of the sample, achieved a higher level of education than they first anticipated (defined as the “over-achievers”).

The education aspirations of respondents seem realistic. This may be due to the strong stock that Peruvians place in education—and have historically or due to the wide availability of decent if rather poor quality public education at all levels. It may also associated with growing up at a time in Peru that poverty has been falling markedly, while a nascent—and very visible—lower middle class is emerging, as in many other emerging market economies. Yet the findings also suggest a strong role for resilience and innate optimism, which is pervasive among many poor populations, and seems to be particularly strong in Latin America compared to other regions of similar per capita income levels. While we do not know how lasting that hope channel is, particularly in the face of future shocks or disappointments; we hope to answer that question in future research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Low-income young adults in Peru show the effects of hope on life outcomes

March 16, 2018