There is good reason to be optimistic that al-Qaida’s decline is for real and might even be permanent, argues Daniel Byman. Al-Qaida maintains a low operational pace; it has thin resources, and limited popular support, and indeed, it is regressing on many of its goals. This piece originally appeared on Lawfare. (Read Byman’s second post on this subject.)

Al-Qaida’s power and influence have fallen considerably from its peak in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, but several well-respected analysts suggest the group remains strong and may resurge. My Georgetown colleague Bruce Hoffman argues that as the West focuses on the Islamic State, al-Qaida is rebuilding and plans to assert control after the caliphate’s defeat. Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, a leading al-Qaida scholar at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, concurs by arguing that al-Qaida strategically chose a “more covert and discreet” path, in contrast with the Islamic State—a path that led to its growth in war zones across the Middle East and North Africa. Furthermore, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats’ “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community” argues that “al-Qaida and its affiliates remain a significant CT [counterterrorism] threat overseas as they remain focused on exploiting local and regional conflicts.”

Yet there is also good reason to be optimistic that al-Qaida’s decline is for real and might even be permanent. Al-Qaida maintains a low operational pace; it has thin resources, and limited popular support, and indeed, it is regressing on many of its goals. Rivals like the Islamic State have capitalized on some of its successes, and advancing a movement that other groups have exploited may constitute its greatest achievement.

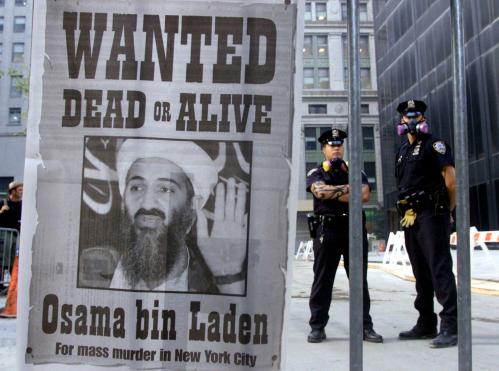

Although terrorism occurs in fits and starts, the numbers and trends regarding attacks in the West are suggestive of al-Qaida’s decline. The al-Qaida core has failed to conduct a successful, spectacular attack in more than 10 years, when its operatives bombed London transportation targets in 2005. Since the death of Osama Bin Laden, the core has had little or no involvement in international terrorist attacks. Successful al-Qaida affiliates rarely attack outside of their theaters of operations, although the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris—linked to al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula—offers an important counterexample as does that organization’s disrupted attacks on civil aviation in the first years of the Obama administration. Most affiliate organizations focus on their local and regional concerns rather than attacking the West.

Often, the number of plots rather than attacks more aptly describes the danger a group poses, yet plots are also an imperfect and potentially misleading indicator. Disrupted plots may indicate a high operational pace, a decline in group capabilities, or improved countermeasures. Al-Qaida still plots to attack the West, but most such efforts depend on amateurs who lack the training of the generation who trained in al-Qaida camps in the 1990s. In addition, as the skills and efforts of security services increase, disrupted plots become more likely, suggesting that the danger posed by the has decreased. In the United States, for example, aggressive law enforcement services now disrupt plots that might never have succeeded in the first place and would certainly have been ignored in the pre-9/11 era.

Evaluating a group’s resources, particularly recruits and money, offers another indicator to determine success. In the 1990s, al-Qaida grew in influence because it doled out cash and training opportunities to an array of groups and operatives. By 2011, volunteers traveling to Pakistan often received little training and paid for their own equipment, leading to considerable resentment. In the post-9/11 era, affiliates in Iraq, the Mahgreb, and elsewhere often send money to the core organization, not the reverse, inverting the core’s power relative to the affiliates. Al-Qaida still draws some recruits, but the Islamic State has long since been the magnet for foreign fighters.

The 9/11 attacks did encourage other jihadists to join al-Qaida, particularly those in Afghanistan and Pakistan who now found themselves on the receiving end of the ferocious U.S. campaign, which did not differentiate between al-Qaida members and those jihadists who traveled in Al-Qaida circles. Yet most jihadist groups were enraged that al-Qaida’s attacks put their organizations at risk, “pinning American targets on their backs,” in the words of al-Qaida analyst Barak Mendelsohn. Important Libyan and Egyptian jihadist groups openly rejected al-Qaida and even turned their backs on violence in general.

Nor does al-Qaida enjoy support among many jihadist clerics and intellectuals who previously championed the group and its causes in the 1990s. Salman al-Auda, the Saudi sheikh whom Bin Laden once praised in the early 1990s and who gained wide popularity for criticizing the Saudi royal family’s ties to the United States, condemned al-Qaida: “My brother Osama, how much blood has been spilt? How many innocent people, children, elderly, and women have been killed … in the name of al-Qaida? Will you be happy to meet God Almighty carrying the burden of these hundreds of thousands or millions on your back?” Dr. Fadl, a leading former Egyptian jihadist, blasted al-Qaida’s interpretation of jihad and claimed the group “committed suicide on 9/11.”

Today, al-Qaida’s successes are based on mindsets, not operations.

Today, al-Qaida’s successes are based on mindsets, not operations. Al-Qaida’s message on the necessity of jihad as a pillar of faith seems a spectacular success; this must be counted as a victory for the group. A range of jihadist groups around the Muslim world as well as the Islamic State have embraced attacks on Western targets, demonstrating this success. Similarly, the idea of global jihad, as opposed to a local focus, is now more mainstream. In the 1990s, some dozens of foreign volunteers would fight in Tajikistan, Algeria, and Chechnya, while Bosnia as the most popular destination attracted several thousand. In stark contrast, in recent times, more than 40,000 foreigners have gone on to fight in Syria and Iraq. In addition, anti-U.S. sentiment in the Middle East is strong, and to some extent, al-Qaida can claim credit for this; its attacks goaded the U.S. into steps like the widely unpopular invasion of Iraq.

Yet why the groups fight differs dramatically. The founder of al-Qaida in Iraq, the predecessor of the Islamic State, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, and the current leader of al-Qaida, Ayman al-Zawahiri, argued over strategy from the start. The current al-Qaida leader claimed that fighting an outside occupying force, such as the United States, was necessary to awaken Sunnis. But Zarqawi’s vision of sectarian war and vicious violence against all enemies proved attractive to more potential fighters rather than al-Qaida’s anti-U.S. focus. Similarly, although anti-U.S. sentiment is strong in the Middle East, most jihadist groups today—including most al-Qaida affiliates—target primarily regional regimes. Al-Qaida historically rejected creating a caliphate, arguing that the time was not right—this idea, however, is one of the Islamic State’s biggest recruiting successes.

Al-Qaida has made only limited progress toward its self-declared goals, and in some cases, has reversed gains. The United States has not fled from the Muslim world with its tail between its legs: with U.S. troops deployed in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and in limited numbers across numerous bases and training missions elsewhere in the Muslim world, the region appears to be even more “occupied.” Long-time foes of al-Qaida and other jihadist groups, like Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak and Libya’s Muammar Gadhafi, have fallen or, are imperiled, as in the case of Syria’s Assad regime. Yet, al-Qaida minimally influenced these changes; and in Egypt, a military coup returned another military strongman in Mubarak’s place.

However, al-Qaida did succeed in fostering a network of jihadists, which allows for many self-sustaining, dangerous dynamics. Initially, al-Qaida-linked recruiters and preachers played an important role by sending individuals to Pakistan and Afghanistan for training and indoctrination. Over time, however, this role evolved into having a range of operatives who preached, helped with travel, and often employed cheap and easy social media techniques. This model has endured. Indeed, the foreign fighter dynamic that al-Qaida helped sponsor proved to be self-sustaining, as Arab Afghans seeded other jihadist groups, which in turn created new foreign fighter flows. As such, the broader movement al-Qaida fostered remains strong. Al-Qaida can be likened to social media companies like Friendster or Myspace that initially succeeded and pioneered many important techniques but eventually saw competitors reap the benefits.

The United States and its allies should consider al-Qaida’s track record as they drive the Islamic State from its territory and diminish its funds and recruits. The successes against al-Qaida are quite real. However, even as al-Qaida declines, the broader movement it fostered remains robust, with other causes and organizations capitalizing on the ideology and networks that the group promulgated.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Judging al-Qaida’s record, Part I: Is the organization in decline?

June 29, 2017